Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 32 nr. 1, pp. 22-31

Meerdere wezens die één worden. Koorden en akkoorden die grenzen vervagen

Eliana Sánchez-Aldana, Isabela Ortiz Jaramillo, Laura Díaz-Dangond, María Alejandra Cubillos Garay

This is a fictional story that questions the traditional interweaving of technoscience. It goes through the fibres to un-weave or un-make the essentialist borders created between humans and machines. We use weaving as a thread that helps us to rethink the distance between the three components of HCI: humans, computers, and interaction. We tell the story of weavers, looms, and threads assembling as an accord that is not an interaction but an intra-action. The text itself shapes the argument and introduces the reader to the creature.

Dit is een fictief verhaal dat de traditionele verwevenheid van technowetenschap in twijfel trekt. Het gaat door de vezels heen om de essentialistische grenzen tussen mens en machine te ontweven of te ontwarren. We gebruiken het weven als een rode draad die ons helpt om de afstand tussen de drie componenten van HCI te heroverwegen: mensen, computers en interactie. We vertellen het verhaal van wevers, weefgetouwen en draden die samenkomen als een akkoord dat geen interactie, maar een intra-actie is. De tekst zelf geeft vorm aan het argument en laat de lezer kennismaken met 'het wezen'.

Introduction: On how to read this text/textile/code (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Black and white grid to explain the plain weave.

This chapter explores the tensions that arise at the intersection of human and non-human, analogue and digital, theory and practice. Through weaving – a practice that combines body, machine, and material – we examine how these tensions can be reconfigured to generate new ways of thinking and creating.

We begin, as we once began weaving, with a simple set of black and white squares. This elementary pattern taught us by Maarit Salolainen, a Finnish weaving professor, represents more than a starting point. It illustrates the foundational principle of weaving: the interplay of contrasts, like warp and weft, fullness and void, or ones and zeros in a digital processor. These contrasts, far from being opposites, are interdependent. Their tension produces something entirely new – a fabric, a system, or a story.

We weave as both a method and a metaphor to question established binaries, such as those just mentioned. Drawing from our experiences as four women and textile makers, we reflect on our material engagement with the loom – a machine that transforms threads into textiles and mediates the relationship between body and material. A multiple that acts as one. From the heart of weaving, an intersection of yarns and bodies that become one.1

This is not merely a theoretical exploration. It is a written experiment that combines theoretical and empirical approaches. When thinking and talking about the interaction with our looms, the threads, and the needles, we draw on theories, concepts, and written knowledge about it. By weaving together our embodied experiences and critical reflections, we attempt to un/make and reweave the very fibres of technoscience.2 The text itself mirrors this process: it is at once a textile, a text, and a code. Its structure oscillates between binaries traditionally considered opposites. But they are two ends of the same thread that produce a tension.3 Together, the binaries co-exist as a whole piece. They need each other just as the weft needs the warp to weave the fabric together or as we weavers need the loom to weave. So it is, our text is woven in white and black types. And to guide you, the reader, through this woven narrative, we have divided the chapter into sections that reflect its dual nature. The theoretical aspects are presented on white backgrounds, while the empirical insights – rooted in the embodied experience of weaving – are found on black backgrounds. These sections invite you to explore the interplay of theory and materiality as we narrate how our bodies and our looms work together to create something beyond either of them.

Our story is tangled at times. It attempts to navigate the tension between fact and fiction, between the real and the imagined. Drawing on Donna Haraway’s “Speculative Fabulation,”4 we construct a narrative that blurs the boundaries between human and machine, analogue and digital.

Our story consists of four tensions: The first tension explores the historical distance created between analogue making and digital thinking, questioning whose bodies and stories have been excluded in the history of computing. The second tension examines the relationship between human and more-than-human bodies, highlighting the choreography that emerges in their interaction. The third tension dissolves hierarchies, creating a new character that exists only through the act of making. Finally, the fourth tension blurs fact and fiction, inviting you, dear reader, to join us in this playful unravelling of what we know and what we imagine, and to meet the creature.

Tension 1: Why we? Why looms as machines? Why weaving as coding?

Why do we dare to talk about the borders between humans and computers? Three of us are designers. One of us is an artist and a litterateur. One of us is also an engineer. The four of us are embroiderers. Two of us can code looms because we are weavers. And one of us can code software because she is a coder. We, four women, four Colombians, four textile makers. We want to say something about the boundaries shared, and the tensions created by the two components of a binary. We come to talk about the boundaries created between binary worlds, human bodies and machine bodies, theory and experience, facts and fiction. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2: Four women: Weavers, embroiderers, writers, and programmers.

We doubted before we started. We doubted we had something to say because we felt we were outsiders in this land. Women’s contributions to computers and the programming world have often been overlooked as if they never existed. As was the work of Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, better known as Ada Lovelace, who created the first algorithm to be executed by a computer.5 Or the work of Dorothy Vaughan, a mathematician and expert programmer with a key role in mastering early programming languages. Above all, we come to a world we women once inhabited, but from which we were later expelled, with our voices erased from the books. We come to talk about our interaction with computers.

Technological developments are correlated to men’s domains, which produces differentiated access to knowledge. As Tabet puts it, “keeping us women away from knowledge [erasing our hands from its production] is one of the primary forms of oppression as it has been the distinction between knowing and making”6 – mind and body, theoretical and empirical, power relationships that produce the subaltern. Women’s work is responsible for looking after the body so that men can be free to think and make science and technology.7

The voices of we makers, women, and mestizas from the global south have been ignored for a long time. We consider our subalternised location not as a statistical concept but as a revolutionary, critical index.8 We are here to oppose the established orders, to un-make them using our textile logic. We take Spivak’s question: “can the subaltern speak?”9 and we expand it. We ask if we can speak and, moreover, if our empirical voice will be heard.

We dance with the machine to make a textile.

We also want to hear the voice, see the role and agency of more-than-human participants, who have also been made invisible, and try to listen to what they say. An embodied approach acknowledges that theory production starts with practice,10 with empirical experiences situated in human materialities and more-than-human bodies.11 We want to offer new perspectives on reality: reimagining technoscience and fiction seeks to incorporate an embodied epistemology and narratives, highlighting the evolving interplay between knowledge and reality. The knowledge that resides in our body, in the traces of our fingertips, in our eyes, or in our legs, is what gives us the capability to speak about our relationship with machines. Our situated knowledge is our closeness to the looms, threads, drawings, movement and machines – or computers. We have our own experiences, our human materiality meeting more-than-human bodies.

Calling attention to the participants’ bodies in the weaving scene helps us remember the need to erase the passage of the textile maker’s hand, the female hand. Throughout history, what has been considered a ‘perfectly’ woven, embroidered or sewn piece, is a piece where the hand that made it, most likely a female hand, remains invisible. The female hand that never leaves a trace is considered a hand that is doing a good job.12 Our work as textile makers is appreciated as long as it is perfect, without mistakes and amendments. We have been asked to make our presence disappear.

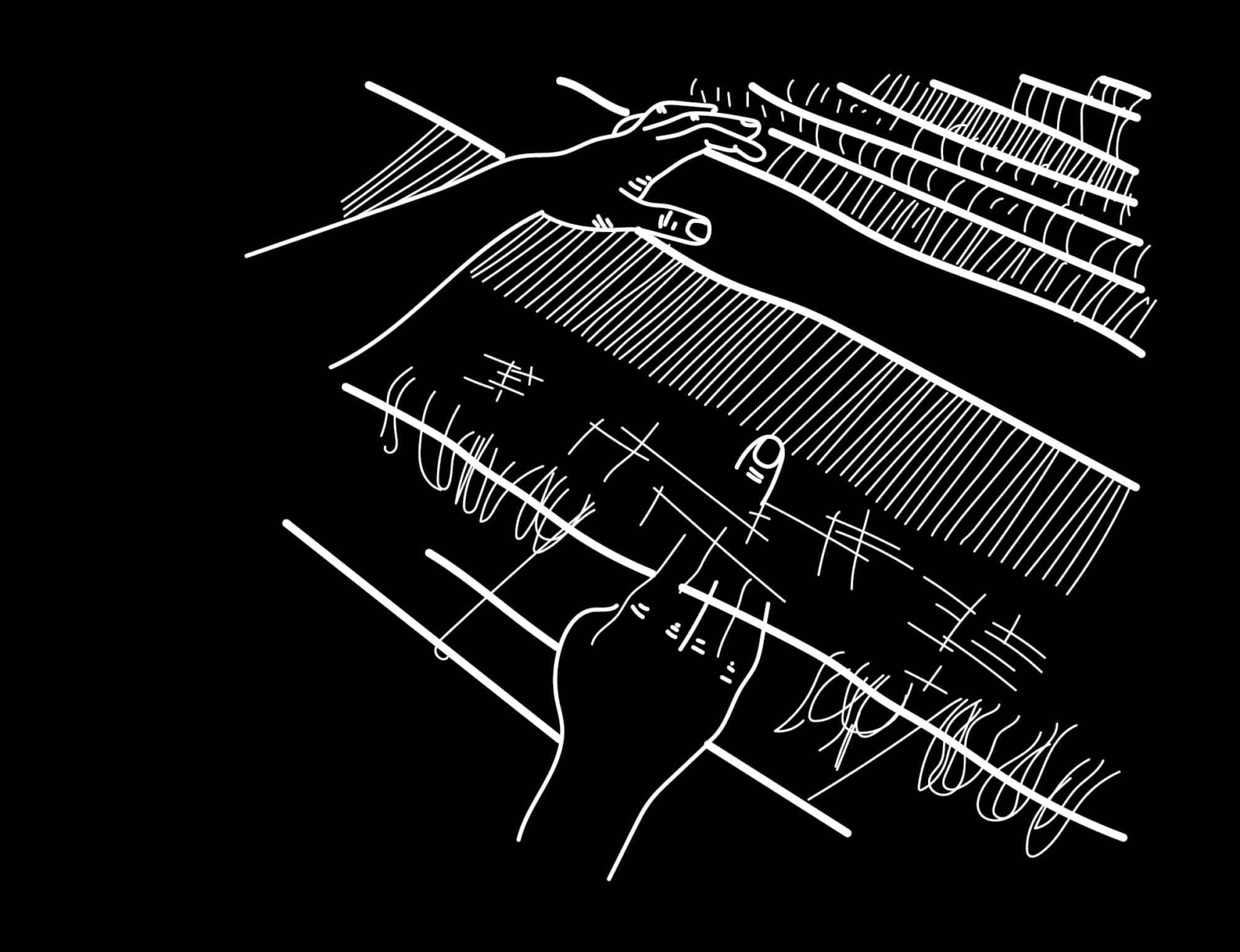

Not only is the female hand erased from the process of making and caring; so are the machines that make. The hand of the woman who wove remains just as invisible as the loom that held the threads. It would be unthinkable – if even possible – to know how many needles, threads, or hands took the time to care about weaving a certain fabric. Moreover, that is the point of a good loom and a good hand; that careful work is meant to disappear, and with it, the material knowledge that was built among the hands, the threads and the many hours that went into making them.13 (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: The Fabric

Figure 4: The Machine

Figure 5: The Weaver

We just get to see the interface that is produced by the human and the machine: the textile. However, as weavers, our bodies are aware that much more is produced beyond the fabric. As the warp is being interlaced with the weft, and with the same rhythm the fabric is being produced, there is an ongoing knowledge production as we “think through making”14 and the knowledge begins to inhabit the human body and the more-than-human bodies.

Weaving is a technique to make textiles by interlacing two groups of perpendicular materials. Woven textiles are made of a first set of threads (the warp), which gives the structure and dresses the loom. And a second set, which is interlaced, woven, and perpendicular to the warp (the weft). We will focus on floor-mounted handlooms since those are the ones we weave with. The heddles hold the warp’s threads in the shafts of a floor loom. And the shafts are in charge of remembering the threading – we could say that this is the code that runs on the handloom. It gives commands to the warp’s threads to go up or stay down to allow the weft to pass. We code a loom manually. The shafts are connected to the treadles, and we, the weavers, activate the shafts by stepping on the treadles with our feet. We dance with the machine to make a textile. We will not go further. It is a complex process. But these parts are essential to explain our plot. This is a ‘basic’ floor loom, the key species of this text. (Fig. 4)

(Fig. 5) The machine has served as an extension of the human body, as Zafra says, to expand its capacities.15 Throughout history, we have looked for different extensions that lengthen us, more than life, to reach the capabilities we want to achieve. We look for ways to extend our limbs to supply our needs. As humans, we have needed to create ways to expand our bodies’ capabilities in space because we constantly seem to require more space, to claim more space. We expand our borders.

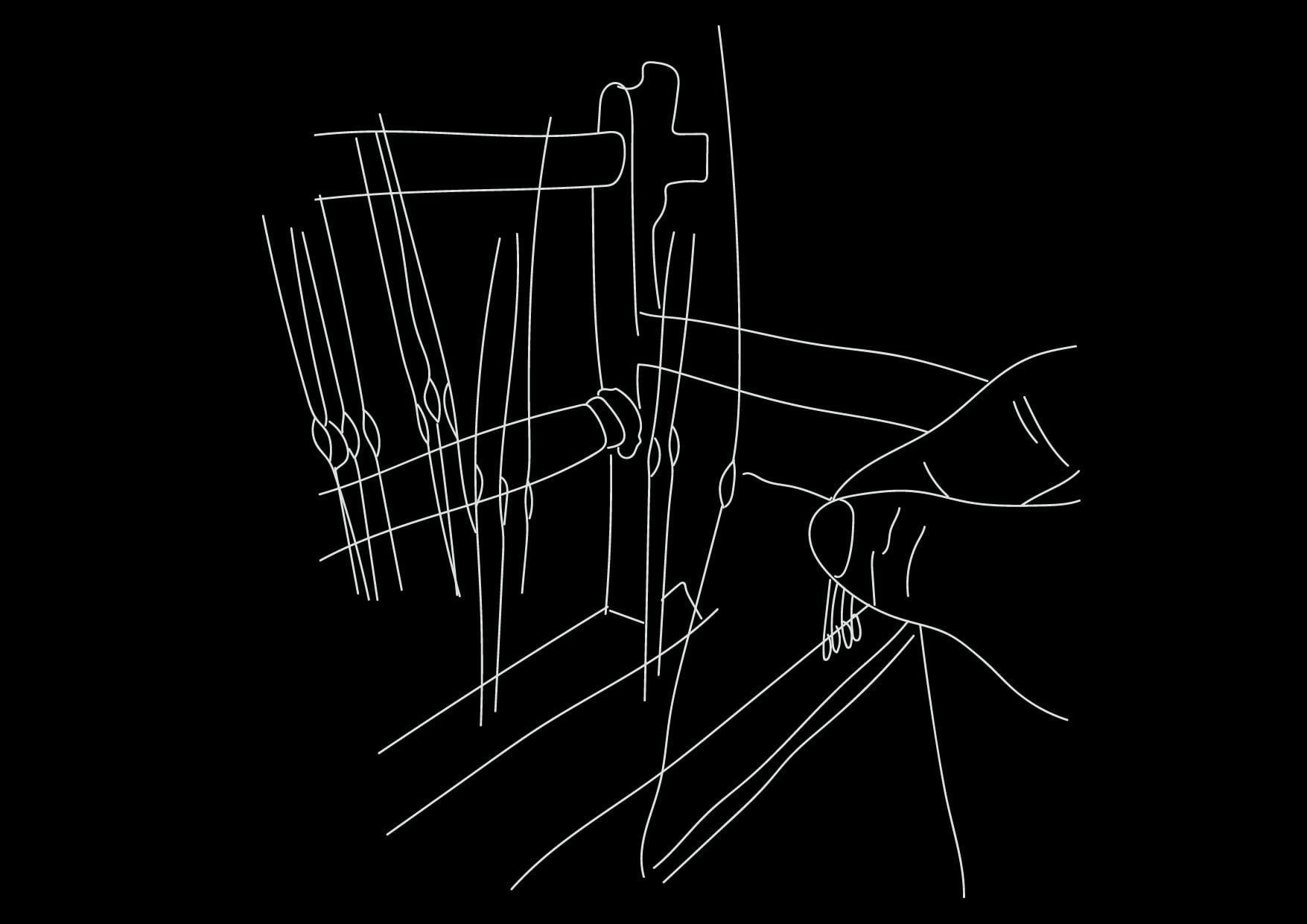

Figure 6: Threading the Heddles

And so, the machines become our prostheses to reach all that our body cannot, as the needles in the shafts do. They are more thorough than our fingers when it comes to calling to action individual threads. So we agree to assemble with them, to expand our skills and to maximize our energy. Hence, prostheses help us expand our capabilities and create worlds – sometimes textile worlds – that our bodies alone cannot build. (Fig. 6)

In 1801 Joseph Marie Jacquard built a machine to add to a floor loom. It helped to speed up the weaving process in horizontal looms with a new system of punched cards. The cards were placed in a machine directly above the loom, and each card decided which threads moved up and which stayed still. Where there are holes punched in the card, the threads go up. And where there are no holes, the thread of the warp stays in place. The punch cards are the code for the print in the weaving. Similar cards were later translated and used in early computers to store data and instructions. Where there are holes in the card, there is a one (1), and where there are no holes, there is a zero (0). The punch cards used in a Jacquard loom had the same logic as the computers, like two ends of the same thread. What Ada Lovelace first called the “thinking machine” does not begin with writing; it is directly related to the weaving of “elaborate figured skills”.16 Jacquard looms and computers are both machines with a common ancestor: the floor loom. In her 1843 notes on Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, Ada linked the loom and the computer: “we may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.”17 Both machines work with binary logic – ones and zeros, positive and negative, thread and no thread. Loom and computer. Both machines, or should we say from now on, THE machine.

Intra-actions between weaver, loom, and thread blur the lines between human and machine.

Algorithms are the base of computer programs. They are the set of instructions we give a computer to accomplish a particular task, just as we code the loom by deciding in which order the heddles go up or stay still. But the word “algorithm” existed before computers. The term algorism comes from a number system, “a set of rules or a step-by-step procedure for solving a problem or accomplishing a task in a finite number of steps.”18 And it was associated with a skill related to the crafts of writing, drawing, and needlework referenced on the tombstone of Elizabeth Lucar, an English calligrapher who was also a seamstress and an early adopter of algorithmic calculations. The tombstone, providing insight on the intellectual achievements of this Renaissance woman, implies that algorithms were – and are – part of feminized spaces as textiles are. Before the computers, they were women’s algorithms.

This is how the first two characters of this story begin to come in contact: the weaver uses algorithms to start the conversation with the machine. With a binary language of ones and zeros, a full and a void, a thread that goes up and down.

Tension 2: The accord

So far, we have addressed and presented two of the three characters of our story: the weaver and the machine. Now, we will talk about the third component: the action, as the medium that unmakes the borders amidst the components, the human-weaver and the loom-machine.

To question the idea of interaction, we refer to Karen Barad and her concept of intra-action.19 She considers it as the mutual construction between two or more subjects or participants. The “inter” in interaction means “in-between.” It refers to what happens between the weaver and THE machine when they both exist in the same place, facing each other and performing individually but with one another, as when the coder presses the keys of her computer. It preserves the unicity of two separate subjects that already exist. Meanwhile the “intra” in intra-action means “from the inside” – when the weaver and THE machine perform together, they need each other. So, the weaver cannot weave alone, she needs THE machine, and THE machine needs the weaver in return. The loom cannot weave alone, nor can we, nor the threads.20 With an intra-action, something different is produced, and it only appears when they perform together. Not before, not after. At the very moment, they gather.

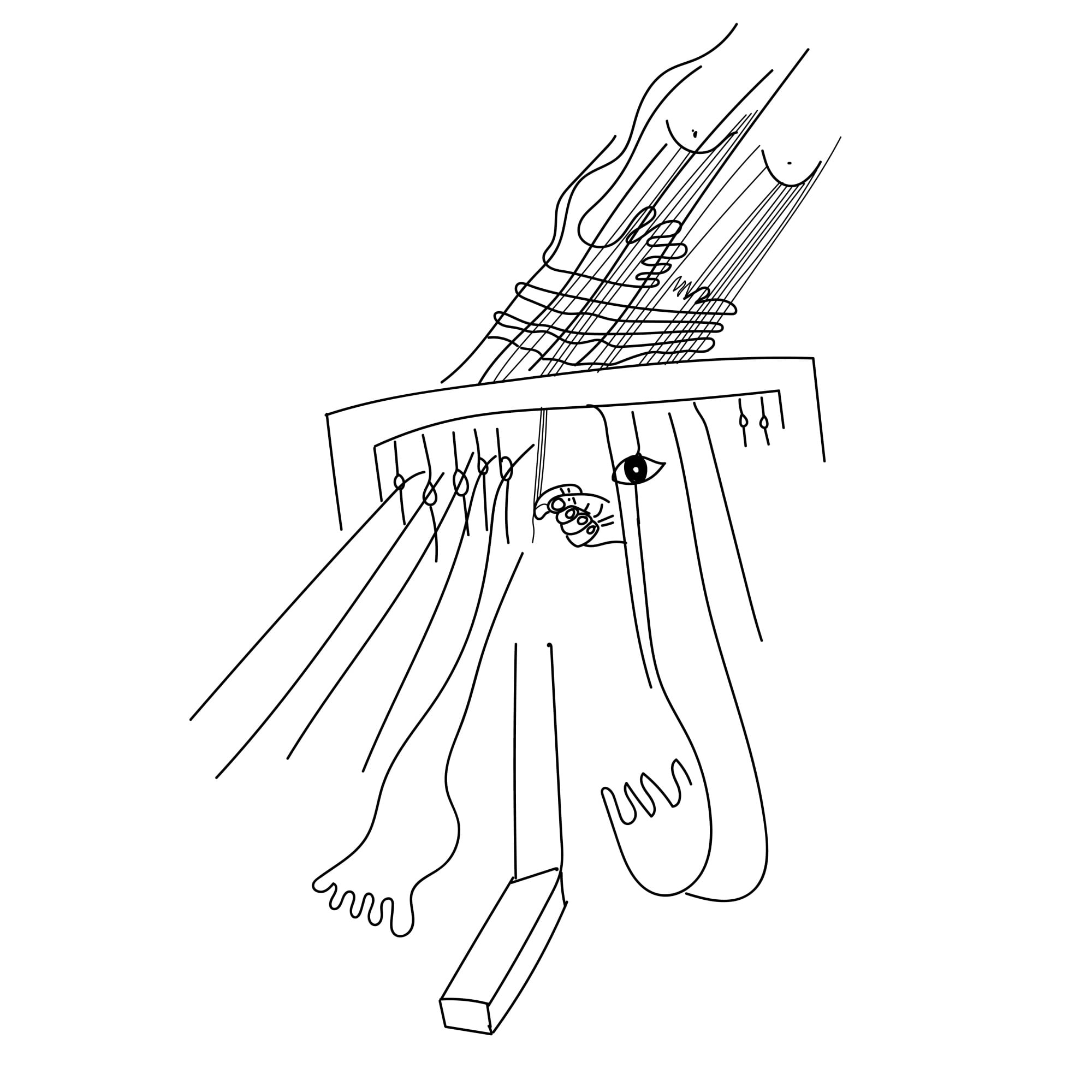

We could see our two characters as two separate components. However, we think, and we have experienced, that what happens between weavers and machines is not an interaction but rather an intra-action. And as we unmake stitches and loops, we wonder if we can unmake the borders between them, between the binary, and remake them as a different creation that is born when the ‘weaver-machine-intra-action’ takes place. The concept of intra-action helps us explain what we feel in our bodies together with our looms, threads, and movement when weaving. We feel our bodies expand and trespass the boundaries between human and machine, making us part of a synchrony, a chord, an accord, a single entity that acts as one, as a single creature. (Fig. 7)

Figure 7: Accord between body and machine

Figure 8: Hybrid Algorithm

(Fig. 8) Is this the base of algorithms? A full and a void. Could be called a chord.

The chords of the loom begin to be established when a warp begins to be assembled, when the sound of the tensed threads is understood, the sound of the pedals that go up and down, the shuttle that passes from one side to the other creating a weft.21 Both weaver and machine must agree to understand the same language to come to an accord. The chords of the loom consist of full and empty, up and down, ones and zeros that encode a code, a code that is possible thanks to accords.

Figure 9: Hands and Threads speaking the same language

(Fig. 9) New dynamics begin to open up, because by extending ourselves next to the machine we stop being only human, our body creates necessary dysmorphia and precise adaptations to fit with the machine, to reach an accord. Programming implies an accord between the person and the machine. We stop being human and machine; the differences that make the borders start to be challenged. Who is the object and who is the subject? Programming involves a language that enables communication between humans and machines, extending our capabilities beyond physical and mental limitations. It represents a way to bridge the gap between our body’s restrictions and the possibilities of our imagination. By creating technological extensions, we can transcend the barriers of our physical form, even as we continue to imagine ways to overcome these limitations.22

To start weaving is not a quick process. We have an idea of what we want, it takes shape in our mind, but even when it is intangible it is a matter of matter, we think in material shape. We negotiate with the material characteristics of the threads and the loom. The width of the loom, the colours, the texture of the threads, the number of heddles. We agree to work with its characteristics and it agrees to work with ours. We create the algorithm.

Figure 10: Intra-Action

(Fig. 10) So, we set the threading. We sit in front of (we would say, almost inside) the loom and, thread by thread, we dress the loom. At the very moment when we are dressing the loom, we make our bodies available for the loom, and the loom makes itself available to us. We cannot do or think about anything else; we are part of nothing else. It’s just the machine and the body. The human arm must pass through the front part of the loom, then through the heddles, to finally grab the thread that we must conduct all the way back to us in the front of the loom. This is the precise moment of intra-action.

This is a perfect choreography in which we must sing a song to keep the rhythm going: 1 black 2 white, 1 black 2 white. We repeat it until the end of the threads, following the algorithm. Once we, both the loom and the weaver, are ready, we can start to weave. We dance the coded song. We play it synchronically with our movements, the threadless and the threads. We never feel like we are weaving alone. We feel the tension if something happens with the threads or the loom. We move as one. We co-reason.

Figure 11: Being one with the loom

(Fig. 11) So, we communicate and accord how the woven fabric looks. The shuttle takes the bobbin that holds the weft thread and joins the dance, sliding through the warp from side to side, of the multiple as one. (We are a multiple that acts as one.) We all know that if something is not going the way it should, it is when something has broken the accord. We, the human component, hear when one of the treadles gets stuck and, for some reason, can’t raise the threads. We can also see – or even feel – when even just a single thread from the warp breaks, and we must stop the rhythm and knot the parts back together. But we also know when we are following the algorithm. The sounds, as voices, the rhythm (or ‘rithm’) as a conversation show us that it is going as it tells us to move.

It is an accord that is formed by a chord from which we have to keep a record of every time the process starts again. As Alexo Grijelmo says, to record shows us a contortion of the concept of recall that takes on a reflexive value (the action that is reflected towards oneself)23 because what we remember is what our heart keeps and makes it beat, and it sends us to memory. We record the processes, the techniques and the forms because they make our heartbeat; because they are connected to our body, it goes beyond a craft. It is a making that resonates in the body, leaves a trace in the touch, the making with the machine does matter and it impacts our lives, it deforms us. The machine is not at the service of the human, they are together in a single team.

Tension 3: The Creature

The creature can only take place when the weaver and THE machine accord to work together. When both human and loom are willing to engage in the act of weaving, of working together for a mutual goal. Revisiting Haraway’s Speculative Fabulation, we understand that the creature is born as a merge from both weaver and machine, and not as a domination of one over the other.24

Barad’s intra-action helps us understand how one thing cannot work without the other – how the weaver cannot weave without the loom (as the coder cannot code without the computer), and how some threads of the warp are coded to come up and others have to stay down and hold the weft. And also, how the absence of a thread needs to exist for the whole to be seen. The machine and the weaver co-create. A weaver cannot define the algorithm without knowing how to weave, and the loom cannot weave something beyond its scope. They visualize together and define determined conditions together, and that is why the creature can create.

Because the human-subject needs the machine just as much as the machine-object needs the human, we realize there is no big difference between one and the other. We are both – the weaver and the loom, subject and object, who controls and who is controlled. Human agency and its ‘natural’ hierarchy are questioned, and we acknowledge a machine’s affectations on us.25 We add the loom’s agency, so the intra-action is not the addition of isolated units acting together but the amalgam of participants’ agencies acting as one. We become something different, not the same as another or each other. We become, with the loom and the threads, something different.

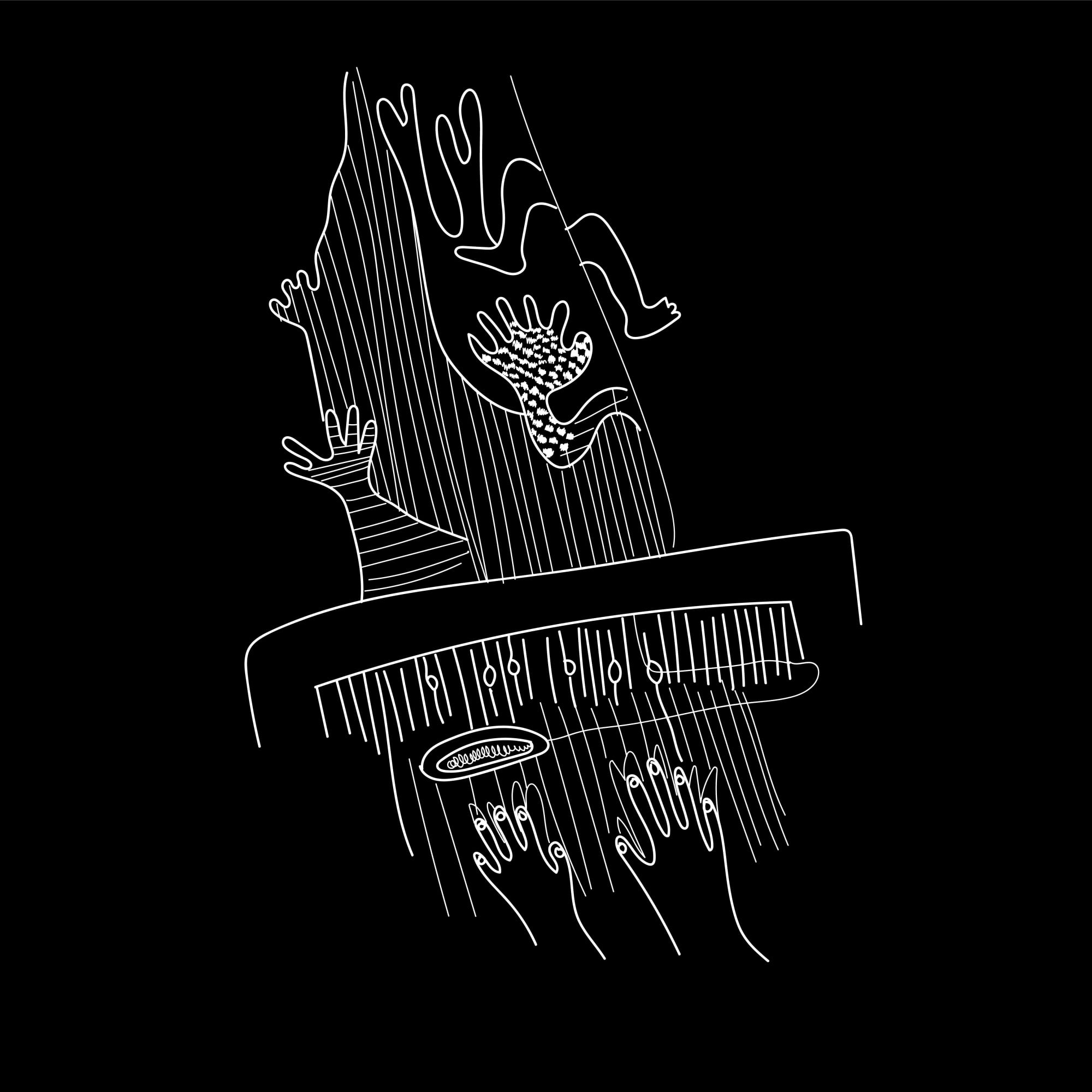

This is why, to reach these accords, we have to stop being only human, blur ourselves, give some responsibilities to other entities, to other parties, and accept turning into something that is not us nor the loom: a new creature. (Fig. 12)

Figure 12: A new creature

Our creature is inspired by the one made by parts of other bodies, assembled by Doctor Frankenstein and created by author Mary Godwin, known as Mary Shelley. These parts of other bodies that make up the creature are dead and ‘useless’; when they come together correctly life is given to this creature so that it can stand on its own. They expand and become something new together. We, our living and moving body with the loom in action, are the creature, a creature made of parts, some of which are alive and are used for other limited things and some of which are inert until that intra-action. We are no longer just human or just machines. Nor is the fabric that is being woven just a fabric. It is also part of the creature. It is becoming fabric at the same time we are becoming the creature. We are the product of what we make, and we are part of what we create. (Fig. 13)

Figure 13: Skin and fabric, part of the creature

Figure 14: Becoming the creature

(Fig. 14) Where we should direct our gaze, where this text and our making find meaning, even the making of many machines, is in the moment of action. Here, individuality dissolves, the new is discovered, the blend occurs.

The moment of action should be able to extend over time because it is when ideas take on meaning, when what is made gains substance, acquires a form, and one can achieve an improvement of technique. Action is the only way to make, to exert, to create, to make mistakes, to merge. Action demands complete bodies, entire minds. It makes us think; it becomes a repeated action, but it is never the same. Even with the same gesture, it improves, changes, modifies the method, and ruminates upon itself.

Maybe the creature is not a noun but a verb, as it only exists in action, in the intra-action of bodies. Together, they can create things, think, extend their limited capacities, and give life to something new – an idea that can be touched. It transcends the empty and simple category of an idea, becoming something tangible: be it good or bad, a ‘product’ of an action.

Products are already made, all designed, all invented. The key lies in how we have intervened in all those forms of action, how we have learned to act differently, to act with others. Inverting roles, body as machine, machine as body, facts as fiction, experience as facts – everything stirred and intertwined simultaneously.

Tension 4: Conclusion – invitation

Our experiment is a simple story, a fictional (?) story, that questions the borders that make us human or machine. It is a speculation to challenge dominant paradigms to rewrite history,26 to unmake borders between what the creator uses to create the creation: an interaction between participants. It is an encounter that respects the borders. We erase the borders between fact and fiction to inhabit a space where the tensions between the binary are visible. When weaving, the human weaver and computer machine become something else: a new creature. We assemble to make the textile, make ourselves, unmake our borders and act as an organism that only exists intra: from the inside.

The creature might be close to Haraway’s cyborg,27 both machine and organism, nature and culture all at once. In this encounter, parts can keep their individuality but act as one whole – a questioning of the essentialist ideas of the individual’s non-divisibility, of the individual’s unity. Participants divide, expand, change, mix, contaminate, become one. We wanted to give an illustrated and embodied example of what we feel Barad’s ideas on intra-action feel like.

It is an embodied story between looms and weavers and threads that can act separately to make one, and an invitation to imagine new ways of thinking about our relationship with more-than-human subjects.

This is a speculative fabrication designed to evoke tension in our relationship with machines and question what we have asserted as certain, as absolute truth. The creature is merely another fiction of how we feel when we inhabit the loom, when we make it on the loom. Frankenstein’s creature was also a fiction of humanity itself. Perhaps we find it easier to accept fiction as fiction, and it is precisely there that we can dissect all those components that make up what reality is, or at least what we have declared to be reality. Fiction allows us to give language to that which has yet to be named, to give meaning, a voice, and a space to that which exists only in the abstract and often in solitude. We have turned to fiction as a narrative and graphic strategy to show and share this experience and cast doubt and tension on the different relationships among ourselves and the machine itself.

Maybe everything we’ve previously stated with a black background is reality for us – it’s how we comprehend the world and experience it. Perhaps all the theory and history we narrated above with the white background, with technical forms, is fiction – a fiction we’ve chosen and embraced, but ultimately fiction. Who could genuinely know? We leave you with the doubt; perhaps as you read, you’ll discover which is which or choose which is ‘reality’ for you, if that truly matters. We embrace this series of dualities (all those mentioned above) as complementary parts, as elements that need to coexist, even exchanging roles, loosening and releasing while yielding and assuming.

+++

All illustrations in this article are part of the series Hybrid Algorithm (2023), created by María Alejandra Cubillos-Garay for “Multiples Becoming a Single Creature”.

+++

Eliana Sanchez-Aldana

is a designer, weaver, and practice-based researcher who works with and learns from textiles. She both creates and studies textiles, viewing them as ecologies with unique world-making practices that can shape design. She holds the position of Associate Professor in the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Universidad de los Andes, Colombia.

Isabela Ortiz Jaramillo

is a designer and computer systems engineer passionate about overcoming stereotypes associated with programming. She explores creative coding as an interdisciplinary medium, unlocking new possibilities in various fields. She is a Lecturer in the Faculty of Architecture and Design at Universidad de los Andes, where she teaches computational thinking and web design.

Laura Díaz-Dangond

is a designer. She explores textiles through various techniques, aiming to approach design by reflecting on the materiality of creative practices. Her interest lies in understanding the relationships and interactions between makers and materials within textile practices. Through this exploration, she has identified herself as an apprentice weaver.

María Alejandra Cubillos-Garay

holds a degree in Literature and a Master of Arts from the Universidad de los Andes with an academic focus in Textiles. She is currently an Escuela de Artes y Oficios Santo Domingo student, pursuing a Technical Labor Certification in Embroidery. Her work focuses on the female body and its plastic form through textiles.

Noten

- Mol, Annemarie. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Duke University Press, 2002, pp. 33-34. ↩

- Rosner, Daniela K. Critical Fabulations: Reworking the Methods and Margins of Design. The MIT Press, 2018; Wajcman, Judy. Tecnofeminismo. Valencia, Ediciones Cátedra, 2006. ↩

- Sánchez-Aldana, Eliana. “(Un)crafting Ecologies: Actions Involving Special Skills at (Un)making Things Humans with Your Hands.” Ecological Reparation, ed. by Dimitris Papadopoulos, Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, and Maddalena Tacchetti, Bristol University Press, 2023, pp. 329-43. ↩

- Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble. Duke University Press, 2016, pp. 9-22. ↩

- Kim, Eugene Eric, and Betty Alexandra Toole. “Ada and the First Computer.” Scientific American, vol. 280, no. 5, 1999, p. 76. ↩

- Tabet, Paola. “Las manos, los instrumentos, las armas.” El patriarcado al desnudo. Tres feministas materialistas, ed. by Collete Guillaumin, Paola Tabet and Nicole Claude Mathieu, Brecha Lésbica, 2005, p. 68. ↩

- Harding, Sandra. “Is There a Feminist Method?” Feminism and Methodology, ed. by Sandra Harding, Indiana University Press, 1987; Mamidipudi, Annapurna, and Radhika Gajjala. “Juxtaposing handloom weaving and modernity: Building theory through praxis.” Development in Practice, vol. 18, no. 2, 2008, pp. 235-44. ↩

- Preciado, Beatriz. “Género y performance. 3 episodios de un cybermanga feminista queer trans...” Debate Feminista, vol. 40, 2009. ↩

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, Macmillan, 1988. ↩

- Harding; Mamidipudi and Gajjala. ↩

- Sánchez-Aldana, Eliana. Destejiendo/tejiendo ausencias: coreografías textiles que destejen/ tejen cuerpos individuales y colectivos. Doctoral dissertation, Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2023, p. 30. repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/83333. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024. ↩

- Pérez-Bustos, Tania, and Sara Márquez. “Destejiendo puntos de vista feministas: reflexiones metodológicas desde la etnografía del diseño de una tecnología.” Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencia Tecnología y Sociedad, vol. 10, no. 31, 2016, pp. 1-18. ↩

- Braidotti, Rosi. Feminismo Posthumano. Barcelona, Gedisa, 2022, p. 123. ↩

- Ingold, Tim. “Materials against materiality.” Archaeological Dialoguesi, vol. 14, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-16. ↩

- Zafra, Remedios. (h)adas: Mujeres que crean, programan, prosumen, teclean. Málaga, Páginas de Espuma, 2016, p. 10. ↩

- Plant, Sadie. Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture. 4th Estate, 1998, p. 5. ↩

- Kim and Toole, p. 76. ↩

- Berlinski, David. The Advent of the Algorithm: The Idea that Rules the World. New York, Harcourt, 2000. ↩

- Barad, Karen. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs, vol. 28, no. 3, 2003, pp. 801-31. ↩

- Díaz Dangond, Laura. Metatextil: Tejiendo mi ser tejedora. Universidad de los Andes, 2022; Sánchez-Aldana, 2024, p. 6. ↩

- Sánchez-Aldana, 2024. ↩

- Zafra, p. 31. ↩

- Grijelmo, Álex. La Seducción de las Palabras. Mexico, Santillana, 2000, p. 177. ↩

- Haraway, 2016, pp. 10-30. ↩

- Suchman, Lucy. “Subject objects.” Feminist Theory, vol. 12, no. 2, 2011, pp. 119-45. ↩

- Rosner, 2018. ↩

- Haraway, Donna. Manifiesto Ciborg. 1984, pp. 251-311, webs.uvigo.es/xenero/profesorado/beatriz_suarez/ciborg.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024. ↩