Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 28 nr. 2, pp. 4-17

Leren van precariteit. Kan de cocktail van crisis, precariteit en verbeelding de broodnodige fundamentele veranderingen teweegbrengen in de kunsten?

Louise Vanhee

Triggered by the course ‘The Arts in Times of the Corona Crisis’, Louise Vanhee started exploring the cultural difference between Belgium and The Netherlands in their appreciation of and support for the arts sector, before and during the corona crisis. In this essay, she tries to establish the main differences, as well as making a plea for a basic income system in the arts.

Naar aanleiding van het vak ‘The Arts in Times of the Corona Crisis’ is Louise Vanhee op zoek gegaan naar de culturele verschillen in het waarderen en ondersteunen van de kunstensector in België en Nederland, voor en tijdens de coronacrisis. Met dit essay probeert ze deze verschillen te achterhalen en voert ze een pleidooi voor een basisinkomen in de kunst.

The arts sector was in a precarious state long before covid-19 broke out. Job insecurity, low or no wages, fluctuating funding and alternating government attitudes towards the sector have caused artists to get used to living in a constant state of precarity. Therefore, this essay will explore what precarity, crisis and imagination mean for the arts sector. It will examine to what extent these notions, intrinsically connected with the sector itself, are capable of producing change for the sector — and for society as a whole. Starting with a reflection on the three notions of crisis, precarity, and imagination in relation to the current state of the arts sector, this essay will argue why they might be the ingredients of a ‘perfect storm’. A perfect storm consisting of all the necessary elements that could produce a lasting institutional change in the arts sector. Next, this essay will delve into the precarious state of the arts and the artist in two neighbouring countries: Belgium – and more specifically Flanders – and the Netherlands. This essay will look at the social, cultural, and political differences between the Netherlands and Flanders in how they value and fund the arts and how they handle relief funds for the arts sector during the corona crisis by examining the immediate responses to the crisis in a time frame from March until July 2020. Finally, this essay will examine whether the current crisis – and subsequent ‘perfect storm’ – can revive the debate on a basic income, and argue why the arts sector is an ideal place to experiment with this.

© Frederik Beyens

The perfect storm

We are in the midst of a global crisis. This is evident and undeniable. A crisis of this scale that affects virtually every single person on the planet is a historical first. Whilst the pandemic has separated people and forced most to stay in their homes and in quarantine, it has also connected people from all over the world who are experiencing strikingly similar issues. The social distress of quarantining, the economic uncertainties of access to basic amenities but also to financial security, and most of all, an unforgiving, indiscriminating virus that can affect any community, any family, any person, and which has in some shape or form, created a shared experience of crisis.

German historian Reinhart Koselleck provides us with a historical and etymological reading of the word crisis.1 The word crisis finds its origin in ancient Greek with various meanings attached to it: to ‘separate’ (part, divorce), to ‘choose’, to ‘judge’, to ‘decide’, ‘to quarrel’, or ‘to fight’.2 After examining various historical events in which the word crisis was used, Koselleck sums up four interpretative possibilities: crisis can mean (1) ‘a chain of events leading to a culminating, decisive point at which action is required’; (2) ‘a unique and final point, after which the quality of history will be changed forever’; (3) ‘a permanent or conditional category pointing to a critical situation which may constantly recur or else to situations in which decisions have momentous consequences’; or (4) ‘a historically immanent transitional phase’.3 Looking at these four possibilities, what makes something a crisis is quite clear. Crisis has to do with a critical moment that challenges a person or a specific group of people, and requires them to make a decision. In this respect, change can be longed for, and worked towards for a long time, but nothing will help it occur faster and more impactful than a crisis.

In response to the current crisis, activist and author Naomi Klein pleaded for ‘transformative change amid coronavirus pandemic’.4 The author of the bestseller The Shock Doctrine (2007) warned about the dangers of rash political decisions taken while the population is in a state of shock, disorientation, and panic due to some kind of crisis, long before the corona pandemic broke out. Times of crisis can be used to enhance the fortune of the richest corporations and to make dubious political decisions, while the rest of the country is still dazed and confused in the midst of the crisis. People in power will attempt to push ideas to their benefit which previously seemed too outlandish, but now in a crisis atmosphere might pass. Klein refers to one of Milton Friedman’s famous quotes: ‘Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.’5 She argues that the same tactic should be used by others — those with ‘good’ intentions — as they also have a stack of ideas lying around that could now finally be implemented. Radical ideas often characterized as utopian or delusional might now seem more feasible.

It is important to be aware of the power a crisis might generate, and although it can devastate many lives, we must be prepared to fully take advantage of a crisis when it comes around. Equally, Dutch author Rutger Bregman reflected on the financial crisis of 2008 in his book Utopia for Realists (2016), and wondered whether ‘the cognitive dissonance from 2008 was even big enough [to produce real change]’.6 The term cognitive dissonance is used to describe a situation where people are confronted with two conflicting values or beliefs. People can sometimes be unaware of the exact situation that is causing their discomfort, or choose to ignore it intentionally. Other times, the cognitive dissonance is so big it becomes impossible to ignore, and that is when real change can occur. It is this exact moment of realization Bregman looks back on. He wonders why, despite the severity of the situation on Wall street, no real change or reform occurred in the global bank sector. Was the crisis not big enough, or was it too big? The most frightening diagnosis according to Bregman is that perhaps ‘there were simply no alternatives’. He, too, reflects on the Greek origin of the word crisis: ‘A crisis, then, should be a moment of truth, the juncture at which a fundamental choice is made. But it almost seems that back in 2008 we were unable to make that choice. [...] Perhaps, then, crisis isn’t really the right word for our current condition. It’s more like we’re in a coma. That’s ancient Greek, too. It means “deep, dreamless sleep”.’7

The current global pandemic is a crisis of a different nature than the one of 2008. Although both had – and still have – devastating economic effects, the current crisis has much more pervasive consequences on society as a whole, magnifying the already existing precarity of certain people and sectors to an unbearable scale. This is particularly evident in the arts sector, and one can wonder if the cognitive dissonance is finally intense enough now to produce real change, and what alternatives we have to address the precarity of the arts sector.

The corona pandemic has highlighted how precarious much of our social, physical, and economic existence really is. The world has been taken by surprise by a virus that can affect anyone, and that can be passed on at a dangerously high rate, forcing most of the world into some sort of quarantined and restrained version of their normal life. Job security is not guaranteed for most and the economic backlash of the global lockdown will remain palpable and have ruthless consequences for many years to come. Simple things people had taken for granted, such as the freedom to leave their own house when they pleased, seeing family and friends, going for a drink, etc., have now taken on a whole new meaning. Precarity is the word that has defined and shaped this time of crisis and will remain relevant for the foreseeable future. While precarity is most often used in reference to job security, it is now also understood in relation to other elements, such as the insecurity and unpredictability concerning physical freedom, maintaining social relationships, and health security and care.

While the whole world is adjusting to this ‘new normal’, and governments are struggling to find funding to keep affected sectors and citizens of the crisis afloat, one sector — often overlooked and dismissed during this crisis — could provide much more answers than one might assume, namely the arts sector. It is a sector that would probably be categorized by many as being one of the least crucial sectors during these times of crisis, yet many facts dispute this brash statement. People — especially during times of crisis — have an inherent need for culture, arts, and humanities to help make sense of it all. The social connection the arts provide was greatly underestimated and underappreciated, but has now proven to be sorely missed during the lockdown. The arts sector has rallied and adjusted — much quicker than some sectors — and provided innovative and alleviating alternatives to engage with culture and arts for people to experience in the comfort and safety of their own home.

Perhaps one of the reasons the arts sector was so quick to adjust is because precarity is a fundamental aspect of the arts society. Most artists are no strangers to economic insecurity and uncertainty; finding creative and flexible solutions to make ends meet is a modus vivendi for them. Many artists have a precarious lifestyle in which they produce and create despite constant job insecurity and welfare issues. They take jobs that pay, but that they are less passionate about, to be able to invest in the ones that do give them the artistic freedom and satisfaction they are looking for. They combine multiple jobs, most of which are not necessarily in the arts sector itself, which gives them the liberty to express themselves artistically. Their work is not easily quantifiable in hours or worth. It also questions traditional conceptions of work, which draw upon a clear-cut difference between working hours and free time. As Thomas Decreus and Christophe Callewaert put it: ‘The more creative the job, the harder it becomes to distinguish work from free time. When does a writer stop writing? When does a scientist stop thinking about his work? Or when does a designer stop designing? Frankly, never.’8

The idea of the starving artist has been around for centuries, and probably will remain in the minds of the general population. It seems as if precarity and the arts go hand in hand. But one can wonder if they really should be so intertwined, or at the very least what the limit to precarity is. The current crisis has proven that the level of precarity present in the arts sector, has become unbearable and unsustainable. Furthermore, the crisis has made it clear to everyone what it is to live precariously. Judith Butler outlined the difference between precarity and precariousness – precarity being a politically induced condition of societal and economic disparity, and precariousness as an inherent aspect of human vulnerability.9 It is exactly this awareness of precariousness – that we are all equally vulnerable – this crisis has shown us. Moreover, this realization should open our eyes to already existing states of precarity. It should encourage us to imagine a society in which precarity is not an inherent aspect of someone’s life or of an entire sector.

Dear imaginary you,

This is a letter to many appearances and embodiments of you, whom I missed so dearly. Imagining is a rewarding task, but only if it is done together, collectively, as a process and a practice which happens from below and in the middle of the differences between us.10

These were the opening lines of an open letter written by Bojana Kunst, philosopher and contemporary art theorist. It was addressed to ‘the performance artist’ specifically, but in general to all those suffering in the arts sector due to this crisis. She thanks the artists for their care during the crisis and lockdown, comparing them to health care workers, as they ‘in a more poetic way’ invented ‘expressions, choreographies, and situations of care’.11 Imagination is at the core of the arts, and is what has attracted people to the arts since the beginning of humankind. Arts and culture not only try to make sense of society, and act as a reflection of the society from which they stem, they often transcend societal differences and create bridges between a variety of people.

Just like the global crisis has given everyone a shared experience of suffering, pain, and sorrow, so has the arts during this crisis provided relief, happiness, and distraction on a global scale. Despite the precarity of their situation — financial, emotional, and physical —, artists around the world have rallied and adapted to the crisis. Museums went online, artists from all over the world performed together in live streamed shows, designers helped to create solutions for the 1.5 metre rules... Even if one just listened to the radio, read a book, or watched tv, the arts and culture sector has provided relief — or as Kunst describes it: ‘care’ — to millions of people all over the world. But Kunst goes further in her letter. She delves into what this crisis has taught us about care, and more specifically the ‘right care’. That ‘right care’ is now found in distancing from one another as an act of solidarity, preventing artists to perform and care for society in the ways they normally do. But what about the care society has – or should have – for the arts?

This crisis has proven some things don’t work at all and need a change; change on a social, economic, financial, political... level. But also change in the arts, as it has become clear there is a limit to the amount of precarity the arts can handle. American art critic Jerry Saltz stated that ‘art will vanish only when all the problems it was invented to explore have been explored. [...] Creativity was with us in the caves; it’s in every bone in our bodies. Viruses don’t kill art. But even successful artists will be pushed to the limits, let alone the 99% of artists who always live close to the edge.’12

It seems as if the change a crisis can produce isn’t always guaranteed to last, or to be considered as positive in most regards. Nor is precarity alone enough to elicit viable changes. Good ideas, plans and initiatives need to be ready for when that crisis occurs, especially if it occurs in an already precarious situation. Imagination is a crucial ingredient to effectuate lasting change in times of crisis. A hefty dose of imagination is necessary to create and implement change that can act as more than just a simple plaster for a problem or a crisis, but initiate real institutional, cultural, political, social... change. To dare to dream, not in the comatose sense Bregman mentioned, but in a daring, bold, creative — and dare we say, artistic — way. That is why the arts sector is not only a sector in dire need of change due to this crisis (and long before the crisis), but it is also the sector from which the most imaginative change can emerge and originate.

The precarious nature of the arts

It goes beyond the scope of this essay to map all the funds, rules, and bureaucracy surrounding the arts sector, before, during, and after the crisis, in the Netherlands and Belgium. However, to understand how we as a society care for the arts, it is interesting to look at specific rules and regulations in the arts to give an idea of the cultural, social, and political attitudes of both countries towards the sector. If the research into this matter has taught me one thing, it is that the idea that we can bureaucratize and govern the creative sector and adjust the multitude of different work situations to fit existing structures and administrative boxes, is unrealistic. The inaccessibility and obscurity of many of the governmental sites aimed at supporting artists is telling. It is not hard to imagine that people miss out on profiting from existing benefits and subsidies, due to the lack of transparency and the overwhelming administrative burden. Therefore, it is neither my claim nor goal to give a detailed overview of the arts and cultural sector in both countries, and perhaps my inability to do so, exemplifies the shortcomings of the bureaucracy of the sector.

In Belgium, there is a remarkable thing called an ‘artist status’. What makes it remarkable is the fact that legally there is no such thing as an ‘artist status’. You can either have a status as self-employed, an employee, or as a civil servant. The entire social welfare system is based on these different social statuses and the category you belong to will greatly impact your unemployment benefits and social taxes. Most differences are found in the status of self-employed or employee, as you either work for someone or you work independently. How then does the artist fit into this binary model? Nowhere apparently, hence the creation of the fictitious ‘artist status’. I say fictitious because the term ‘artist status’ could easily lead to misconceptions. ‘The artist’s statute is not a fourth social status (in addition to employee, self-employed or civil servant), but a collective term to encompass all the measures that allow artists to have access to the system of social security and unemployment.’13 As artists will often work for someone — create, perform, build etc. — for a short period of time, they are considered employees, but they don’t have anyone telling them how to perform their function and have complete independence in their work, which is what makes them employers or self-employed. The ‘artist status’ consists of a number of social benefits that attempt to help balance out the equilibrium of both statuses and aims to ensure the artist is not left with the negative burdens and obligations of each status.14 For example, unemployment benefits will not go down in time. In that sense, artists can have some sense of financial security when there is a period in which they have less job opportunities.

In order to determine who qualifies as an artist, the definition was more or less based on the basic rules of copyright. Any person engaged in ‘the creation and / or performance or interpretation of artistic oeuvres in the audio-visual and visual arts, in music, literature, spectacle, theatre, and choreography’ provides an artistic performance and is therefore entitled to access to the artist statute.15

This of course all sounds very good and appealing but bear in mind that the road to the ‘artist status’ is not an easy one, and if you forget to fill in your pile of paperwork every year, you will lose it. Each ‘artistic activity’ you perform for someone must be registered with your social bureau before it takes place. Each day you ‘perform’ must be noted on your ‘control card’ for unemployment benefits. If you work according to a ‘task wage’ instead of an ‘hourly wage’, and want to combine this with unemployment benefits, you will be required to hand in a form and your ‘control card’ to the social bureau every month. The general rule of thumb is that you have to be able to prove you have worked 312 days over a period of 21 months, to be eligible to apply for the ‘artist status’. Given the flexible nature of the work an artist does, planning and managing all of this often becomes a job in itself.

Comparison of the ‘artist visa’ (top) and the ‘artist card’ (bottom) © Artists United.

The Artist Committee founded in 2002, consisting of twelve Dutch-speaking representatives and twelve French-speaking representatives, is responsible for deciding who can benefit from the ‘artist status’ and who cannot. They also have the power to grant applicants with two additional forms of benefits: the ‘artist card’ and the ‘artist visa’. The first allows the artist to benefit from the KVR [Small Compensation Arrangement], meaning they would not have to register or pay taxes on small artistic jobs. The second allows the artist to enjoy the benefits that are associated with being an employee, without having to commit to an employee contract with an employer.16 (Comparison of the ‘artist visa’ and the ‘artist card’).17

One can wonder what the reasonings are for separating the benefits of the two cards, or why there is a need for the two separate cards – which look identical – in the first place. To receive either one of the cards, an almost identical procedure must be followed in which artists must prove the ‘artistic nature’ of their activities. The guidelines for applying for both the visa and the card answer the question ‘what recommendations should be followed when I submit my application?’ with exactly the same twelve steps.18 Not surprisingly, Artists United, an independent advocacy and consultancy group for the arts sector, responded to this issue with: ‘Welcome to the wonderful Kafkaesque Belgian regulations.’19

The Netherlands has a different approach towards the arts sector in comparison to Belgium. Whereas Belgium offers a lot of different types of security and benefits — even though they are hard to obtain, maintain, or actually work with —, the Dutch approach is one that fosters more independence and self-reliance. An artist is considered an entrepreneur and is responsible for ensuring he can live and profit from his work. Recent studies, such as Capturing Value by Creatives. How to Unite the Cultural and Entrepreneurial Soul (2019), show the importance of the entrepreneurial approach. Emphasis is placed on the financial literacy of artists and how ‘one can create creative and artistic quality and at the same time safeguard the economic survival of the venture.’20 Whereas in Belgium you will find an abundance of SBKs, in the Netherlands these are replaced by ‘knowledge centres for entrepreneurship in the cultural sector’, such as Cultuur + Ondernemen. They offer advice and courses to artists and entice them with slogans like ‘successful entrepreneurship can make the difference between survival and a sustainable future’ and ‘Entrepreneurship route: Increase your chances in 8 steps. Business guide for artists and creatives’.21 This does not mean, however, that everyone in the arts sector is an entrepreneur. Most have an independent status called ZZP [Self-employed Without Employees], which can be compared to working as a freelancer. This can be considered similar to the ‘artist status’, apart from the fact that there are little to no forms of social security, unemployment benefits, or pension building. While some will consider being a ZZP equal to being an entrepreneur, that opinion is not shared by many, as the choice to become a ZZP is often made out of necessity due to the scarcity of permanent jobs in the arts sector. Over 70% of people active in the cultural sector is a ZZP.

There used to be a sort of social safety net in the Netherlands similar to the ‘artist status’ in Belgium, called the WWIK [Work and Income for Artists Bill]. The law was abolished in 2012, after being implemented only in 2005, and offered artists the possibility to supplement their income for a maximum of four years, spread out over ten years, if they could not support themselves with their artistic practice. The reasoning behind the decision was that

the cabinet sees artists as cultural entrepreneurs who do not just create art. The new subsidy policy is aimed at stimulating artists to provide their own income. According to current cabinet policy, artists are also entrepreneurs who have to market their product and want to reach a large audience. The cabinet therefore wants to stimulate cultural entrepreneurship. In line with this, the WWIK will be abolished and the number of subsidies limited.22

Although the abolishment of the law faced harsh criticism and protests from artists who feared ending up in poverty, others had pleaded for the ending of the law years before the government made the decision. In 2010, Dutch philosopher Sebastien Valkenberg argued in a column that the WWIK should actually be considered a negative thing, reaffirming the archaic notion that precarity and the arts go hand in hand.

Actually, you should avoid the WWIK just because of the image damage it causes. Doesn’t anyone who considers him/herself a little bit artistic prefer the bohemian existence at the edge of society? Where is the artist who, in the spirit of Willem Kloos, cherished his poverty? This deprivation may be a nuisance, but it is also a virtue, or a hallmark if you like. Certainly in the late nineteenth century it was seen as the visible proof of artistic freedom. Surely, the artist will not allow him/herself to be sustained by the same society that s/he is supposed to be judging and disrupting?23

There is a clear cultural dissonance between the Netherlands and Belgium, with the one romanticizing the independence and freedom of the artist regardless of the lack of financial or social security, and the other attempting to provide safety nets for artists that come with rules and regulations that are often deemed inaccessible or incomprehensible. In an article published soon after the abolishment of the WWIK, artists from the Netherlands and Belgium debated the cultural differences in their sectors. Whereas Belgian artist Tom Struyf felt that the ‘artist status’ provides freedom to create what ‘really matters’, instead of ‘being forced to participate in things that are of no interest [to the artist]’, Dutch artist Freek Vielen was hesitant to ‘receive a certain amount regardless of what you have achieved [artistically] that month.’24

In the Netherlands, entrepreneurship is much more deeply ingrained in the DNA of everyone involved in art. In Flanders, the importance of culture seems to be much more a given for any healthy society. Culture is something that also has a right to exist outside of a strictly economic reality.25

Is either of the approaches really suitable to support artists, or are they just two variations on the same theme — one toddler forcing a square peg into a circular hole, the other trying out the triangular peg?

When the debate turned to what the effect of this different approach is on the quality and character of theatre in both countries, Struyf argued that the entrepreneurial approach of the Netherlands resulted in a ‘more professional business that employed people with clear qualities and capacities’, whereas in Belgium you could ‘do really strange things and still be taken seriously.’26 In the article, dating back to 2012, the artists wondered if this liberalization of the labour market, with its entrepreneurial character, that exists in the Netherlands would take over Belgium any time soon. A recent publication by Kunstenpunt ’92 (2020) reflecting on the status of the ZZP, showed the cultural dissonance between both countries is still quite strong. Flemish author, journalist and screenwriter Gaea Schoeters argued that the Dutch entrepreneurial way of working should be avoided as much as possible:

I already find the whole idea of an artist as an entrepreneur very strange. An artist has to make art. I don’t want to spend eighty percent of my time on a business model, raking in subsidies, and financing a ‘product’. This line of thought is not only disastrous for art, it concerns all areas of life. Actually, it is not at all the job of an artist to solve such problems. [...] Financial return is not the role of art. The ‘return’ that you get from art is, in the first place, social gain. Art has a role as a critical barometer of society, to reflect on that. It doesn’t have to generate money at all.27

The opacity of the artist status and its benefits in Flanders, and the self-reliant entrepreneurial approach in the Netherlands both clearly have its advantages and disadvantages. Is either approach really suitable to support artists, or are they just two variations on the same theme — one toddler forcing a square peg into a circular hole, the other trying out the triangular peg? Their differences have proven that neither one of the approaches is sufficient in addressing the needs or understanding the nature of the arts sector, and the corona crisis has only exacerbated the already existing issues and problems.

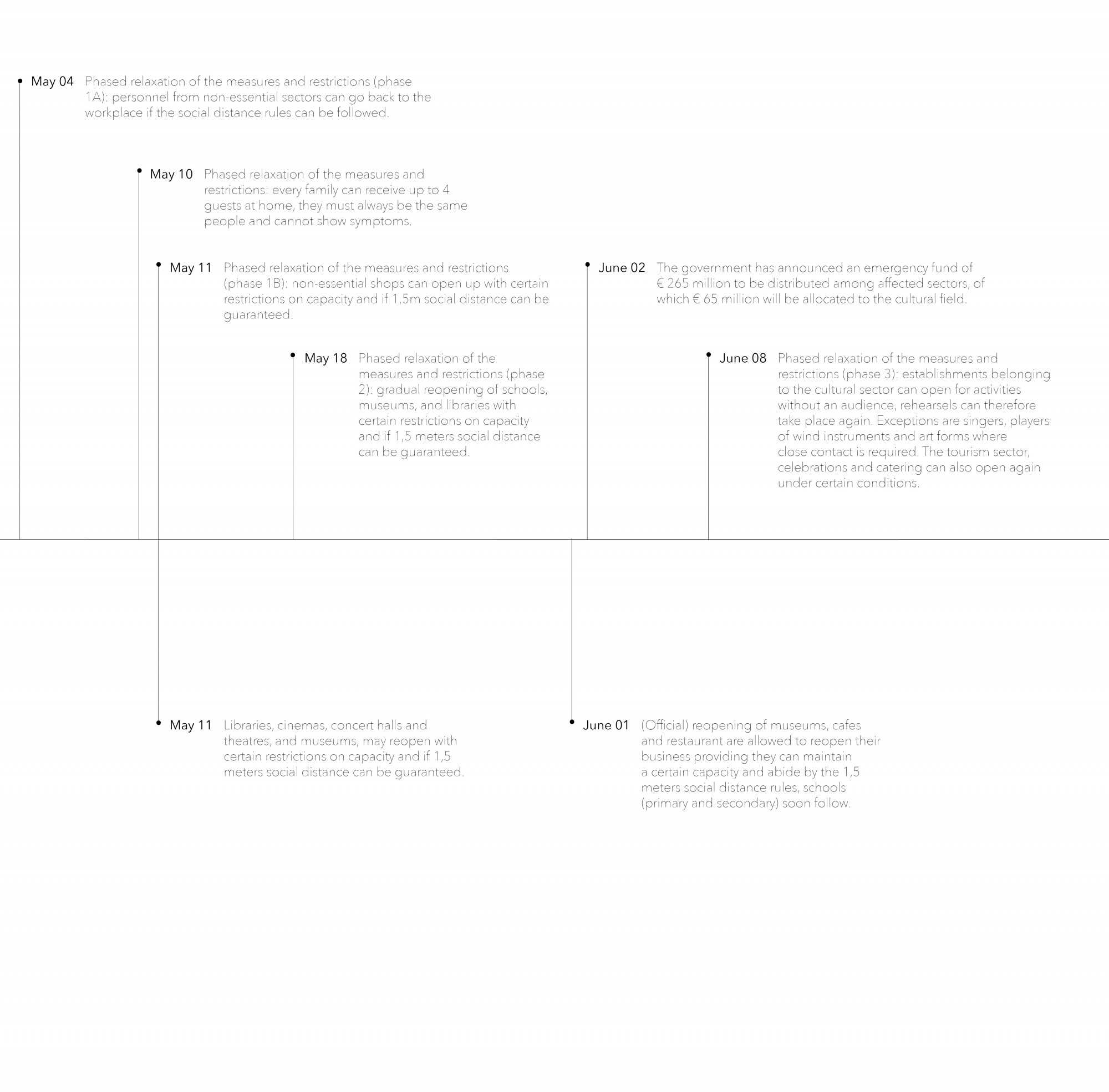

The corona crisis

Both countries have had similar responses to the crisis and comparable timelines. However, Belgium’s stricter enforcement of a lockdown and continuing second wave, have resulted in a slower reopening of certain sectors, and tougher rules in the events sector. At the beginning of the crisis, both governments implemented a series of general relief measures intended to support entrepreneurs and businesses. The most noteworthy relief measures taken in the Netherlands are the NOW [Emergency Bridging Measure for Employment], TOGS [Entrepreneurs Allowance Affected Sectors COVID-19] and TOZO [Emergency Bridging Measure for Self-employed].28 Yet, it immediately became apparent that some of these relief measures could not be accessed by the arts sector. TOGS caused problems as it excluded certain cultural institutions if the company did not fall within a selection of so-called SBI codes [Standard Industrial Classification]. Moreover, the address of the company may not correspond to the home address of the person applying for financial support. The issue with TOZO was that it was only available for someone with a ZZP status that met the criterion of at least 1,225 hours per year. An open letter was sent to the government on 27 March 2020, by the Dutch Minister of Culture, Education and Science Ingrid van Engelshoven, in which she pleaded for more sector-specific relief measures. SBI codes of relevant cultural institutions and businesses were added to the list of the TOGS, and government-subsidized museums were given a rent suspension. The Minister hoped local municipalities and provinces would follow her lead and see what could be done for cultural institutions on a smaller and more local scale.29

Similar issues emerged with the Belgian general relief measures. Artists with permanent contracts — ergo, working fully as an employee — could fall back on temporary unemployment benefits consisting of 70% of their average salary. Fully independent artists, with a self-employed status, could rely on a variety of relief measures, including temporary exemption or reduction of taxes, a special ‘bridging’ regulation entitling the artist to full or partial unemployment benefits, a one-time ‘corona compensation premium’ for businesses (€ 3,000), etc. The problem, however, is that artists in Belgium are rarely permanently employed by someone else and often don’t have their own businesses. To access the ‘bridging’ regulation for self-employed people for example, income scales were demanded that most independent artists never reach. Most also work with short-term contracts, which all fell through because of the pandemic. If these contracts were not registered at an SBK before 13 March, the artist didn’t have the right to any form of unemployment benefits related to that contract. Even people with the infamous ‘artist status’ found themselves falling between the cracks of the relief funds. To maintain the ‘coveted’ status, a minimum of 156 days has to be worked, spread over at least 18 months. Many artists now fear they are at risk of losing the status. All the rules and requirements surrounding the various relief measures contain small lettering at the bottom, which prohibits many people working in the arts sector to benefit from them.

No, it isn’t time to nit-pick about the details. Yet the testimonies prove exactly that these are not details: for many they make a difference between being able to pay the rent or not: a difference between getting a little and nothing.30

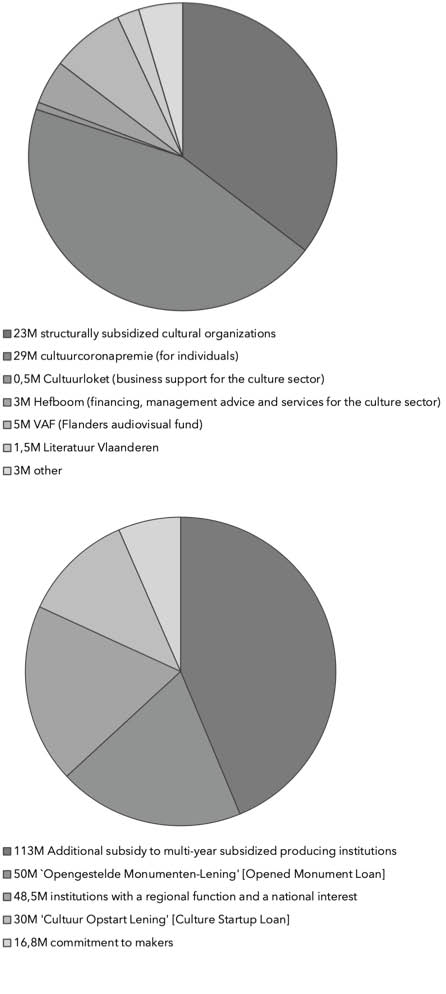

The lack of transparency in the Belgian system not only makes it very difficult for artists to know which benefits they can apply for, but the rules and regulations are constantly changing and often late in offering the much-needed financial relief. The unforeseen severity of the pandemic and consequential lack of perspective are definitely big contributors, but the real issue is that this system simply does not correspond with the realities of working in the arts sector, resulting in many cultural and creative workers being left behind. (The Netherlands — 300 Million for Culture,31 Belgium — 65 Million for Culture).32

Belgium (top) - 65 Million for Culture, the Netherlands (bottom) - 300 Million for Culture.

Unlike the Netherlands, Belgium did not provide an immediate response to the shortcomings of the general relief measures, giving rise to a loud call for a ‘corona emergency fund’ for culture. Belgian art critic Wouter Hillaert gathered testimonies from various artists, organizations, and institutions in an article fittingly titled ‘The financial battlefield called corona’. Following the response of the Dutch government, he openly wondered ‘when will Flanders and/or Belgium follow?’33

When Belgium announced a second extension of the measures and restrictions on 15 April, the Dutch government announced they would provide an additional relief fund of 300 million euros for the arts and culture sector.34 After continuous public outcry,35 36 Flanders finally followed suit and announced a sector-specific emergency relief fund of close to 300 million euros.37 This fund, however, is intended not only for the culture sector, but also for the tourism, sport, youth, media, mobility, and agricultural sector. Therefore, only 65 million of that funding will go to culture. Of course, we have to take into account that Flanders is smaller than the Netherlands, but when comparing 65 million to the gigantic sum of money that the Netherlands is providing, one could wonder if the cultural dissonances in how the arts are valued and funded in both countries have shifted. Yet looking at both relief funds up close reveals that only a small portion of both funds will probably make it to the people at the end of the chain in the sector — those who need it the most, and have the most fragile and precarious statuses —: the freelancers, ZZPs, and self-employed artists. The distribution of the funding in Flanders will take place through the network of structurally funded organizations. The concern here is how the money will reach the freelancers, and especially how it will reach young artists who have not yet had the time to make connections with such organizations and institutions. Similar issues are apparent within the division of the funding in the Netherlands; a whopping 113 million is provided for established cultural institutions, while only a meagre 16,8 million will go to what is ambiguously referred to as ‘makers’. In comparison, Flanders promises 29 million as ‘corona premiums’ for individuals in the arts sector. Perhaps the romantic idea of the starving artist is still stronger in the Netherlands than it is in Belgium? A reader’s response to an article in which the Dutch Minister of Culture pleaded for more support for the arts sector, painfully showed the underappreciation of the sector:

Most overestimated and unimportant sector out there. Enough people who make a painting as a hobby, play as a DJ, perform a play, play a football match, etc. They can also have a job. Culture will continue to exist even if people earn little or nothing from it. Quality will indeed be lower than if you practise it full-time, but no one will notice. A football match of the amateurs or first division does not have to be less exciting and fun than the premier division if it concerns your own club. This is the case with the entire culture sector. If the economy is fluid, it is fine to put money into it, but it is not the first (read: it is the last) priority for me at the moment.38

The corona crisis has painfully revealed the shortcomings of the financial and social security of people working in the arts sector. Things aren’t working, and many people have lost wages, jobs, and future perspectives. As both the Netherlands and Belgium were forced to ban public events, arts and culture have become the most devastated sectors due to the crisis, with almost no relief in sight. The emergency relief funds for culture are a good start, but provide little comfort for the small artist, as it remains unclear how and if the individuals with the most precarious statuses of the sector will receive anything. Even if everything goes back to normal, this crisis has proven instrumental change is necessary to provide the arts sector with stability and support for the future. The relief funds are responses to the acute crisis and financial precarity the arts sector is in, but we have to make sure we take this opportunity to also think long-term. The manner in which we reshape the social, financial, and legal structures of the arts sector now – at a moment where it is most vulnerable – can be instrumental in inspiring future change for society as a whole.

A basic income for the arts

What could that necessary and instrumental change in the arts look like? How can we improve the social and financial security of the artist? How can we ensure the artist can focus on producing art and not on running a business? How can we de-bureaucratize funding and administration, and make it more transparent and accessible for artists?

Artist Salary Now, campaign work 2018 © Karin Hansson.

If you would ask Swedish artists Karin Hansson and Per Hasselberg, that change would come in the form of a basic income for artists. Starting from the rhetorical question, ‘Should we spend our time filling out forms or making art?’, Hasselberg, Hansson, and other artists held a series of events in September 2018 called Konstnärslön nu! [Artist salary now!].39 The ideas behind a basic income for the arts derive from the concepts found in the universal basic income or UBI. The social benefits of a basic income in the arts sector are huge: it improves the poor social security of the artist; allows artists to work towards a liveable pension; allows for easier establishment of young artists in the field who don’t have a lot of connections; allows for easier establishment in the field for older artists who find the digitization of networks and the sector in general, difficult to manage, etc. The practical benefits are also numerous. There would be less administrative work to maintain funding and grants. It could also result in decentralized organizations, with more transparency and diminished bureaucracy.40 In short, it sounds like the perfect solution, one that could even solve a lot of other issues in different sectors apart from the arts. Then why is no one pursuing this? (Artist Salary Now, campaign work 2018).41

The idea of the basic income — or universal basic income — has been around for quite some time. Daniel Raventós gives us a lengthy, but unambiguous definition of what a universal basic income is in his book Basic Income: The Material Conditions of Freedom (2007):

Basic Income is an income paid by the state to each full member or accredited resident of a society, regardless of whether he or she wishes to engage in paid employment, or is rich or poor or, in other words, independently of any other sources of income that person might have, and irrespective of cohabitation arrangements in the domestic sphere.42

The UBI has been tested, researched and discussed for decades. As Thomas Decreus and Christophe Callewaert argue in their book Dit is Morgen [This is Tomorrow] (2016), ‘the basic income is an idea that refuses to die. If the social debate is a garden, then the basic income is the weeds that are constantly growing in different places. Just when you think you have removed it from stem to root, it reappears.’43 The most important argument for a basic income is the idea of our current economic thinking and capitalistic society being outdated.44 In comparison with all the innovation and modernization we have achieved, the issue with how we work and why we work has been stuck in the past century. That is why Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams state in their book Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (2015) that ‘the most difficult hurdles for UBI – and for a post-work society – are not economic, but political and cultural: political, because the forces that will mobilise against it are immense; and cultural, because work is so deeply ingrained into our very identity.’45 There are many cultural connotations attached to work, resulting in people often immediately judging someone who is unemployed as being a person who is detrimental to society or profiting from the welfare system. Yet, work is being automated more and more, endangering more and more jobs. Why can’t we work a few hours less, and give someone without a job a chance? In response to the automation of productive jobs, we have created an endless number of administrative tasks that are becoming increasingly menial and trivial.46 How many teleworkers or corporate lawyers does society truly need? These types of jobs offer no real use or fulfilment, but they pay the bills. Doing something you love does not guarantee financial security, and that is a harsh fact artists are very much aware of. Most of them have chosen precarity over financial security to free themselves of the traditional concepts of ‘Fordist labour’. However, a UBI could ‘transform precarity and unemployment from a state of insecurity to a state of voluntary flexibility.’47 This flexibility would mean people have both the mental space and time to explore their interests and talents outside of what is expected in their job. Pilot studies have shown that when the stress and insecurity of providing for one’s basic needs is taken away, people are healthier and more productive.48

It is clear that the cultural connotations surrounding concepts of work are one of the biggest obstacles standing in the way of a UBI, yet the current global pandemic might have opened the door slightly for this debate to be held once more. Laura Basu reflected on this issue in a recent article titled ‘How to fix the world’:

We have been convinced that as a species we are incapable of creating good societies. But the idea that humans by nature are selfish and greedy, that we have insatiable needs, is a lie. Our needs are finite, satiable and unsubstitutable. The virus has taught us that. When given the opportunity, we want to help each other and contribute to the good of our communities. The virus has taught us that also.49

As many governments have provided emergency relief funds to ensure the survival of businesses and people in general, a reflection on why we work and how we work is ongoing. In Belgium, the government was at one point even paying the wages of over 65% of employees who were put on temporary unemployment, showing that the economic arguments of why a UBI would not work, need to be reviewed. New terminology such as ‘essential worker’ has also created new connotations in the way we think about work, and people seem to have learned how to be happier with less — less production, less consumption. In another recent article, author Shayla Love even went as far as wondering: ‘COVID-19 Broke the Economy. What If We Don’t Fix It?’50

‘Why the arts?’, an employee at the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science rightfully questioned when the argument of a basic income for arts was made. This is a difficult question, as the arts do not see themselves as more important or deserving than any other sector. On the contrary, Hasselberg and Hansson’s plea for an artist salary sees the salary ‘as a pilot for a future basic income, a salary that eventually will be for everyone, not only artists: a salary to allow for time to take care of our commons and existential issues.’51 If a UBI is to be experimented with in any sector — instead of being accepted as a concept for an entire society — one could argue that the arts is the best place to do so. A first reason is because the arts sector already has different connotations attached to what constitutes work. An artist rarely works the stereotypical nine-to-five hours and the relationship between produced value and hours worked/paid is the most liberal, flexible, and imaginative of all sectors. This means the cultural oppositions against a UBI would be easier to overcome in this sector than in any other sector. A second reason is the abundance of existing funding and grants in the arts sector — although they are not accessible to all. This could facilitate overcoming the economic oppositions for a UBI easier, as de-bureaucratizing the sector would even free up more money. A final reason why the arts sector should be a testing ground for a UBI is because they have proven themselves during this pandemic to be invaluable, comparable to other professions dubbed ‘essential workers’. During the lockdown, the arts provided us with relief from boredom, anxiety, and loneliness.52 The end of the current crisis is not yet in sight, and another one could be just around the corner. If we want to ensure that the arts can mentally help us through another lockdown, the time to act is now. People stating that the devastation of the arts sector is the least of their worries, have surely not tried removing tv, radio, books, visual art, etc., from their life and then quarantined for a long period of time.

Right now, the arts sector finds itself in the perfect storm — a storm made up out of crisis, precarity and imagination. It is a volatile combination, yet one that is perfect to cultivate and nurture real change.

Another remark by the employee at the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science, is that implementing a basic income for the arts differs from a universal basic income in one significant way, namely that it is not universal. One of the biggest powers of a UBI is that it doesn’t discriminate, hence it being called universal. A basic income for artists then has to define who is an artist and who isn’t. This problem understandably resulted in some scepticism. Yet, the strange and elusive ‘artist status’ in Belgium could serve as an inspiration to solve this issue. To receive this status, and other benefits like the ‘artist visa’ and ‘artist card’, one has to pass the Artist Committee and be ‘deemed worthy as an artist’. Although I have my own dose of scepticism about the committee, they do show that defining who is an artist and who isn’t, is not as impossible or implausible as one might think. Hasselberg and Hansson also propose a similar solution in the form of some sort of ‘peer review’, to ensure that people benefiting from the salary are deserving of it. Instead of bureaucrats deciding who is an artist and who is not, it would be artists themselves who are responsible for that decision. Artists would therefore no longer be dependent on government institutions, but on networks and relationships within the arts sector itself.

Learning from precarity

The cultural differences between the valuation and funding of the arts in the Netherlands and Belgium could create doubt, as it is clear the value and work of an artist bear different connotations in both countries. When asking a Belgian sculptor why he was opposed to a basic income, he stated: ‘Because I worked to ensure that I don’t need to rely on benefits, I proved my artistry.’ Yet, when asked whether his younger self would have refused an artist salary, and if perhaps he would have gotten to the point he is at in his career much faster with it, he hesitantly admitted it might be a good idea.53 This conversation showed that changing the mindset of people is difficult, and changing anything in the arts sector on an institutional level, even harder. Yet, the global pandemic has provided an opportunity to alter the current reality of the arts. Right now, the arts sector finds itself in the perfect storm — a storm made up out of crisis, precarity, and imagination. It is a volatile combination, yet one that is perfect to cultivate and nurture real change.

For us today, it is still difficult to imagine a future society in which paid labour is not the be-all and end-all of our existence. But the inability to imagine a world in which things are different is only evidence of a poor imagination, not of the impossibility of change.54

Abbreviations

Belgium

KVR Kleine Vergoedingsregelingen [Small Compensation Arrangement]

SBK Sociaal Bureau voor Kunstenaars [Social Bureau for Artists]

RVA Rijksdienst voor Arbeidsvoorziening [National Employment Service]

RSZ Rijksdienst voor Sociale Zekerheid [National Social Security Service]

RSVZ Rijksinstituut voor de Sociale Verzekeringen der Zelfstandigen [National Social Ensurance Service for Self-employed]

The Netherlands

NOW Noodmaatregel Overbrugging voor Werkgelegenheid [Emergency Bridging Measure for Employment]

TOGS Tegemoetkoming Ondernemers Getroffen Sectoren COVID-19 [Entrepreneurs Allowance Affected Sectors COVID-19]

TOZO Tijdelijke Overbrugging Zelfstandig Ondernemers [Emergency Bridging Measure for Self-employed]

ZZP Zelfstandige Zonder Personeel [Self-employed Without Employees]

WWIK Wet Werk en inkomen Kunstenaars [Work and Income for Artists Bill]

SBI Standaard Bedrijfsindeling [Standard Industrial Classification]

+++

Louise Vanhee

is afgestuurd als burgerlijk ingenieur architect aan de universiteit van Gent, en volgt nu een research master in kunst en cultuur aan de Rijksuniversiteit van Groningen. Haar onderzoek is gefocust op de relatie tussen kunst en architectuur.

Noten

- Koselleck, Reinhart, and Richter Michaela W. “Crisis.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 357-400. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Klein, Naomi, and Goodman Amy. “‘Coronavirus Capitalism’: Naomi Klein’s Case for Transformative Change Amid Coronavirus Pandemic." Democracy Now!, 19 March 2020, www.democracynow.org/2020/3/19/naomi_klein_coronavirus_capitalism, last consulted on 10 May 2020. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Bregman, Rutger. Utopia for Realists (Gratis geld voor iedereen: en nog vijf grote ideeën die de wereld kunnen veranderen). The Correspondent, 2016. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Decreus, Thomas, and Callewaert, Christophe. Dit is morgen. EPO, 2016. ↩

- Butler, Judith. “Precarious Life, Grievable Life.” Frames of War. Verso, 2009, pp. 1-32. ↩

- Kunst, Bojana. “Lockdown Theatre (2): Beyond the time of the right care: A letter to the performance artist.” Schauspielhaus Journal, 21 April 2020, www.neu.schauspielhaus.ch/en/ journal/18226/lockdown-theatre-2-beyond-the-time-of-the-right-care-a-letter-to-the-performance-artist, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Saltz, Jerry. “The Last Days of the Art World... and Perhaps the First Days of a New One. Life after the coronavirus will be very different.” Vulture, 2 April 2020, www.vulture.com/2020/04/how-the-coronavirus-will-transform-the-art-world.html, last consulted on 24 April 2020. ↩

- “Het kunstenaarsstatuut.” VI.BE, 16 January, vi.be/advies/de-kunstwerkuitkering, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- “Het kunstenaarsstatuut.” Cultuurloket, July 2018, www.cultuurloket.be/kennisbank/sociale-statuten/kunstenaarsstatuut, last consulted on 18 July 2020. ↩

- “Het kunstenaarsstatuut.” VI.BE, 16 January, vi.be/advies/de-kunstwerkuitkering, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- “Artist@Work.” Artist@Work, www.artistatwork.be/nl, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- www.artistsunited.be/nl/content/statuut-kunstenaarskaart-en-kunstenaarsvisum-p. ↩

- “Kunstenaarsvisum.” Artist@Work, www.artistatwork.be/nl/faq/kunstenaarsvisum, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- “Kunstenaarskaart is niet hetzelfde als kunstenaarsvisum.” Artists United, www.artistsunited.be/nl/content/statuut-kunstenaarskaart-en-kunstenaarsvisum-p, last consulted on 24 July 2020. ↩

- Hogeschool van Amsterdam, HKU University of the Arts Utrecht & Cultuur + Ondernemen. “Capturing Value by Creatives. How to unite the cultural and entrepreneurial soul.” HVA, 2019, www.hva.nl/binaries/content/assets/subsites/kc-be-carem/capturing-value-by-creatives-final-public-report-v141119.pdf, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- “Entrepreneurship route: Increase your chances in 8 steps. Business guide for artists and creatives.” Amsterdam. Cultuur+Ondernemen, May 2018, www.cultuur-ondernemen.nl/storage/media/ALG-20150507-CO-Business-Guide.pdf, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- “WWIK uitkering kunstenaars afgeschaft, kunstenaars moeten gaan ondernemen.” Fondswerving Online, www.fondswervingonline.nl/nieuws/wwik-uitkering-kunstenaars-afgeschaft-kunstenaars-moeten-gaan-ondernemen, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- Valkenberg, Sebastien. “Waarom is de WWIK zo slecht?” Trouw 23 December 2020, www.trouw.nl/nieuws/waarom-is-de-wwik-zo-slecht, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- Cleppe, Birgit, and Rummens, Tom. “Twee artistieke culturen in vogelperspectief — ‘Niet alles wat wij doen is meetbaar’.” De Groene Amsterdammer, 20 November 2012, www.groene.nl/artikel/niet-alles-wat-wij-doen-is-meetbaar, last consulted on 18 June 2020. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- van Ommeren, Miriam, and Tchong, Jaïr. “Ondernemerschap als Duizenddingendoekje.” Zzp’ers in de cultuursector, Kunsten ’92, February 2020, pp. 16-18. ↩

- Brom, Rogier, and Schrijen, Bjorn. “Hoe komt de cultuursector uit de corona-crisis?” Boekman,16 April 2020, www.boekman.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Hoe-komt-de-cultuursector-uit-de-coronacrisis-Volledig-16-april.pdf, last consulted on 16 June 2020. ↩

- “Maatregelenpakket cultuursector: huur rijksmusea opgeschort met drie maanden.” Rijksoverheid, 27 March 2020, www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/27/maatregelenpakket-cultuursector-huur-rijksmusea-opgeschort-met-drie-maanden, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- Hillaert, Wouter. “Tussen de mazen van het vangnet: cultuurwerkers getuigen.” Rekto:Verso, 15 April 2020, www.rektoverso.be/artikel/the-financial-battlefield-called-corona, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- “Aanvullende middelen voor cultuursector uitgewerkt.” Rijksoverheid, 27 May 2020, www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/ministerie-van-onderwijs-cultuur-en-wetenschap/nieuws/2020/05/27/aanvullende-middelen-voor-cultuursector-uitgewerkt, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- “Metaoverzich kunsten n.a.v. Coronacrisis.” Kunstenpunt. 3 June 2020, wp.assets.sh/uploads/sites/4718/2020/06/Kunstenpunt_corona_metaoverzicht3-6-2020.pdf, last consulted on 17 June 2020. ↩

- Hillaert, Wouter. “The financial battlefield called corona.” Rekto:Verso, 21 March 2020, www.rektoverso.be/artikel/the-financial-battlefield-called-corona, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- “Aanvullende middelen voor cultuursector uitgewerkt.” Rijksoverheid, 27 May 2020, www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/ministerie-van-onderwijs-cultuur-en-wetenschap/nieuws/2020/05/27/aanvullende-middelen-voor-cultuursector-uitgewerkt, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- “Een covid-19 noodfonds voor de culturele sector!” State of the Arts, state-of-the-arts.net/covid-19-noodfonds, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- “Noodkreet van cultuurwereld: ‘We hebben geen vooruitzicht op herstel’.” De Standaard, 5 May 2020, from: www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20200511_04954519, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- Willems, Freek. “Vlaamse regering verhoogt noodfonds tot bijna 300 miljoen euro: 65 miljoen gaat naar cultuursector.” Vrt, 2 June 2020, www.vrt.be/vrtnws/nl/2020/06/02/vlaamse-regering-verdeling-noodfonds, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- A reader’s (Matijs) response to “Van Engelshoven: Meer steun cultuursector nodig, alles redden onmogelijk.” NU, 29 June 2020, www.nu.nl/coronavirus/6061185/van-engelshoven-meer-steun-cultuursector-nodig-alles-redden-onmogelijk.html#coral_talk_wrapper, last consulted on 10 July 2020. ↩

- Hasselberg, Per. “How to fix the world.” Konstnärslön nu! (Artist salary now!), konstnarslon.nu, last consulted on 8 July 2020. ↩

- Hansson, Karin. “Artist’s Salary Now!” Parse, issue 9, Spring 2019, parsejournal.com/article/5992/?fbclid=IwAR3b044fOy9J, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- www.parsejournal.com/article/5992. ↩

- Raventós, Daniel. Basic Income: The Material Conditions of Freedom. Pluto Press, 2007. ↩

- Decreus, Thomas, and Callewaert, Christophe. Dit is morgen. EPO, 2016. ↩

- Srnicek, Nick, and Williams, Alex. Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. London, Verso, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Basu, Laura. “How to fix the world.” Open Democracy, 29 April 2020, www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/how-fix-world, last consulted on 8 July 2020. ↩

- Srnicek, Nick, and Williams, Alex. Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. London, Verso, 2015. ↩

- Standing, Guy. Piloting Basic Income as Common Dividends. London, PEF, 2019. ↩

- Basu, Laura. “How to fix the world.” Open Democracy, 29 April 2020, www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/how-fix-world, last consulted on 8 July 2020. ↩

- Love, Shayla. “COVID-19 Broke the Economy. What If We Don’t Fix It?” Vice, 16 June 2020, www.vice.com/en_us/article/qj4ka5/covid-19-broke-the-economy, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- Hansson, Karin. “Artist’s Salary Now!” Parse, issue 9, Spring 2019, parsejournal.com/article/5992, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- “Noodkreet van cultuurwereld: ‘We hebben geen vooruitzicht op herstel’.” De Standaard, 5 May 2020, from: www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20200511_04954519, last consulted on 24 June 2020. ↩

- The interviewed artist preferred to remain anonymous. ↩

- Bregman, Rutger. Utopia for Realists (Gratis geld voor iedereen: en nog vijf grote ideeën die de wereld kunnen veranderen). The Correspondent, 2016. ↩