Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 31 nr. 1, pp. 6-11

The following contribution is a written account of Jaana Erkkila-Hill’s keynote lecture at the FORUM+ symposium The art school as an ecosystem: Future perspectives on higher arts education, co-organised with ARIA during the research festival ARTICULATE on 20 October 2023. The event also marked the launch of the FORUM+ October 2023 issue and new dossier “The art school as an ecosystem”.

De volgende bijdrage is een schriftelijke weergave van de keynote door Jaana Erkkilä-Hill op het FORUM+ symposium The art school as an ecosystem: Future perspectives on higher arts education, dat FORUM+ op 20 oktober 2023 organiseerde met ARIA tijdens het ARTICULATE onderzoeksfestival. Het evenement vierde ook de lancering van het nieuwe nummer (oktober 2023) en dossier “De kunstschool als ecosysteem”.

Just as art lives outside the rules and predetermined boundaries, teaching art should also be free and based on artistic thinking, which is always born anew on a case-by-case basis. Artistic thinking is the cornerstone of the artist-researcher’s activities when considering pedagogical issues. Thinking takes place through artistic activity, in the form of paths that go in different directions. They criss-cross, alternate, and occasionally form a meeting point for an insight, a point from which a thought breaks out into something new. There is no use in teaching art from theories that are not based on experiential knowledge, the artist’s ability to think visibly and invisibly. It’s easier to describe the artistic thinking process as pieces whirling about in a three-dimensional space, which may sometimes form tendrils, chains, accumulations, which suddenly break out and start flying in different directions, no matter where to.

Jaana Erkkilä-Hill, Falling, letting go, linocut.

Juha Varto, Finnish scholar, philosopher, and professor in art education defines artistic thinking as using one’s own skill, evaluating it, positioning it, and developing it conceptually. The theory of artist pedagogy consists of practices, artists’ efforts to tell new generations that such a life is possible: the pursuit of the immaterial through matter, sound, bodily experiences, the sensual. All this is only possible in a free dialogue, where numbers and points are just distant noise, and everything important happens within the scope of artistic thinking; as a joint work between teacher and student, which can be part of the journey in growing up as an artist.

Artist-led pedagogy – The Nordic Art School

I am trying to share the development of my pedagogical vision, which has gone hand in hand with my growing up as an artist. The idea of artist pedagogy has been formed almost unnoticed over the years after working as a teacher at an art school for children and young people and later as principal at the Nordic Art School in Kokkola. There, the school’s founder Tage Martin Hörling (1949-2009) created a model of using visiting artists as teachers, whose merits were considered from the framework of artistic activity; no one asked about formal pedagogical qualifications.

Hörling was a Swedish artist who was trained at the Slade School of Arts in London. He founded the Nordic Art School in Kokkola in 1984. The mission of the school was to be outside of degree-orientated education, and at the same time to prepare students for applying to Nordic Art Universities if they wished to. The central teaching philosophy of the school was the idea of active artists manifesting different concepts of art in their own works and acting as teachers for intensive, mostly two-week periods. Students were exposed to different concepts of art, different teaching methods, and personalities, and thus they were also required to constantly self-reflect and think critically. If you did not get on with a teacher, you could always comfort yourself that they were gone after two weeks.

Outi Heiskanen and Jaana Erkkilä (Outi’s former student) teaching together in the Nordic Art School. Photo: Garry Jacobson. The Nordic Art School Archive.

Safer place in the arts? Photo: Michael Källström.

The idea of a safe space was far from the everyday life of the Nordic Art School, like in all art academies of the time. The actions of all the teachers who visited the art school would not stand up to ethical scrutiny according to current perceptions. The feedback given to the students could be cruel and belittling. Some were lifted and others were trampled, which was very common in the 1980s and 1990s, also in the art universities. Some kind of unspoken principle has been that if you can get through art education mostly with your wits about you, you are presumably good and strong enough to be an artist. I don’t defend that kind of pedagogy, but on the other hand, art is never a safe space, and an art student cannot be spared from a deep personal crisis regarding their own artistry. Admitting your own incompetence hurts.

I still strongly defend pedagogy based on artists’ authorship. Juha Varto writes about author knowledge and how important it is for authors/makers to write about their own field. Varto considers that the artist’s reflection can be considered a theory, if theory is thought of in the sense of the Greek language “to look further”. I think that Tage Martin Hörling created his own theory of art pedagogy, which he implemented in the teaching practices of the Nordic Art School, although he never wrote a book about teaching art, and he is not known as the creator of a pedagogical theory. Hörling is known as an artist, and it was his personal experience as an artist that made it possible to create a new kind of pedagogical model.

Hörling knew from experience how boring and all-consuming continuous teaching at the same organization year after year can be for an artist. The artist can give full-fledged student-focused teaching in short periods, when they know that they can return to their own studio to work on their own projects. This is also in the student’s interest; to get the teacher’s full attention and presence in the learning situation.

My own teaching has always been based on my own artistic activities, the innate understanding of artistic processes and the derived goal of piloting students to find their own artistic thinking, their own path as an artist and as a person. I keep asking myself if art teaching and art education have anything to do with each other.

Can teaching art be studied in any other way than through artistic activity? Why does the speech of educationalists in the context of teaching art feel so foreign? Why is it important to hear artists’ voices when it comes to teaching art? The research journey brings up more and more new questions, which is typical of artistic research: sometimes the result of the research is a new question that could not have been guessed at the beginning of the research.

Listening to the voice of an artist

Varto emphasizes the importance of the artist’s voice because the author writes, defines, sets boundaries of their own field at first hand, relying on experiential knowledge. According to him, most of these artists’ texts can be called “theoretical”, because the artists have stopped in the middle of their artistic activity to collect their thoughts, which artistic activity generates all the time. He writes about poets who have written more about artistic thinking than they have written poems. These ideas may well answer the questions of other art fields as well. Varto continues that this kind of cross-fertilization of art might be more successful than searching for wisdom in philosophy or economics, sociology or cognitive science.1

Along this path, I too have searched for answers in literature and music, when my questions have arisen from the field of visual arts. I have thought about the processes of making art, when the goal has been to understand teaching art, what it really means. When I teach, I think about how I think through making art, and I try to guide the student through their own process to the sources of their own thinking.

I have been trained as a visual artist and I see myself as a teaching artist, not so much an art teacher. I consider that I have the right to speak with the author’s voice in the areas of making art as well as teaching and researching it.

Collaboration as pedagogy. Creating an installation together with Alexander Granqvist. Photo: Jaana Erkkilä-Hill.

For years, I have strived to work dialogically with my students and thought that I would encounter a foreign culture in them, the individuals, which I approach with curiosity. The polyphonic structure of the images is based on the idea of the dialogic nature of human thinking which Bakhtin2 describes as the opposite of unanimity that seeks the truth. Bakhtin refers to the Socratic notion of the co-creation of truth between truth-seeking people in their dialogic interactions. When this kind of dialogic way of working is used in connection with art education, I have found that the less I try to influence my students and the more I let them influence me, the more interesting the teaching work and its research develop.

The focus shifts from teaching the student to the teacher’s learning and the realization of the artist’s work in the teaching process. Such an approach is only possible when both the teacher and the student are involved in artistic creation, in a free dialogue. Art is born not only from lived life and its observation, but also to the greatest extent, from art, from the texts of others, in whatever form they are read, as images, movement, soundscapes, one another as interconnected words.

Attentive understanding

Mihail Bakhtin’s3 interpretation of Dostoyevsky’s polyphonic novels, in which different narrators’ voices are mixed and where there is not one all-knowing narrator, but each one has their own autonomy and fullness, point my way as an experiencer of art, author, researcher and teacher. I am fascinated by works in which the voices of several authors are mixed, art forms intertwine and the works talk to each other, losing their interest in the named authors. The author can be another, unknown, which is created when the teacher’s and student’s works change from being an object into a subject.4

I experience art as a holistic sensation where it is impossible to separate content from form. Sometimes the rhythm of the language is more meaningful to me than the subject matter, what the language says with the words. You know the reality revealed by art for sure, even if you can’t argue with words. I considered Heidegger’s idea of attentive understanding.5 This soot can never cover up and be untrue. Through sensory perceptions, i.e. understanding art, one can move towards a pure attentive understanding. Perceiving through the senses is an active event that can include not only active receiving but also active doing. It is an event that may lead to the creation of a work or give an answer to the questions posed. It can also give an answer to something you didn’t even understand to ask.

As an artist, I live in a non-linear time, I travel through years and decades, always returning to themes that I already thought had sunk into oblivion. I am a visual artist, but when I want to understand as a researcher how I build the world, how the landscapes of my memory and memories are formed, which would be important when we talk about teaching art, I turn to literature and feel how reading affects my visual thinking. Marcel Proust ponders the importance of sensory experiences for our memories and the possibility given by those experiences to move between different times, to live simultaneously in the past and the present. Proust writes about intrusion of the past into the present and how he no longer knew which time he lived in.6

Artistic thinking is the cornerstone of the artist-researcher’s activities when considering pedagogical issues.

For me, images are born from literature, from the worlds of words with borrowed concepts and figures of speech. I linger on the words, even if my thoughts are slowly forming into images, visible and understandable with eyes. In recent years, several books and studies have been published that deal with understanding the world and life through the reception of visual arts7 and different areas of art as some kind of tools for sense making.8 These texts are referred to and talked about as new ideas in art education and art research. In a way, Marcel Proust wrote about the same thing in his search for the lost time. However, Proust turns his gaze to the reader, the experiencer themselves, instead of the external world: “In reality, every reader is a reader of himself.”9 The act of entering into dialogue with other ideas can be looked at in many ways.

Personally, I find myself getting upset when a researcher approaches the process related to art making or visual perception and explains how the image is created, what the viewer experiences and how the art affects. An educationalist tells how art should be taught and what theory is involved in learning, just as if an artist practising their profession could be forgotten and ignored as some insignificant and silent statistic on the stage of art education. Those who have either stopped their own artistic activity or have never practised it speak loudest about the radical change in art education in the future compared to the past. A shared meal or conversation does not become art just because someone defines it as such.

In the case of socially engaged art, it is equally important to ask whether we are dealing with high-quality art or whether it is simply a social activity that has nothing to do with art in itself. What are the artistic goals of the event or act? If the goals are purely social or connected with societal impact without artistic quality we should not talk about art but something else that has an independent value in society.

How to become No-one?

The American artist Agnes Martin has said that she did not even try to do her own artistic work during the times when she was teaching.10 According to Martin, both painting and teaching are jobs that require so much concentration that they cannot be done side by side. Many artists feel that way, but you can also experience teaching as a part of your own artistic working process, and I am not talking about participatory art in the form that it has been presented in connection with various community projects. Just as there is always a reason to ask what art is, it is good for those working in art education to ask time and time again what it means to teach art.

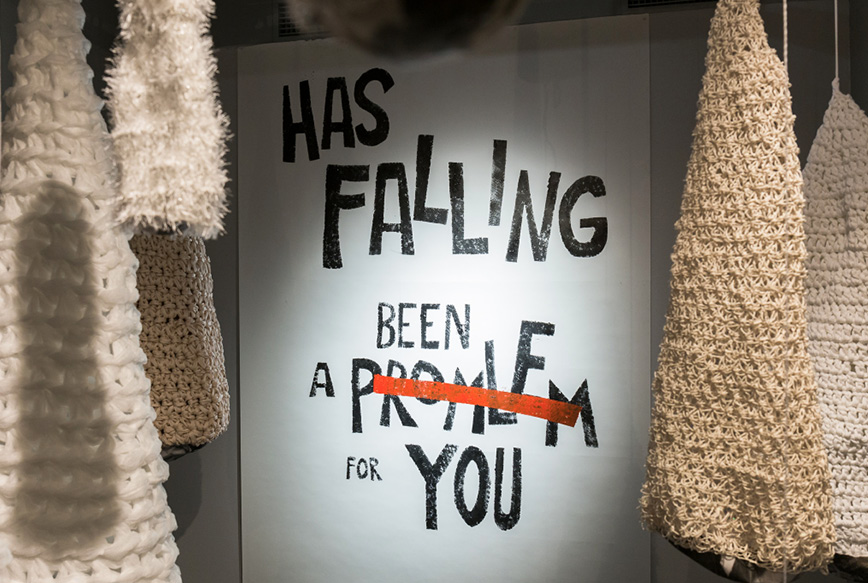

"Has falling been a promlem for you?" Detail of an installation by Jaana Erkkilä-Hill, Eija Timonen, and Heidi Pietarinen.

In connection with making art, we talk about skill. Hegel simply writes that the artist needs skill in order to master external matter and not to be hindered by its resistance.11 There are many kinds of skills, and technical, hand-related skills are not the most important in teaching art, but you cannot do much without them either. The most important thing is the skill of triggering out of non-existence something not yet revealed, waiting to be perceived by the senses. Humility, the understanding of the impossibility of perfection, is closely related to skill. Martin writes about discipline, continuing work without resistance or without preconceived notions. According to her, discipline is to continue to work even when hope and desires have been left behind. To proceed without self-speculation, to act impersonally, is self-discipline. Martin claims that not thinking, not planning, not calculating is self-discipline. Martin talks about giving up on yourself and wanting something.12 Maurice Blanchot says that a writer becomes a writer when they stop saying “I”. According to Blanchot, when writing, one becomes an echo of something that cannot stop speaking. When writing is a surrender to the power of the Infinit, the writer who agrees to support its essence can no longer say “I”. In this situation the writer speaks of the fact that in one way or another, he has ceased to be himself, and he is no longer anyone.13

In a world where everyone should become Someone, it is difficult to learn and teach becoming No-one, even if it is the only path to liberated expression. Surrendering to an unpredictable dialogue, agreeing to let go of the idea that the destination is known and attainable, requires discipline. Education is often associated with the idea of climbing the ladder of knowledge, rising higher and higher. One of the most important skills in growing up as an artist is the art of falling. You have to dare to do what you don’t know how to do, to go where no paved road goes. Letting go of the personal requires skill.

The skill is giving up on yourself, the headstrong courage to jump even when you are not sure if the wings will carry you. How can such skills be taught in a world where education is expected to lead to success in both economic and social prestige. Do you dare to jump, to fall? How do you learn to fall?

+++

Jaana Erkkilä-Hill

is the Vice Rector for Research at the University of the Arts Helsinki and holds a Professorship in Fine Art at the University of Lapland. She graduated with a Master of Fine Arts from the Academy of Fine Arts Helsinki and a PhD in the Arts from Aalto University. Her research interests lie in the field of artistic thinking and artist pedagogy. She is currently a member of the FORUM+ advisory board. In addition to her academic career she is active as an artist. Her work is held in several public and private collections.

Noten

- Varto, Juha. Taiteellinen tutkimus. Mitä se on? Kuka sitä tekee? Miksi? Helsinki, Aalto-yliopiston julkaisusarja. Taide+Muotoilu+Arkkitehtuuri, January 2017, pp. 58-59. ↩

- Bahtin, Mihail. Dostojevskin poetiikan ongelmia. Helsinki, Kustannus Oy Orient Express, 1991, p. 162. ↩

- Bahtin, pp. 36-37, pp. 52-57. ↩

- Erkkila, Jaana. Tekijä on toinen – kuinka kuvallinen dialogi syntyy. October 2012. Aalto-yliopiston julkaisusarja, PhD dissertation. ↩

- Heidegger, Martin. Taideteoksen alkuperä. 1935. Kustannusosakeyhtio Taide, 1998, p. 57. ↩

- Proust, Marcel. Kadonnutta aikaa etsimässä. Jälleenlöydetty aika. Keuruu, Otava, 2007, pp. 218-19. ↩

- Armstrong, John, and Alain de Botton. Art as Therapy. Phaidon Press Limited, 2016. ↩

- Noe, Alva. Strange Tools, Art and Human Nature. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015. ↩

- Proust, p. 267. ↩

- Martin, Agnes. Hiljaisuus taloni lattialla/The Silence on the floor of my house. Vapaa Taidekoulu, 1990, p. 97. ↩

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. Taiteenfilosofia, johdanto estetiikan luentoihin. 1842. Gaudeamus, 2013, p. 77. ↩

- Martin, p. 15. ↩

- Blanchot, Maurice. The Space of Literature. 1955. University of Nebraska Press, 2003, pp. 23-25. ↩