This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 31 no. 1, pp. 46-61

Behind the façade. Exploring the different layers of meaning in an organ performance

Francesca Ajossa, Kurt Bertels

Although the organ frequently occupies a prominent place in an acoustic space, the player of the instrument is often barely visible. In this special concert and listening situation, questions are raised regarding certain (missed) expressive-visual opportunities. In this article, we explore how an analysis of the organist’s score-driven movements and performative experiences can lead to the development of a basic choreographic framework. Olivier Messiaen’s organ piece Subtilité des Corps Glorieux (1939) is our case study. The ultimate goal is to use that framework as a practical tool for interdisciplinary creation and communication.

Een orgel neemt een prominente plaats in in een akoestische ruimte. Toch is de speler van het instrument vaak nauwelijks zichtbaar. Deze bijzondere concert- en luistersituatie bevraagt (gemiste) expressief-visuele mogelijkheden. Dit artikel exploreert hoe een analyse van de op de partituur gebaseerde bewegingen en uitvoeringservaringen van de organist tot de ontwikkeling van een basischoreografisch raamwerk kunnen leiden. Olivier Messiaens orgelstuk Subtilité des Corps Glorieux (1939) is de casestudy. Het ultieme doel is om dat raamwerk te gebruiken als een praktisch instrument voor interdisciplinaire creatie en communicatie.

Setting the scene

Attending an organ recital is a unique experience. Often situated in a church, listeners find themselves surrounded by art and architecture, hearing sounds of a great variety and complexity, unable to discern where exactly they come from and who is producing them. This contrasts with the more usual setting in which performers play on a stage, seen by everyone, often counting on the additional appeal of the visual aspect. In addition to the aesthetic experience, the (im)possibility to see the player in action has been shown to influence the perception of the music’s structural and physical properties, emotional character, and the overall evaluation of the performance.1 From an organist’s perspective, knowing that the audience often cannot see what happens behind the console results in the focus being mainly directed to the technical difficulties of the instrument and the often high complexity of the repertoire, leaving very little space for awareness of the body itself as an expressive instrument.2

In the Organ scene, the issue of visual communication between performer and audience has led to numerous interdisciplinary solutions, showing the urge of organists to extend their expressive horizons. One interesting performance of a selection of Messiaen’s organ music integrated light shows and projected images.3 Dance has also been incorporated in several performances with organ, and has been used as a method to develop the player’s improvisational skills.4 An important observation here is that the interaction between music and its visual counterpart in the above-mentioned performances is often that of a collaboration between two art(ist)s, where a choreographer or visual artist creates new material to accompany the musical one. Another striking element is that amongst all types of visual information, the ones generated by body movements seem to play a crucial role in musical contexts.

The organ with(out) a body

Figure 1a: Salve Regina in its underlying sections.5

The bodily factor and its relation to visual information, musical cognition, and affect, is a well-known phenomenon that has gained prominence in the framework of what is called Embodied Music Cognition. Already in 1872, in The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin describes distinctive body postures and movements in response to emotion-eliciting situations and suggests a powerful body-mind connection both in humans and animals.6 More recent research in music indicates how watching a certain movement can lead to the prediction of thoughts, feelings, and emotions, therefore influencing the perceived expressive meaning of a music performance.7 As far as the association between music and movement is concerned, they both seem to share a unique dynamic structure when communicating emotion. This movement-music coupling seems to be cross-culturally valid and can be seen in a series of human behaviours.8 The correspondence between the deceleration of a runner coming to a stop and a musical rallentando or the similarity between common musical tempi and some biological rhythms, such as the human heartbeat, are convincing examples of that connection. The deep structural links between music and movement have been shown to rely on the mirror neuron system of brain regions that activate when perceiving and performing actions. Moreover, these links might refer to the social and evolutionary function of music as a way of strengthening social bonds between humans.9 It has been argued that awareness of this similarity can represent an important learning point for practising musicians.10

In our artistic attempt to address the issue of visual communication in the context of organ music, the framework of Embodied Music Cognition and its focus on the body as a fundamental mediator between music and mind serves as an inspirational and generative framework. More concretely, we propose the idea of "projection" as a process in which the organ performance is made visible to the audience.11 The concept of "music-projected moving bodies" is introduced, consisting of a dance choreography which is informed by the musical information and the organist’s expressive ideas and body movements. Hence, it represents an attempt to look behind the physical façade of the organ, as well as the metaphorical one represented by the musical score.

About the organ and the body: a case study

This article presents an innovative methodological framework consisting of four forms of analysis: a musical analysis of the score, aiming to give an objective view of the structure and the main inspirational elements in the piece; a self-evaluated vitality analysis indicating the player’s subjective experience while performing; an embodied analysis focusing on the organist’s movements as an unconscious representation of their inner experience; and a Laban Movement Analysis, applied to the organist’s movements in a language that is well known amongst dance practitioners, with the aim of making this information intersubjective. Through this multi-layered analytical approach, we aim to explore what Lucia d’Errico (2019) refers to as “strata of significance (brought about by the musical text) and subjectification (the ‘on-stageness’ of the performer-subject)”.12 Finally, we assemble the results of the analyses in a choreographic base.

In the Organ scene, the issue of visual communication between performer and audience has led to numerous interdisciplinary solutions, showing the urge of organists to extend their expressive horizons.

The choreographic base will be at the centre of the process of creating a choreography, which is one of the final goals of the ongoing PhD Research Project “The Ear as an Eye”, performed in cooperation with the Research Cluster Music & Drama at LUCA School of Arts (Leuven) and the docARTES programme at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent. This is also the context of the collaboration between Francesca Ajossa and Kurt Bertels, from which this article has emerged. The findings from the artistic practice stem from the performance practice of Francesca Ajossa. Kurt Bertels has acted as second author for this article on the methodological framework. Naturally, the various analyses that are part of this text were performed from the first-person perspective of the organist-creator, whose performance is the object of "projection".

The present case study concerns Olivier Messiaen’s organ piece Subtilité des Corps Glorieux, belonging to the organ cycle Les Corps Glorieux (1939). In our example, the role of the organist is expanded to that of ‘creator’, whose job is to collect the various layers of information that already exist within the organ performance and, with the help of the dancer(s), ‘project’ it into visible movement. Les Corps Glorieux was chosen because of its inspiring subject, the biblical “Glorious Bodies” (Phil, 3:21). These are musically described by Messiaen in their physical, bodily characteristics and therefore seemed appropriate to be visually represented by actual bodies on stage.

Figure 1b: Subtilité des Corps Glorieux in its underlying sections.

Score-directed musical analysis

Messiaen’s cycle Les Corps Glorieux (1939) opens with the statement “Leur corps, semé corps animal, ressuscitera corps spirituel. Et ils seront purs comme les anges de Dieu dans le ciel.”13 Despite this cycle being focused on the characteristics of the glorified (resurrected) bodies, Messiaen opens it with a reference to Jesus’ incarnation in Mary’s womb. The Marian antiphon of the Salve Regina, in fact, serves as compositional base for this first movement, which is entirely developed as a monody representing the purity of the Virgin Mary.14 This prayer to the Holy Mary has a fundamental role in the Catholic tradition, being sung in cloisters after the night prayer and just before going to sleep; it can become almost like a mantra, an aspect that is also preserved in Messiaen’s interpretation.15

The original melody of the Marian antiphon is shown in Figure 1a, while Figure 1b presents Messiaen’s elaboration, set in his Second Mode of limited transposition.

This piece is written for an organ with at least three manuals, respectively named Grand Orgue, Positif, and Récit. Each of the keyboards controls a specific set of registers, and therefore organ pipes. The position of these keyboards can change depending on the building style of the instrument: on French romantic/symphonic organs in the style of Cavaillé-Coll (1811-1899), the Grand Orgue is usually the first manual and the Positif the second, whereas on organs with a Rückpositiv (placed at the back of the organist), their position is inverted. The Récit is almost always the third manual, and controls the group of pipes that are placed higher in the organ prospect.

Figure 2: Section A - Messiaen elaborates the original melody, but keeps the tonal centre on the note D, at the end of each small cell, as well as the same melodic shape.

Figure 3: Section B - Similarly to section A, the tonal centre and original contour are preserved.

Figure 4: Section C - In the first part of this section, the tonal centre is shifted to A. Messiaen’s melody is also quite different from the original melody, reaching a higher tension.

Figure 5: Section D - Most of this section has the note A as the tonal centre, and Messiaen’s version is very different to the original one. Here, in correspondence with the most intense part of the text: “Et Iesum, benedictum fructum ventris tui, nobis post hoc exsilium ostende”, an unusual crescendo is prescribed: instead of adding stops of higher octaves, as commonly done in organ literature, the stops to be added make the sound ‘thicker’, building up the tension from ‘within the sound’.

Figure 6: Section E - The difference between these two melodies is evidently very high. Messiaen’s version ends on the note D, in a remainder of the refrain after a very intense beginning.

The structure of this movement is made very clear through a specific pattern: each phrase to be played on the Grand Orgue (as indicated by the letter “G” on the score) is followed by an echo of its last few notes on the Positif (“Pos”). The Récit (“R”), on the other hand, is only used at the very end of the piece as an even softer echo to the Positif. This sort of musical punctuation contributes to a prayerful, mantra-like atmosphere suggested by the contour of the expansion of both melody and rhythm, reflecting the mysticism hidden within the text. The formal structure of the Salve Regina is followed quite closely by Messiaen; however, the “A” phrase is added as a sort of refrain throughout the piece.

The choice of registration suggests an intention to add intensity to this monody: Messiaen prescribes the use of the cornet on each manual which, despite being a single stop, involves multiple pipes for every note being played.16

Figure 7: Section F - The two cells are again similar to each other, they both end in a familiar movement towards the note D.

It is also interesting to notice how Messiaen gradually increases the gap between the Marian and his new melody, as well as using the polarity between the tonal centres of "D" and "A" as an additional way of creating tension. The following figures show this by comparing Messiaen’s piece to the original Salve Regina melody, here written in modern notation for an easier comparison.

This score-based analysis contributes to the choreographic base by providing objective information about the context of the piece and its subdivision into sections, which are also defined by their tonal centre and level of tension. By describing the latter in function of the similarity to the original melody and the composer’s choice of registration, we try to give an objective dimension to what is usually understood as a subjective measure belonging to the sphere of interpretation.

Vitality analysis

The notion of “vitality and vitality contours” was first used and defined by developmental psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Daniel Stern. It refers to “the continual, instant-by-instant shifts in feeling state, resulting in an array of temporal feeling flow patterns” that accompany external movements and behavioural events.17 Pianist and artistic researcher Joost Vanmaele introduces this concept into the discourse of musical analysis by labelling those states of mind as “bio-topics” or “frequently encountered (embodied) states of vitality when performing a specific passage in a piece of music”.18 His idea is that a more systematic analytical interest in these states of vitality can be an interesting addition to the four most common foci of musical analysis: score, auditive signal, musical gestures, and listener’s experience. With this goal, Vanmaele’s work has led to the assembling of a list of seventy bio-topics.19 Having acquired enough familiarity with this list, a bio-topical analysis was carried out from the organist’s perspective, by practising and performing the piece as well as reflecting on the score. This empirical way of analysis seemed in fact the only one possible considering the non-readily observable nature of the bio-topics that come into play in the performance of this piece of music.

The results of this analysis are pictured in Figures 8a and 8b. A bio-topic is mentioned at the point of the score where a new state of vitality was experienced. As indicated by the commas in the musical score, “sense of breathing” is a generally recurring bio-topic in the piece. In order not to interfere with the visualisation of the other text, this is indicated in the score with the letter “B”. The resulting sections can sometimes differ from those that were identified through the musical analysis, both because of their shorter length as well as their starting point, which is usually slightly delayed. This can be attributed to the more continuous and time-based nature of the vitality analysis, contrasting with the ‘above-temporal’ view of the score implied by musical analysis. This difference is intrinsic to the point of view from which one performs these analyses: that of a ‘first-person’ experience (vitality analysis) as opposed to that of an external examiner (musical analysis).

Figure 8a: Vitality analysis in Subtilité des Corps Glorieux.

Figure 8b: Vitality analysis in Subtilité des Corps Glorieux.

As mentioned by Vanmaele, the player’s subjective experience is not amongst the common interests of musical analysis. However, it is arguably a crucial force which makes each performance unique. As such, this kind of analysis represents a valuable contribution to the choreographic base, allowing for the projection, and therefore communication, of the organist’s experience behind the façade.

Embodied analysis

Embodied analysis links directly to the framework of Embodied Cognition and focuses on the organist’s observable movements, rather than the internal developments, relating them to elements of cognition. With that goal in mind, an audio-video recording was made of the performance of Subtilité des Corps Glorieux on the great Marcussen organ (1973) of the Sint-Laurenskerk in Rotterdam.20 This instrument was chosen for being one of the few in the Netherlands on which it is possible to play the whole Messiaen cycle, because of the keyboard and pedalboard compasses and available stops. This instrument contains a Barker machine, a pneumatic system to help overcoming heavy key action; this mechanism was also present in most organs that Messiaen would have been familiar with, with the purpose of making the otherwise heavy mechanics of the organ easier to control.21

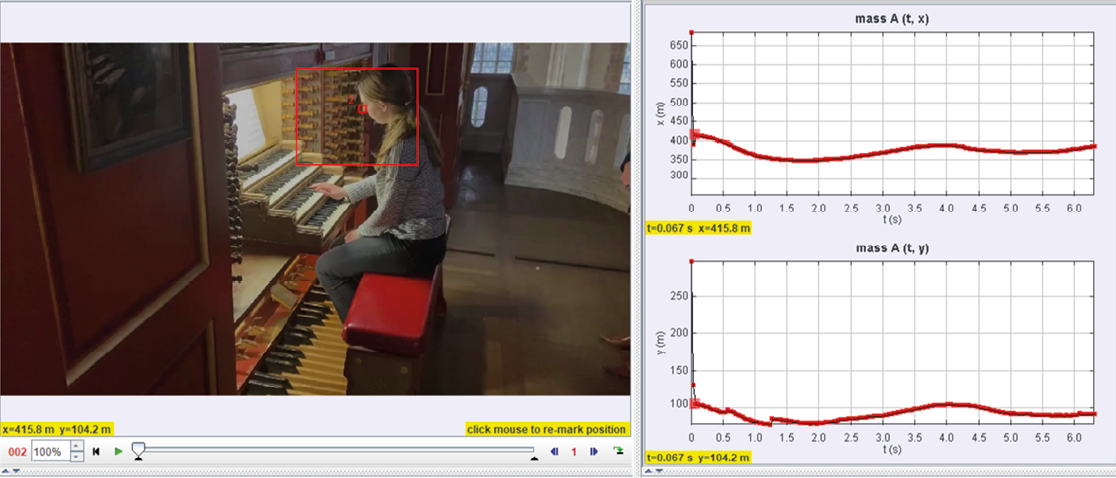

A camera was placed on the left side of the console to capture the full view of the bust, arms and head, where we expect to observe the most expressive movements.22 The video of the performance was analysed using the “Tracker” software. This is a video analysis and modelling tool built on the Open Source Physics (OSP) Java framework which allows for manual and automated object tracking with position, velocity, and acceleration.

A point on the organist’s face was chosen to be tracked, indicated as “A” in Figure 9. The choice for this point was motivated by the fact that the movements of this body part are not related to the sound production, and therefore can be considered as purely ‘expressive’. Moreover, previous literature has shown that the face/upper body are responsible for the biggest and most varied movement during a music performance.23

Figure 9: Analysis view of the Tracker software representing the tracking of the position of point A through time.

Graphs were obtained representing the horizontal and vertical movement of point "A" across time. These are indicated in Figure 9, respectively on the y-axis of Diagram 1 (horizontal) and Diagram 2 (vertical), with "time(s)" being always on the x-axis and the "origin of the axes" corresponding to point "A" in the resting position (sitting position before playing).

The idea behind this type of analysis was to identify abrupt changes in the movements, both in their direction and speed, represented by the steepness of the curve. If movements are seen as a mirror of the players experience of the music, as suggested by the previously mentioned theories on embodied music cognition, a change in movement can be expected to be linked to a change in the experience and therefore identify a new musical section.

Results show that the movement patterns are generally consistent with the sections that can be identified through the musical analysis. Movement starts from a resting position, increases towards the middle of a section with a higher speed and distance from the centre of axes, and then goes back to the initial position towards the end of the section. The same U-shaped pattern is usually repeated in the echoes which, contrary to expectations, sometimes show an even higher intensity in movement. When changing manuals, it is possible that the lifting or lowering of the hands and gaze direction changes the intensity of movement of the head and point "A"; however, the video was recorded with the aim of having as much independence of head and hands as possible. Lastly, there seems to be a movement increase in correspondence with faster notes, as well as often following the direction of the melodic movement.

Figures 10 to 15 represent the instances that differ from the norm, with movement graphs and musical score juxtaposed for a better understanding.

Figure 10: We see here a defined curve with a rising and descending trend starting at 53’ and ending at 65’, in correspondence with the first half of the motif. Hereafter, movement resumes the standard pattern with peaks corresponding to the faster notes, and increases substantially in the echo.

Figure 11: Similarly to the example in Figure 6, the first half of the motif (82’-95’) is characterised by a more static movement around the same position, becoming more varied after 95’.

Figure 12: Between 115’ and 123’, the movement graph shows a big U-shaped curve characterised by an ascending and later descending pattern. A clear drop can be seen in correspondence with the C#, introducing the second half of the motif.

Figure 13: Another big arch can be seen at 180’-188’. As already seen in other examples, movement resumes with the usual trend in the second half of the motif, getting faster in correspondence with faster notes.

Figure 14: The graph shows an increase in movement with every change in registration and dynamics. In the cornet seul section, a big curve can be seen and later on (240’) the movement grows calmer, similar to other sections of the piece.

Figure 15: The first Récit and Positif passages are incorporated in one arch of movement, with an emphasis on the g#-d interval at 286’. The same is repeated, less evidently, in the next two bars.

Similarly to the vitality analysis, the embodied analysis contributes to the choreographic base by shedding light on the player’s subjective experience. Whereas the first type of analysis mainly relies on the player’s conscious, text-based description of their mental states, we believe it is valuable to also provide an embodied, unconscious measure of this complex and ineffable information. Additionally, the graphs resulting from this analysis are a visual tool that can be very useful in interdisciplinary collaborations.

An interim overview

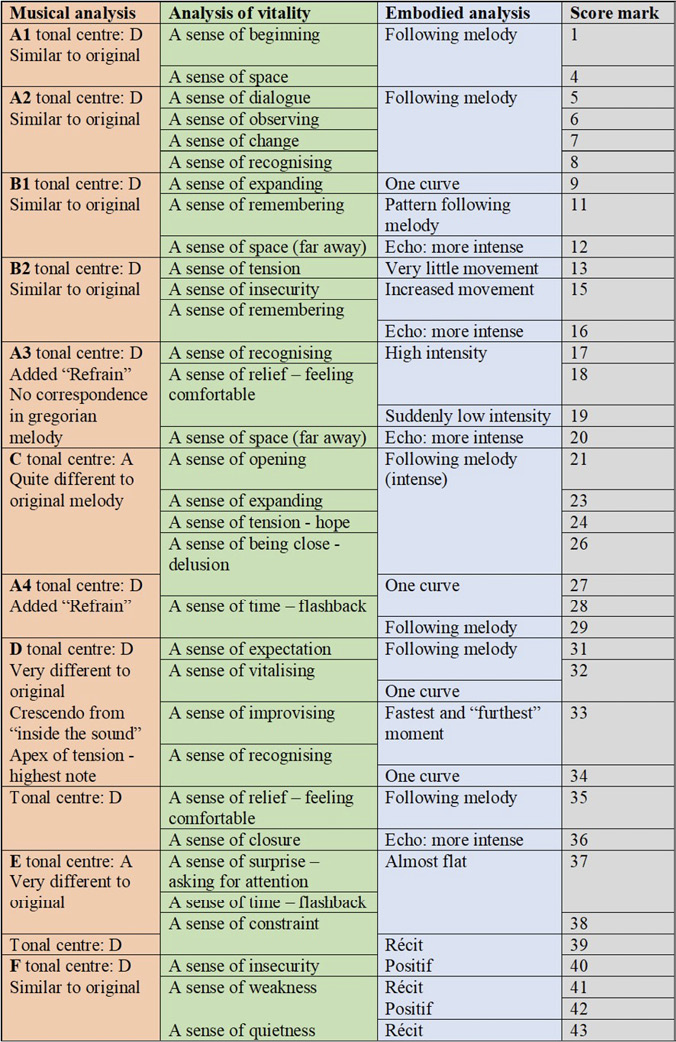

Based on the three foregoing analytical perspectives, we are ready to create an overview with regard to the similarities and differences between the sections identified through different methods of analysis (Figure 16). Comparing different results and gaining an overview of the various sections of the piece functions as a useful tool in terms of study and communication when working on the piece with a bigger group, for example in rehearsal sessions with dancers.

Figure 16: Combined analyses in Subtilité des Corps Glorieux.

Whereas the results of music and vitality analysis are reported entirely, the column related to the embodied analysis mainly indicates whether movement follows the melodic shape, as well as mentioning those behaviours that were previously described as “differing from the norm”. The movement-tracking graphs should still be used next to this scheme, as capturing this aspect in textonly would make it over-complicated.

Because of the irregularity of bars in Messiaen’s score, additional marks were added to better identify the passages of interest (Figure 17).

Figure 17: Score of Subtilité des Corps Glorieux with the addition of a numbered mark for every phrase, indicated by Messiaen’s use of breaths.

Laban analysis

Having conducted the above-mentioned analyses from the organist’s point of view, we felt the urge to add an external analytical perspective. Considering the final aim of this project, it seemed logical to look for this perspective in the dance field; this was also to ensure a higher intersubjectivity of the information that would be contained in the choreographic base and used in the interdisciplinary working sessions.

The 1960s were a period of growing public awareness on how body movements could also be seen as very important carriers of truth and identity, perhaps even more than verbal messages. Therefore, the need to formalise their study became evident.24 Developed by Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) and his pupils, the Laban technique for Movement Analysis (LMA) was one of the first attempts to describe and visualise human movement. Because of its systematicity and intersubjectivity, this method was soon applied in multiple fields, such as dance choreography and criticism, performance scholarship, sports and dance therapy, clinical psychology, as well as in the fields of factory labour and robotics.25

Our methodological framework uses this analysis to describe the organist’s movements in a more accessible language for a broader audience. According to Laban, the dynamic, expressive qualities of movement can be described through the components of “effort” and “shape”.26 The concept of effort can be observed in the tension, release, and phrasing of body movement. It is subsequently divided in four motion factors: weight, time, space, and flow.27

- Weight: ranges from strong to light and can also be described in terms of velocity and acceleration as indications of pressure in the movement.

- Time: defined as how long it takes to perform an action, which can be sudden or sustained. It is therefore related to the speed, tempo changes, and the flow of movements.

- Space: distinguishes whether the trajectory between two points is direct (focused on the goal) or indirect (interacting with other elements of space). It also recognises a contraction or expansion of the limbs in relation to the centre of the body.

- Flow: highlights the amount of tension in movement, that can be bound or free. It looks at the frequency of motion, its fluency, and freedom.

In addition to the already mentioned effort, the component of shape describes their evolution in space according to the basis axes.

Dancer and dance teacher Alessia Crema observed the video and was instructed to analyse movements using Laban Movement Analysis. The scheme in Figure 17 was given to her in order to identify the various sections, but the content about the analysis of vitality and embodied analysis was obscured in order not to influence her judgement. She was also given the possibility to further split a section if she thought it was needed to better describe the movements. Additionally, she was instructed to make additional annotations of distinctive movements that she thought would be interesting to reproduce in the choreography.

Figure 18 shows the combined results of all analyses, indicating the identified sections, musical characteristics of particular interests, states of vitality, movement patterns, Laban categorisation of movement, and other observed movements. This is what we refer to as the “choreographic base”, as it contains all the information that will be used in the process of experimenting with the dancers in the creation of the choreography.

Figure 18: Choreographic base for Subtilité des Corps Glorieux.

Conclusion

This article presents the methodological framework which was developed in order to collect the different layers of information about a musical performance. The final goal is to ‘project’ it into a dance choreography. This creative process is not being discussed in the current article, but will be the topic of following creative and reflective work. Within the analytical phase that we deal with here, our case-study-composition is first analysed both objectively, based on the musical score, as well as subjectively, in terms of states of vitality. Secondly, the player’s movements are visualised graphically and the pattern that emerges is analysed in correspondence with the various musical sections. A third step consists of formally describing these movements through Laban Movement Analysis, ensuring their visualisation within an intersubjective system. Lastly, all the information is structurally compiled in the choreographic base, to be used as a tool for communication and experimentation with other artists.

How can a multifaceted information base connect to other fields of artistic expression and invigorate intense collaborative work and expertise?

The work of analysis and reflection on the musical, expressive, and embodied aspects of a musical performance, in one way or another, is fundamental for any musician who wants to deepen their insight into their artistic work. Musical analysis is a commonly taught subject at music schools and conservatories, but the awareness of one’s subjective experience of the music is often left to the background, even though it can be argued to be the element that distinguishes one’s own performance to the many others of the same piece. The same can be said about the embodied aspects of music: students are often given the instruction to “play as if they were singing”; this could be accompanied by “playing as if they were moving”, as abundant literature shows the benefits and importance of this metaphorical way of thinking. This approach can therefore be used as a way of becoming aware of the ideas and forces that characterise every (musical) performance, fuelling new creations and artistic growth.

In the case of our particular work on Subtilité des Corps Glorieux, analysing the organist’s practice through the lenses of four different types of analysis has had a productive impact on at least three main areas in the performer’s domain. First, it has led the organist to question particular choices that resulted to be performative automatisms. These regarded, for example, slowing down at the beginning and end of a phrase, interpreting an ‘echo’ as softer and accentuating dissonances. Moreover, juxtaposing the graphical representation of the organist’s movements to the passages of the score allowed for an immediate comparison and deeper questioning of the relationship between the two, which wouldn’t be possible with a real-time medium such as video. Secondly, performing this multi-layered analysis was also a useful method for a lively internalisation of the piece. As opposed to the dry repetition of the notes, it represented an opportunity to engage with the musical material through different and stimulating experiential perspectives. Lastly, the possibility to express the player’s subjective experience in terms of states of vitality led to a newly acquired expressive freedom, together with the awareness of “feeling/emotion” as “something that moves”, meaning that it gives an intention to lead the (in this case musical) movement.

Besides the value for one’s own practice as a performer, the choreographic base is first and foremost envisioned as a tool to be used in interdisciplinary collaborations. The description of its role in a creative context deserves a study of its own, but we will briefly point to our first impressions of using the base in the process of creating the ‘music-projected moving bodies’.28

Although both musicians and dancers are used to working with music, it is not surprising that their ways of dealing with this material are very different. In our case, the choreographic base represents a valuable intersubjective tool to ignite our discussions. The aspect of creating the actual movements is, naturally, high on the agenda on the occasion of such an encounter. Various approaches to this goal may be taken, starting either from a desired quality of movement, in our case provided by the Laban analysis, or from a more abstract description of a state, as indicated in the column of the vitality analysis. Lacking an exhaustive written source (external memory) during performance, a dancer needs to develop an excellent scheme of what needs to happen in association with the music. For this goal, the overview of the score-based musical analysis can be of great help as a base to work with. But also the visual representation of the organists’ movements in the graphs of the embodied analysis serves a particular goal: by its visual immediacy, it is the most direct tool in terms of translational capacity.

It is evident that all of these prompts can be used together or separately, and the choice can be also made to create polarising situations that allow for dialogue between music and choreography. The dancers’ perspective vis-à-vis the choreographic base is an important factor that provides additional layers of meaning to reflect on, revealing even more possibilities of interdisciplinary dialogue and reciprocal learning. These relate, for instance, to the interpretation and translation of the states of vitality into physical movement or the way of dealing with the concepts of (musical and physical) space and time.

In conclusion, the use of the choreographic base is a work in progress that has multiple repercussions and fields of impact, both in the domain of the organist individually, and in the collaborative process with a dancer. We attribute this creative ongoing potential mainly to the various objective and subjective lenses that are combined in the analytical complex, thereby allowing for a diversity in the information that becomes available for subsequent intersubjective action. Our first experience in the domain of interdisciplinary relations between musician and dancer is certainly an exciting stimulus for further and wider investigations in the interdisciplinary field. How can a multifaceted information base connect to other fields of artistic expression and invigorate intense collaborative work and expertise? With this initial attempt to map the organist’s performance in the choreographic base, we hope to have shown the potential of this tool as a stepstone to bring the ephemeral and abstract components of music performance "beyond the façade."

+++

Francesca Ajossa

is an organist and artistic researcher based in the Netherlands. She is currently a doctoral student at LUCA School of Arts and the KU Leuven (Belgium), as well as being enrolled in the docARTES programme at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent. Her research interests include interdisciplinary creations, embodiment, performance practice, and audience experience. She also has an international career as a performer, with repertoire ranging from early to contemporary music.

Kurt Bertels

is a classical saxophonist and postdoctoral researcher (LUCA School of Arts/Royal Conservatoire Antwerp/Koninklijk Conservatorium Brussel). He performs both in Belgium and abroad as soloist and as a member of various ensembles. He has published a monograph, Een ongehoord geluid (2020), on the history and performance practice of the nineteenth-century saxophone. As an editor, he has published Paul Gilson (1865-1942). Een Brusselse componist van de wereld (ASP Editions 2023). In 2024, he will launch The Legacy of Elise Hall: Contemporary Perspectives on Gender and the Saxophone (Leuven University Press). He is a member of the Young Academy of Belgium (Flanders).

Footnotes

-

Schutz, Michael, and Scott Lipscomb. “Hearing gestures, seeing music: Vision influences Perceived tone duration.” Perception, vol. 36, no. 6, 2007, pp. 888-97;

Chapados, Catherine, and Daniel J. Levitin. “Cross-modal interactions in the experience of musical performances: Physiological correlates.” Cognition, vol. 108, no. 3, 2008, pp. 639-51;

Vines, Bradley W., et al. “Music to my eyes: Cross-modal interactions in the perception of emotions in musical performance.” Cognition, vol. 118, no. 2, 2011, pp. 157-70;

Morrison, Steven, and Jeremiah Selvey. “The effect of conductor expressivity on choral ensemble evaluation.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, vol. 199, 2014, pp. 7-18. ↩ - Although some concert halls and cathedrals do have movable consoles, the vast majority of organ concerts, especially in the Netherlands/Belgium, are played on historical organs being played from a mechanical console placed in an organ loft. ↩

- Dreaming like Messiaen. Concert. Performance by Geerten van de Wetering (organist) and Marcel Wierckx (audiovisual artist), 15 Dec. 2022, Kloosterkerk, Den Haag. ↩

-

Lekkerkerker, Jakob. “To be a Dancer at the Organ: Creating Vibrant Music, based on Rhythmical and Bodily Impulses.” Orgelpark Research Reports, vol. 3, 2020, pp. 281-94;

Hamlet. Concert. Performance by Hans Davidsson (organist), Henrik Jandorf (actor), Jonatan Davidsson, Lucie Rákosniková, David Lagerqvist (dancers), Stayce Camparo, Jonatan Gabriel Davidsson (choreography), and Anders Bergsten (light), 14 Oct. 2018, Tyska Kyrkan, Göteborg;

The Four Seasons. Performance by Hans Davidsson (organ), Stayce Camparo, Jonathan and Gabriel Davidsson (dancers), Joel Speerstra (reader), and Joakim Brink (lighting design), Göteborg International Organ Academy 2012, Örgryte Nya Kyrkan. gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/31853;

Tango & Organ. Concert. Performance by Aart Bergwerff (organ), 14 May 2019, Moskou in Theater, Moscow;

Simeon ten Holt - Canto Ostinato, A Spiritual Concert: East meets West. Performance by Aart Bergwerff (organ), 2 Oct. 2011, Utrecht Dom. ↩ - “Salve Regina II (LH554).” Liturgisk Ressursbank, liturgi.info/Salve_ReginaII%28LH554%29. ↩

- Darwin, Charles, and Phillip Prodger. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. Oxford University Press, 1998. ↩

- Sedlmeier, Peter, Oliver Weigelt, and Eva Walther. “Music is in the muscle: How embodied cognition may influence music preferences.” Music Perception, vol. 28, no. 3, 2011, pp. 297-306. ↩

- Sievers, Beau, et al. “Music and movement share a dynamic structure that supports universal expressions of emotion.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 1, 2013, pp. 70-75. ↩

-

Molnar-Szakacs, Istvan, and Katie Overy. “Music and mirror neurons: from motion to ‘e’motion.” Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, vol. 1, no. 3, 2006, pp. 235-41;

Phillips-Silver, Jessica, and Peter E. Keller. “Searching for roots of entrainment and joint action in early musical interactions.” Frontiers in human neuroscience, vol. 6, 2012, p. 26. ↩ -

Friberg, Anders, and Johan Sundberg. “Does music performance allude to locomotion? A model of final ritardandi derived from measurements of stopping runners.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 105, no. 3, 1999, pp. 1469-84;

Moelents, Dirk, and Leon Van Noorden. “Resonance in the perception of musical pulse.” Journal of New Music Research, vol. 28, no. 1, 1999, pp. 43-66. ↩ -

Godøy, Rolf Inge. Sound-action awareness in music. Oxford University Press, 2011;

Leman, Marc, and Pieter-Jan Maes. “The role of embodiment in the perception of music.” Empirical Musicology Review, vol. 9, no. 3-4, 2014, pp. 236-46. ↩ - D’Errico, Lucia. “For a Future of the Face: Faciality and Performance.” Conference Abstracts for 12th Annual Deleuze & Guattari Studies Conference. Royal Holloway, University of London, 8-10 July 2019, p. 78. ↩

- I Corinthians XV, 44; Matthew, XXII, 3. “Our body is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body. And it is like the angels of God in heaven.” (own translation). Messiaen, Olivier. Les Corps Glorieux. Alphonse Leduc, 1939. ↩

- Leduc, Alphonse. Technique de mon langage musical: texte avec exemples musicaux par Olivier Messiaen. Editions Leduc, 1944, p. 31. ↩

- Ingram, Sonja Stafford. The polyphonic Salve Regina, 1425-1550. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1973. ↩

- The stop of the cornet is made of a combination of pipes of 8', 4', 2 2⁄3', 2', 1 3⁄5', respectively playing the fundamental, octave, 12th, 15th, and 17th. ↩

- Stern, Daniel N. “Vitality contours: The temporal contour of feelings as a basic unit for constructing the infant’s social experience.” Early social cognition: Understanding others in the first months of life, ed. by Philippe Rochat, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc, 1999, pp. 67-80. ↩

- Vanmaele, Joost. The informed performer: towards a bio-culturally informed performers’ practice. 2017. Leiden University, PhD dissertation. ↩

- The list was assembled as a result of the discussion of various repertoires with piano-students of the Stedelijk Conservatorium Brugge (BE). The term “bio-topic” is used in contrast to Ratner’s “Topical analysis” (1980), with the goal to replace its intrinsically cultural “topics”, restricted to 18th-century music, with more fundamental and universal “bio-topics” representing performer’s experience and vitality whilst playing a piece. A few examples of bio-topics are: a sense of beginning/end/change; a sense of power/weakness; a sense of walking/dancing/vitalizing; a sense of elegance/simplicity/energy. ↩

- See the full video at: youtu.be/0oeL1HvMvZo. ↩

- The “Barker lever” is a pneumatic system which employs the wind pressure of the organ to inflate small bellows called “pneumatics” to overcome the resistance of the pallets (valves) in the organ’s wind-chest. This lever allowed for the development of larger, more powerful organs still responsive to the human hand. ↩

-

Camurri, Antonio, Ingrid Lagerlöf, and Gualtiero Volpe. “Recognizing emotion from dance movement: comparison of spectator recognition and automated techniques.” International Journal of Human-computer Studies, vol. 59, no. 1-2, 2003, pp. 213-25;

Dahl, Sofia, and Anders Friberg. “Visual perception of expressiveness in musicians’ body movements.” Music Perception, vol. 24, no. 5, 2007, pp. 433-54. ↩ - Castellano, Ginevra, Marcello Mortillaro, Antonio Camurri, Gualtiero Volpe, and Klaus Scherer. “Automated Analysis of Body Movement in Emotionally Expressive Piano Performances.” Music Perception, vol. 26, 2008, pp. 103-19. ↩

- Lausberg, Hedda. Understanding body movement. Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2013. ↩

-

Payne, Helen. “The psycho-neurology of embodiment with examples from authentic Movement and Laban movement analysis.” American Journal of Dance Therapy, vol. 39, 2017, pp. 163-78;

Davis, Stanley M. Managing corporate culture. HarperCollins Publishers, 1984;

Rett, Jorg, and Jorge Dias. “Human-robot interface with anticipatory characteristics based on Laban Movement Analysis and Bayesian models.” 2007 IEEE 10th international conference on rehabilitation robotics. IEEE, 2007. ↩ - Laban, Rudolf, and Lisa Ullman, editors. The mastery of movement. McDonald and Edwards, 1960. ↩

- Maletic, Vera. Body-space-expression: The development of Rudolf Laban’s movement and dance concepts. De Gruyter academic publishing, 2011. ↩

- Some video material of our current working sessions can be found here: youtu.be/E4mCH3agJu8. ↩