This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 32 no. 1, pp. 4-11

The gaze and the edge

Ira A. Goryainova

Continuing her previous text on writing and filming through the body, Ira A. Goryainova explores the dynamic between the politics of the gaze and the power of the image. In proposing to consider the gaze as a border experience, she tries to grope and comprehend that border. In this auto-fictional essay, she turns herself into an object and revisits some of the seminal theoretical works, weaving a fabric in which transgressive behaviour, eugenics, medical imaging and Western art history intertwine with her own practice.

In het verlengde van haar eerdere tekst over schrijven en filmen via het lichaam, onderzoekt Ira A. Goryainova de dynamiek tussen de politiek van de blik en de macht van het beeld. Ze stelt voor om de blik te beschouwen als een grenservaring en probeert die grens te betasten en te begrijpen. In dit autofictionele essay verandert ze zichzelf in een object en herbekijkt ze enkele van de belangrijkste theoretische werken, waarbij ze een weefsel spint waarin transgressief gedrag, eugenetica, medische beeldvorming en de westerse kunstgeschiedenis verweven zijn met haar eigen praktijk.

1.

Transgressive behaviour

“Transgressive” means going beyond or violating a boundary or limit, especially in a social, moral, or legal context. “Transgressive” situates itself on or near a border. A margin. Transgressing is marginal. Ad marginem. Transgressing beyond borders. Over the edge. An edge is a border. The word is mostly used in the context of primary and secondary schools to indicate certain rebellious types of children’s behaviour, and also in the arts, film production and cultural sector in general. Thus it turns out that transgressive behaviour is widespread among children and artists. Among the former, it belongs to a phase in identity formation and in the exploration of norms that are not clearly defined. For the latter it functions as part of seeking new ways to navigate through and beyond already fossilized norms. Ground-breaking. In contrast to their actions, a child and an artist are like each other, and we would like to accept their transgressive behaviour were it not for the fact that this adjective is mostly associated with its counterpart meaning, one charged with connotations of a sexual nature.

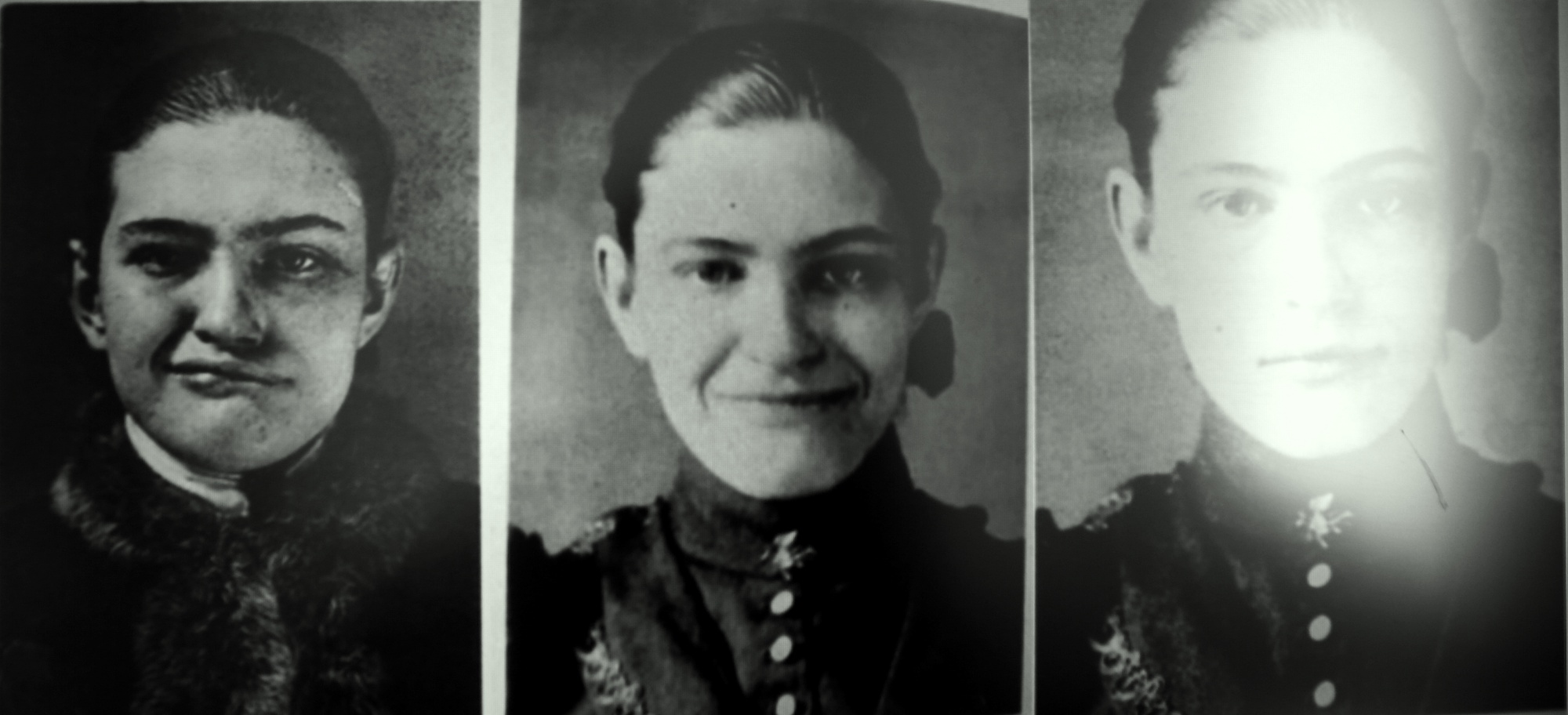

Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière, screen photo of a still from Regarding Faustine (2024), a film by Ira A. Goryainova

Example 1:

A pupil in class 4B sends a picture of female genitals to another pupil during a class. That evening at mealtime the parents of the two children receive a message in their school diary: “disrupting the class, showing transgressive behaviour.”

Because of the children’s transgressive behaviour, the parents now suddenly feel marginal. They don’t have to feel that way, but the power of the word is all-consuming. The children and their parents have met each other at the edges (of society).

It is difficult, however, to define the limits of the word ‘transgressive’ in relation to cultural and artistic activities. It serves as a basis for discussion, disagreement, manipulation. Art functions at an unconscious level, in a space full of darkness, smells and intuitions, which means that we can only feel our way through it.

Example 2:

In a country with a far from progressive agenda when it comes to women’s rights, a director (X) invites a non-professional actress (Y) to drink spirits during a filming expedition. X is making his fiction film in a ‘documentary’ style and often films his actors without prior warning. X and Y had agreed that Y could stop the filming at any moment to “step out of the game.” During a lengthy interrogation scene, an NKVD1 agent (played by another non-professional actor who was a former KGB agent in real life) forces a heavily drunken Y to perform sex with a wine bottle. X calls his work ‘art.’ He invites neo-Nazis to participate in another scene and films them in the same ‘documentary’ style, that is, he doesn’t direct them. In the presence of other non-professional actors, the neo-Nazis slaughter a pig after painting the Star of David on it. The director considers the presence of the neo-Nazis on the set as “relevant and correct in a period of growing nationalism around the world.”

Those on the border find the ground falling from under their feet.

Yet the main bulk of the professional community (both in the country with a far from progressive agenda, as well as their Western colleagues) remains blind to such transgressive behaviour, for if there is no civil party, there is no border and therefore no transgression of it.

2.

Love of the new2

I am leafing through a book by Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909) – an Italian eugenicist and phrenologist who taught that criminality is inheritable and easily distinguishable by the shape of one’s skull, among other things. Black hard cover, thin pages, dense text, extremely small line spacing: a typical Russian edition of scientific literature from the early 2000s. The editor’s preface to the book was therefore written more than half a century after the Holocaust. It is replete with the pronoun ‘we’ in relation to the noun ‘lawyers,’ followed by the verb ‘know.’ Echoing the author, the editor states that “the anomaly of the soul, called crime, must translate itself into an anomaly of the body” and so, he draws a line between us and them. Them, the criminals marked by ugliness, versus us, the lawyers, the society, and the knowing men, who are supposedly marked by handsomeness. In the space of just one page, the editor places himself into a very interesting position: he attempts to draw a line but does not manage to withdraw his subjective self from the object of his knowledge. He writes that Cesare Lombroso demonstrated

The extent of our guilt before the criminal, he showed us that we have not only left the criminal cold, hungry, dark and weak, but that we have distorted his human image, shrunk his skull, loosened his nerves, desiccated his muscles, maimed his bones, we have wrinkled his face, ruined his sight, destroyed his hearing, his sense of smell and touch, we have killed his imagination, in one word, we have removed him bodily from human nature, we have emasculated him and cannot expect him to have human feelings, thoughts and actions.3

This is a good illustration of circulating around a border. Transgressing it. Of distancing oneself from the other, yet not being willing to give away the power of making the other the other. A sweet dichotomy. But most of all, it is a good illustration of how the gaze functions: taking into consideration ‘objective’ visual data, it exercises power over the seen to such an extent that the gaze seemingly creates what it sees – something new, something that wasn’t there before: an Untermensch. The gaze thinks to be informed by what it sees, but is instead itself informing what it sees, constructing it and creating a knowledge.

3.

Gaze

The sensation of my gaze materializes the moment someone draws my attention to my own gaze. Why are you looking at me so viciously? A soft gaze, languid eyes, purple mist on the cheeks. Wandering. Piercing. Contemptuous gaze. Instantly, an embodied geometry rolls out: for each eye, about 55° up, 60° down, 90° outwards and 60° inwards – that is the human field of view. The muscles around my eyeballs tense and frame my vision. In total, it covers approximately 180°, but to see three-dimensionally, in colour and intently, much less. 130° for a wandering gaze. 60° for a vicious gaze. 0° for an inward look. I establish an imaginary line between my eyes and the subject I behold. The retina absorbs the light and sends visual pigments into my central nervous system: I get a grip on what is happening in front of me. And therefore, I grasp it. Like hooking a fish onto the fishing line of my illuminating eye. I am the predator, eating alive the subject I behold.

Georges Bataille said that the mouth is the beginning or the prow of an animal. It is its most living part and therefore the most terrifying for other animals.4 A human, he said, does not have as simple an architecture as animals do. It is impossible to say where a human begins. At the top of the skull? The forehead? The eyes? He pondered:

The violent meaning of the mouth is conserved in a latent state: it suddenly regains the upper hand with a literally cannibalistic expression such as mouth of fire, applied to the cannons men employ to kill each other. And on important occasions human life is still bestially concentrated in the mouth: fury makes men grind their teeth, terror and atrocious suffering transform the mouth into the organ of rending screams.5

Thus, in order to frighten, one has to open one’s devouring mouth. But what if we are mute?

I begin when an imaginary line is established between me and the one who draws my attention. I began when I drew an imaginary line between me and the other in my reflection, connecting it with the flesh of my own body. In order to become one, one needs another. My gaze constitutes me: in becoming oneself, the eyes are the object we see most of all, the gaze is an act we perform most often. As Nabokov would have put it: I am eye.6 The etymology of the word gaze comes from the old Gothic 𐌿𐍃𐌲𐌰𐍃𐌾𐌰𐌽 – usgasjan, "to terrify".

Screen photo of a still from Bile (2019), a film by Ira A. Goryainova.

I am trying a gaze on. What does one or another gaze feel like? There is a question of temporality in it: is it a fleeting event or something which sticks to one’s personality? If I look at the Russian translation of the word gaze (взгляд – vzglyad), I am stuck in another dichotomy. Vzglyad is a fleeting moment,7 but at the same time, it refers to someone’s point of view. I have a different point of view on these matters.

The gaze constitutes the subject one beholds. And so, it works in both directions. I am trying a male gaze on. As a child I was always impressed by the fact that animals at once know where to look. They look at our eyes, just as we look at each other’s eyes when encountering, talking, saying goodbye. When I notice a cat casting a vicious eye at the top of my head, I know it wants to attack me. Does it consider the top of my head to be my beginning, my prow, something to be afraid of? Sometimes when encountering men’s eyes, I discover I have a few other beginnings: breasts, legs. And a tail? Perhaps the tail then is the end of me.

4.

Male gaze

Laura Mulvey described the male gaze as a dichotomy:8 it functions somewhere on the border between scopophilia – the visual sexual pleasure of watching another person – and identification – the pleasure of seeing recognizable things and therefore identifying with what he is watching. In the dominant cultural industry, such as commercial cinema, a female character is objectified and sexualized, not granted any meaning or narrative function: soft gaze, languid eyes, purple mist on the cheeks. Below are the breasts, the skin, the thighs, and the slightly rounded abdomen – falling out like tomatoes, eggs, chicken fillets and other groceries from an overflowing supermarket bag. Locks of her hair are hanging over this wealth, unobtrusively hindering, promising something more. His gaze is piercing: Why does she need all this abundance? Give it to me instead. He has not yet decided whether to hate, or to hook it on his fishing line, to eat it alive. As Mulvey said, the female character stops the development of the narrative, pauses the passage of filmic time. The only reason to do so is to get that sexual pleasure from watching her objectivized body.

In total, my gaze covers approximately 180°, but to see three-dimensionally, in colour and intently, much less. 130° for a wandering gaze. 60° for a vicious gaze. 0° for an inward look.

I am sitting in a café. There’s something socialist about its name; however, it contrasts with the general atmosphere of individualism, of having a different view on these matters. It seems that one of the visitors, at whom I look with a certain tinge of voyeurism and identification, comes here every day. She, like me, stares longingly at her computer screen, though she is never distracted into contemplating the other visitors. Yesterday she looked at me too, and we pretended not to notice each other. However, a smile hung in the air, slowly melting away, like the friendly mouth of a Cheshire cat. Today, an elderly man in a hoodie sitting next to me – the second table from the window, with his back to the wall – in response to my smile offered to buy me a coffee. I declined. I looked up at the paper mural the size of the wall behind the man. Seven women reminiscent of hetaeras9 are towering on it, frozen in a dance. They are surrounded by thick exotic greenery and wear blue and pink dresses, ineptly covering their abundances, or rather unobtrusively hindering them, promising something more. Their eyes are covered by a white veil – an emptiness, as if the artist had run out of paint, leaving the canvas unfilled. They cannot look back. Women – zombies, devoid of gaze. There is a kind of a ribbon in their hands, which they are passing to each other, not knowing what to do with it. Or perhaps it is the imaginary line of their gaze, a homeless fishing line. In the distance behind them, there is some kind of ancient Roman construction, an arch of triumph. Bright orange rays radiate from it as if from a divine sun. I take a picture of the mural and drop it into a picture search, but find nothing which tells me about the image or its motif. However, the artificial intelligence of the search engine offers me a textual reference: Possible related search: fictional character.

Photo of the mural at Maison du People café in Brussels. Photo by Ira A. Goryainova.

A female fictional character, according to Mulvey, is essentially passive. Her only raison d’être is to be looked at. Opposite to that is the active male character, who is gazing driven by fear and anxiety, for each woman is castrated and her wound is bleeding.10 Terrified by such a state of affairs, men tend to create two types of narratives: in one they turn the female character into a mere object of beholding and desire, depriving her of any other meaning; in the other they create a mysterious woman, a femme fatale. A woman to study, unravel, tame and control.

5.

Medical gaze

Albert Londe created a twelve-eyed camera in 1893. He used it to capture epileptic seizures in motion. Londe was one of the medical photographers who made history with his portraits of female patients at the Salpêtrière Psychiatric Hospital in Paris. One can see Londe as a follower of Muybridge.11 The difference between the two, apart from their slightly asynchronous location on the axis of time, is only in their relationships to the image: Muybridge was hired to portray possessions of a certain man in power (a typical subject of Western fine art: women and other possessions) who wanted to have a crystal-clear portrait of his horse at full speed; Londe combined tradition with professional passion – portraits of women became medical.

Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière, screen photo of a still from Regarding Faustine (2024), a film by Ira A. Goryainova

I am trying on a medical gaze. It is my favourite; you could have guessed by now. Medical gaze is described as an act of objectivization of a patient by a physician.12 It is the opposite of a body without organs – organs without a body. A dehumanized body. A framed body, placed on a computer screen connected to an MRI scanner, on the surface of the black emulsion film of a roentgenogram, in the space of an operating room, in the frame of a hospital window, constrained by the hand of the psychiatrist holding it, fringed by the rectangular edges of a steel autopsy table. I bring to the surface the disease I seek and project it virtually onto the organs extracted from a corpse. I scrutinize, demystify, tame and control. I gain knowledge. Nothing can escape my penetrating gaze of about 60°.

A woman from Salpêtrière. Pictures of you are spread across books, journals, and the internet. I have found these and I do not know what is the order of their appearance on the axis of time: from left to the right? Or from right to the left? It is the question of consent, though, that interests me here the most. Not only were you reduced to an object in the process of transformation of a neurological ailment into a mental one, you were also enclosed into the frame of this image without permission – mental patients are declared incapacitated, unable to make decisions or give consent.

And I am replaying this image again, too.

Did I leave you cold, hungry, dark, and weak, distort you from your human image, shrink your skull, loosen your nerves, desiccate your muscles, maim your bones? Did I remove you bodily from human nature? And still, I love you.

I am filming the computer screen of a medical imaging scientific researcher. Layer by layer gradually overflowing one into another, he demonstrates to me what one’s skull, head muscles, ligaments, circulatory system – a visceral striptease rewind – look like through 3D imaging based on an MRI scan. Picturesque. As we are reaching the skin layer, I recognize a real face with its features: the shape of the closed eyes, size of the nose, lips, weakness, and sadness. Throughout evolution, our brains have developed a separate group of neurons that respond differently to faces than to any other objects. Assessing emotional expressions plays a crucial role here. Meanwhile, the researcher informs me that an MRI of the entire head is technically possible only if the person is dead – this man has committed suicide. His face imprints onto my retina, and I can no longer separate the previous abstraction of medical visualization from the ‘real’ person I just saw.13 The abyss of this human body is gazing back at me, as I am empathizing and identifying with a corpse.

6.

Arms of the Venus de Milo

Climbing out of the bathtub, I let my gaze linger on the narrow upright mirror. Dust, some splashing. Softly plain tiles on the walls. The window. Everything is streaming with someone’s pleasant domestic routine. Someone’s – that’s because when we moved here five years ago, it was exactly the bathroom that struck me the most with its homeliness, it felt like people lived here and that this house was built and arranged for life, not for profit. My body in the reflection of the mirror is like the Venus de Milo in reverse. She lacks arms, while I have got not only arms, but also a house filled with some substantial existence, almost palpable – as if one could touch it with hands – as well as dust, splashes, plumbing and other shortcomings, making the house somehow alive, speaking to me.

I look down at my stomach – scars are shredding it. One along my lower abdomen, horizontal, crooked, ugly, still tinted with a dash of colour ‘healing of the flesh.’ On the left side it is thin, almost imperceptible-white, on the right, thickened, swollen, the abdominal muscle is somewhat creepy healing there. Everything seems to be in place, but it is exactly this place that brings me back to the Venus de Milo. Four smaller scars are scattered a little higher – they have healed and are hardly visible anymore. Just a memory of how P. saw my stomach and clenched in pain, reaching out his hands towards it, makes the dissipated scars more tangible. He mumbled a few words of compassion and tenderness, then frowned even more, and said slightly in horror that it was as if he was looking at a crime scene. Tears seemed to show in the corners of his eyes, like when on a bad weather day, it suddenly feels like a cold drop has just fallen on my shoulder and I look at the sky wondering whether it just seemed or is it time to go inside anyway.

Screen photo of Venus de Milo sculpture. Photo by Ira A. Goryainova.

A man’s hands reaching out to a woman’s rounded belly is a powerful image, deeply rooted in the human mind, as natural and essentialist as a swelling chestnut bud. It cannot be confused with anything, just as the Venus de Milo and her ‘armlessness’ can’t be confused with anything. Or am I exaggerating here? Perhaps this tableau is not older than cinema? Time after time being handed out to us like a pamphlet on a street corner near a subway, by a man who is not really keen on the content of what he distributes, for he just needs an income? But it doesn’t really matter. Two weeks earlier, I had been operated (a common surgical procedure) on a gynaecological chair – the nurses and the surgeon had no idea that one of my last thoughts before falling into the unconsciousness of anaesthesia was the memory of filming a scene in a morgue, where students performed laparoscopy on female cadavers in gynaecological chairs, legs up and apart, just like mine. A surgical robot’s pitchfork was thrust into my air-inflated belly, the surgeon went into a state of flux, like a painter tweaking the beauty or harmony of a composition, adding somewhere, but mostly removing the unnecessary, the excessive, the exaggerated; he did his thing, after which my body was taken to a waking room. And there I was in the bathroom, a few weeks later, P.’s hands reaching towards my rounded, rugged belly, while outside the window a May rain might have been dripping, moistening the delicate green of the buds that had just blossomed.

7.

Gap

The absence of the arms of the Venus de Milo is what fascinates us the most, I once read. Something that is missing, something that is not there any more. A lack, or a gap to be filled with a story, an imagination. Something to bridge over. But the image of Venus’s armlessness clung to the mind like a tick, dissolved throughout the body, became natural and nestled itself as a visual bug somewhere at a nerve plexus. Her armlessness has long been invisible, there is no longer a gap in it, but some dull understanding that it should be like this. That a fresh May raindrop will always fall on a blossoming bud. To get rid of the automatic perception of something, it is necessary to defamiliarize it, to make it alien. Like stripping a word of its meaning by repeating it without stopping until it becomes new, a signifier without signified, as if a child would hear it for the first time, not knowing what it means, but noticing that it sounds somehow funny and tickles the ear – that is the aim.

Venus a hundred times.

Peering at her torso, I strangely go through a process of alienation too: suddenly, her arms are no longer a fascination, but only stumps, helplessly sticking out in opposite directions. An arm chopped up like a pork knuckle on the left side, a rotting edge of a shoulder on the right. One of the nipples and both earlobes are missing. Chipped piece of chin, abrasion on the right eyebrow. Venus the Mutilated. Traces of time have mottled the surface of her torso, reminiscent of stretch marks on living skin. Besides, on the photograph I’m studying, part of her chin has a strange warm tint, as if some other substance had been glued to her face, to embellish and tidy it up. And now suddenly I feel: between Venus and me stands her alienated image. Not thousands of years, not the distance between the Louvre and me, not the speed of the Internet, the myriad of reproductions or the beauty contests, but only a thin blade of her image, like a cut in the fabric of perception – the border. In the wound formed by this cut a question is looming: Where in fact are her arms? And why do I identify with a lack? Passivity. A pure object with no subjective agency, with no capacity for handling, while powerful figures were often reduced to a hand: the hand of God, or that of the artist, the gestures of a speaker, or dexterity of a surgeon. I linger my gaze on the narrow upright mirror – dust, some splashing, softly plain tiles. In the negative of the Venus de Milo image – my arms and my hands. Venus a hundred times. I grab a camera and fix the wholeness of my body, the gaze and the border between them.

+++

Ira A. Goryainova

is a film director, audiovisual artist, and researcher based in Brussels. The relationship between body, camera, screen, and spectator is her main area of interest, which she explores in essay- and montage-films, video installations, writing and performances. Thematically her focus is on the body under extreme conditions – such as illness, death, and suffering – and how they can be read as political metaphors while still conveying explicit bodily, non-narrative meanings.

Footnotes

- NKVD – The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs – the punitive body of Soviet power, responsible for many millions of repressed and executed people, later transformed into the KGB. ↩

- This is the title of a chapter from the book by Cesare Lombroso, in which he describes how love of the new is a pathology, inherent to anarchists and other “criminals with altruistic tendencies.” Cesare Lombroso, Crime, The latest advances in the science of criminality, Anarchists, Moscow, INFRA-M, 2004. ↩

- Ibid., p. VII. ↩

- Georges Bataille, “La bouche,” in Documents, Jean-Michel Place Editions, Paris, 1991, pp. 299-300. The “Critical Dictionary” entry, “La Bouche” (The Mouth), by Georges Bataille, was published in the journal Documents c. 1930. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Nabokov’s novel about a man committing suicide and therefore existing in an out-of-body state – it is unclear whether he ‘really’ died or not – is called The Eye, for its phonetical resemblance with the word "I". Furthermore, the protagonist obtains an identity only through other protagonists, when he is being mirrored in them, in how he is being seen through their eyes – an identity which is a new one for every other protagonist: a lover, a thief, a spy, a paranoiac, etc. ↩

- In Russian, another word is used to indicate the gaze as seen in critical, social, feminist and film theories – ‘optics’. ↩

- The term "male gaze" was proposed by Laura Mulvey in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (Screen 16, 6-18), in which she sheds light on how most Hollywood productions at that time unconsciously reflected the power relations of Western society. Although Mulvey’s text, from a contemporary perspective, can be considered as ignoring multitudes of various spectatorship regimes, the male gaze does not seem to falter or have disappeared from popular culture and media, also when taking into consideration different parts of the world. ↩

- Hetaeras were educated courtesans in Ancient Greece, providing more than just physical companionship for influential men. ↩

- Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. ↩

- Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) is a pivotal figure in the history of cinema due to his groundbreaking work in motion photography, which laid the foundation for the development of moving pictures. His most famous series involved photographing a galloping horse using multiple cameras, which demonstrated that all four of a horse’s hooves leave the ground simultaneously. This project, known as “The Horse in Motion,” was a critical step in understanding and recording motion. ↩

- The term was coined by Michel Foucault in The birth of the clinic: an archaeology of medical perception. London: Tavistock, 1973. ↩

- According to the modern General Data Protection Regulation legislation, so very different from the era of the Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière, it is forbidden to use a person’s personal data without their granted prior consent, and even abstract medical imaging scans are forbidden without permission of the person portrayed. Unless the images are anonymized. An MRI image is considered anonymized if no names or special case diseases whatsoever are visible on it (making a disease something personal, equal to a name, a character trait or a shape of one’s nose). Like on the visualization I was filming. ↩