Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 29 nr. 3, pp. 30-36

Ancestrale samenleefkracht. Hoe ik verliefd werd op queer diertjes

Risk Hazekamp, Nina Lykke

Nina Lykke and Risk Hazekamp found each other in their love of micro-organisms, especially Diatoms and Cyanobacteria. A warm digital exchange followed, both in words and images, in which the voices of Nina and Risk eventually merged into one shared ‘I’. A speculative, passionate conversation shaped up, investigating the precarious conditions of life and death on the planet, and figuring out pathways towards more joyful and ethical co-becomings with the planet body than Anthropocene extractivism can offer.

Nina Lykke en Risk Hazekamp vonden elkaar in hun liefde voor micro-organismen, meer bepaald Diatomeeën en Cyanobacteriën. Er volgde een warme digitale uitwisseling in woord en beeld, waarin de stemmen van Nina en Risk uiteindelijk samensmolten tot één gedeelde 'ik'. Er ontstond een speculatief en gepassioneerd gesprek waarin ze de precaire omstandigheden van leven en dood op de planeet onderzochten en wegen trachtten te bedenken naar een vreugdevoller en ethischer samenzijn met het planetaire lichaam dan het Antropocene extractivisme kan bieden.

Towards a bio- and geo-egalitarian planetary ethics!

What if every critter’s death was vibrant?1

Ahuman, rhizomatic ecstasy,

vital love-death,

Orpheus’ pain

transformed to music,

and to lushly growing trees.

Coatlicue with her necklace

full of human hearts and skulls,

and her children,

Coyolxauhqui,

Eurydice,

Orpheus,

snakes and ants and stones and peat bogs,

rats and lichen,

slugs and mountains,

cats and humans,

dust and rivers,

ghosts and spirits,

moons and algae,

cosmic black holes,

vira, cancers, and bacteria,

planetary pains and pleasures.

Tricksters everywhere,

dancing to the underworld

crossing thresholds and shapeshifting,

dwelling in a zombie mode

resting, resting, and returning in the spring.

Ancestral critter wisdom

Both Cyanobacteria and Diatoms are micro-organisms invisible to the human eye. Diatoms – a photosynthesizing micro-algae with a unique, coloured silica shell – are single-celled eukaryotes, which means that they have a membrane-covered cell nucleus. They are supposed to have emerged on our planet in the Jurassic epoch around 150 million years ago during the Phanerozoic eon of the Earth’s history. Cyanobacteria are single-celled prokaryotes and as such they do not have a cell nucleus. They are considerably older than Diatoms, dating back to the Archaean eon. Cyanobacteria are considered to have shaped the Great Oxygenation Event 2.3 billion years ago – they were the first life form to obtain energy through photosynthesis – and all aerobic life on earth, including human life, is to be seen as ‘the afterlife of cyanobacteria breath’.2

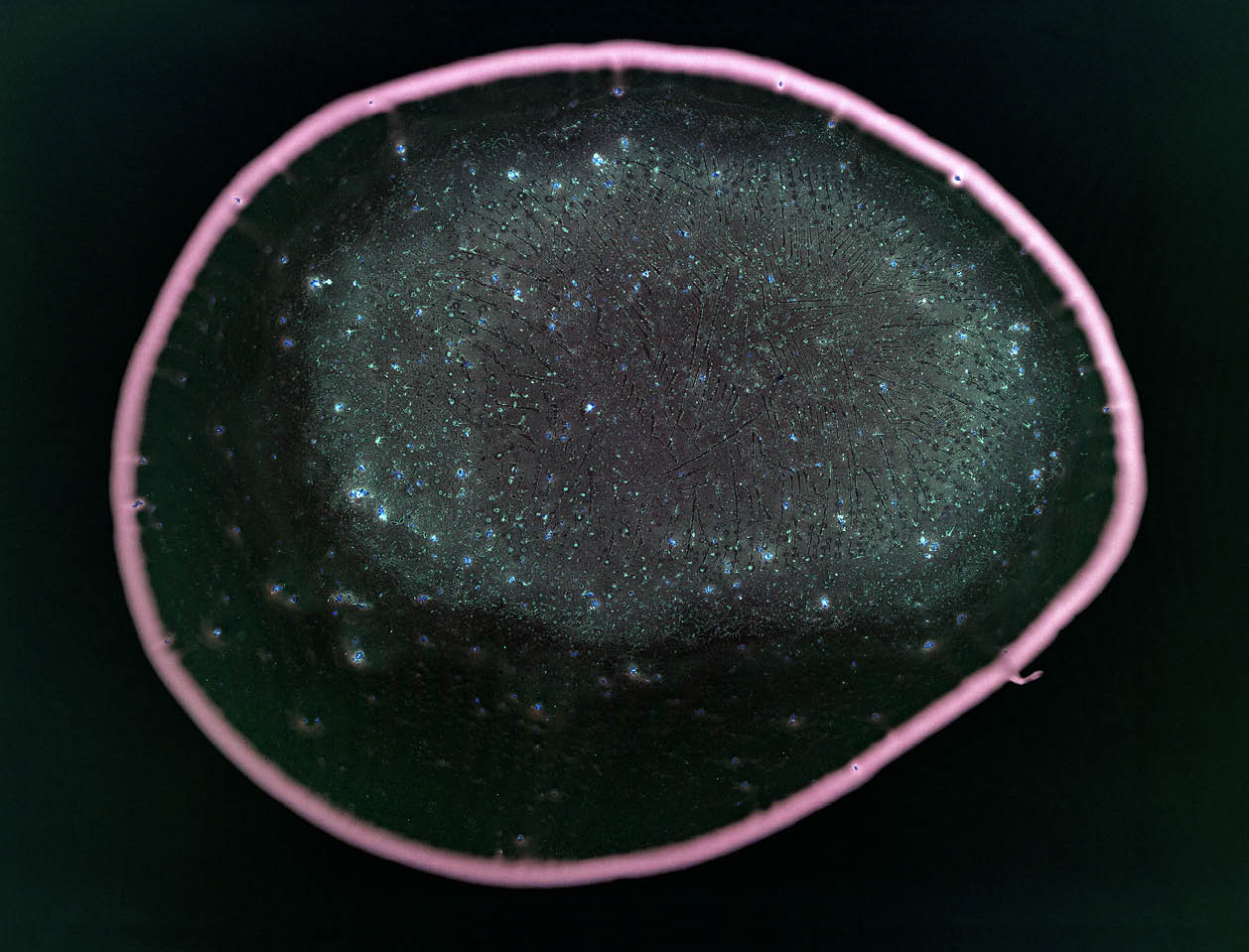

Photograph created by Cyanobacteria interacting with analogue photographic material, such as film negatives, photographic papers or glass film carriers © Risk Hazekamp 2021 or 2022

Dear C.

Photographs created by Cyanobacteria interacting with analogue photographic material, such as film negatives, photographic papers or glass film carriers © Risk Hazekamp 2021 or 2022

The history of biological evolution is most often presented as a linear progression narrative moving from ‘simpler’ to more ‘complex’ organisms.3 Within this narrative, prokaryotes such as Cyanobacteria, which do not have a cell nucleus, are seen as one of the simplest organisms on Earth, even more simple than the eukaryotic Diatoms. But what if, as an artistic gesture, I try to challenge this story of progress? What if I reinterpret the cell nucleus, developed millions of years ago by eukaryotes such as Diatoms, not as a progressive move towards complexity, but as a step in a process that over time gave rise to the sovereign subject, who in today’s Anthropocene world causes a great amount of problems? This kind of reinterpretation would describe the evolution from Cyanobacteria to the human being as a story of decline rather than – as it is usually done – as a narrative of progress.

Basically, I think that both narratives, the one of decline and that of progress, are problematic – both obey the rules of temporal linearity and exclude other perspectives. However, challenging the imagination of modern humans, I think it is interesting to turn the progress story of evolution upside down, and to consider for a moment whether the sovereign ‘I’, cherished by Western modernity, is really a peak or rather a low point in the history of evolution.

Dear D.

Continuing with this line of thought, I would even argue that because of the absence of a nucleus, Cyanobacteria have a special kind of ancestral wisdom floating around inside them – a wisdom that could provide a different perspective and that does not conform to linear rules. This thought reminds me of what happened last summer. I placed some samples of Cyanobacteria that lived in my studio in petri dishes to let them grow new cultures. These petri dishes I took with me to the Ardennes. In the cabin where I stayed, I placed them on the windowsill, but since it was in the forest and the summer was very cloudy, there was not that much light coming in. Yet, against all odds, the cultures grew very well.

After six weeks in the forest, I took the new Cyanobacterial cultures back to my studio and placed them next to the Cyanobacteria from which I had taken the samples. A Cyanobacterial cell can divide at least twenty times in six weeks, which meant that the Cyanobacteria I brought back were now some twenty generations further. Back in my studio, at their place of origin so to say, they settled nearby their ‘ancestors’, which were also flourishing. Within days, however, the Cyanobacteria that had travelled with me faded away and finally became invisible. Did they disappear or change colour? Did they die?

These new Cyanobacterial cultures, that evolved under darker circumstances, could obviously not cope with the light conditions in which their ‘ancestors’ thrived. Apparently, their cellular evolution made it impossible for them to handle so much light. It felt like I had failed them, like I had acted violently towards them in not knowing how to take care of them. This, of course, is a highly anthropocentric and ridiculous thought. In retrospect, I understand that my perception of time in relation to care was far too interventionist, as if only acting and living is caring; caring is also not acting and dying.

Dear C.

Photographs of the diatomite cliffs, beach and seabed at the island of Fur in Limfjorden, Denmark © Nina Lykke 2019

I also came to care immensely about these micro-organisms to whom we owe our lives. Through their photosynthetic processes, Diatoms, my intimate companions, are reported to generate about 20-30% of the planet’s oxygen annually.4 They also contribute to the annual storage in the oceans of at least 20% of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.5 Even though Diatoms emerged much later in the geo- and bio-history of the planet than Cyanobacteria, they are still immensely old compared to humans, and like Cyanobacteria, Diatoms are also central to the Earth’s ecosystems. My intense, queerfeminine desires to co-become with Diatoms emerged after my late, queermasculine, lesbian life partner’s ashes were scattered in the sea off the island of Fur in the Danish fjord, Limfjorden. The seabed and cliffs there are made of 60-metre thick layers of Diatomite, sediments of Diatoms that fossilized 55 million years ago when a subtropical sea covered the area. In the Ice Age, 10,000 years ago, these sediments were in some places pushed up by the ice to form 60-metre-high cliffs. My efforts to co-become with the Diatoms is part of the spiritual-material mourning practices that I have developed after my beloved’s death. I have extended my symphysizing (bodily empathizing) relationship with my partner to the assemblages of waters, fossilized as well as presently living Diatoms, cliffs, seabed… with which her⋆ ashes have merged. The Diatoms have become the centre of my attention because of their impressive posthumous work to build cliffs and seabed.6

I became amazed and enchanted when I got to know about the ways in which the cliffs and seabed at Fur are the result of the phenomenal agency of vibrantly acting Diatom corpses. How onto-epistemologically dizzy but delighted this insight into the agency of dead Diatoms made me feel! The agency of these vibrantly acting 55 million years old Diatom corpses blurred the boundaries between life and death. Backed up by my posthumously acting Diatom companions, I could much more confidently follow my deep desires to leave behind conventional life/death ontologies which opposes the two, casting life as agential and desirable, and death as a gloomy return to the inertia of dull matter, governed by mechanistic laws. The Diatomaceous seabed and cliffs at Fur taught me quite a different story – about the agential vibrancies of all matter, whether alive or dead. Against this background, the Diatoms made me understand that our relationships with the dead are not just confined to a past which is no longer accessible other than through memories of the subject that was; they can unfold within the frame of an ongoing mutuality and embodied relationality, because dead matter is as agential as living matter. Dead or alive, we are all – humans and non-humans – part of the planetary body and as such relationally connected across space, time, and species.

Dear D.

Within this planetary body, I believe that Cyanobacteria possess the knowledge of interdependence, both because they never change, as the divided cell is an exact clone of the original cell, and at the same time they are constantly changing, the process of cell division can be everlasting if the conditions are right. Hence, the knowledge of interdependence that was around billions of years ago can still be here today. A Cyanobacterial cell has eternal life if nutrients and habitat are supplied without restriction. Although these optimal conditions are probably never realised, it is possible for a cell to remain unaltered for millions of years. Although eternal life doesn’t interest me in itself, in relation to the transmission of ancestral knowledge, it intrigues me profoundly. I find comfort in how Cyanobacteria know how to be on and with this planet, how they live in collective ways, how they are always in motion, in a dynamic movement of staying the same and becoming the other through constant cell division.

To look at the single cells and to observe Cyanobacterial cell division I must use a microscope. To be honest, it does feel like voyeurism, peaking into something that is not yours. It makes me wonder about the collectiveness of Cyanobacteria and about their ability to have a regulatory mechanism like quorum sensing: Cyanobacteria and other micro-organisms sense when they are alone, in a small group or when they are in a community. Signal molecules are used to know if they are in abundance and when they sense that they are, they can all act together, they can turn on their collective behaviour. This type of complex communication is called quorum sensing, I consider it a clear example of a form of ancient knowledge, which could contribute to help us learn about precarious survival and joyful co-becoming with our shared planet.

Cyanobacteria, and for that matter Diatoms too, must be in contact in this way all over the planet, so yes, I’m convinced that all micro-organisms possess planetary consciousness – or perhaps better to say that they are planetary consciousness.

Dialogue/Epilogue

Photographs of spontaneous encounters with Cyanobacteria © Risk Hazekamp 2022

Reader: Why do you write this text as an ‘I’, shared between two human interlocutors, Nina and Risk? I am curious to know more about your reasons for departing from the more conventional ‘we’.

Shared ‘I’: The text evolved from an email conversation, sparked by shared interests in queer, more-than-human ancestralities and kinships – Nina’s feelings of compassionate companionship with Diatoms, and Risk’s infinite fascination with Cyanobacteria. We wrote to each other about our loving, curious and respectful relations to these critters, which from anthropocentric vantagepoints are often seen as a nuisance, cast as culprits or accomplices in anthropogenically generated aquatic dead zones. In so doing, each of us used the ‘I’ perspective – and found out that we shared the queer love, (com)passion, and feelings of kinship with these stigmatised critters, which each of us nourished long before we got to know each other. To articulate the feeling of queer sharing that our emails back and forth gave rise to, we edited a shared text in which the ‘I’ is a constant. While perspectives switch, it is not explicitly stated when either Nina or Risk speaks/writes. And although it may appear to be clear who is speaking/writing, the text is a collage of bits and pieces from all our exchanged emails. In this way, the email conversation prompted a move away from a purely subjective personal ‘I’ to a collective ‘I’, without it being a ‘we’, because the exchanged experiences of queer love to micro-organisms are founded in events happening before we met. We found another ‘I’ that expands the ‘me’ as a harmonic sound of micro-organismic and human relationality.

Reader: I am also curious to know more about the artistic statement you make, when you reclaim Diatoms and Cyanobacteria as ancestors and kin, and in so doing turn the progression narrative of evolution upside down.

Shared ‘I’: The claiming of Diatoms and Cyanobacteria as ancestors stems from deeply personal unique experiences which had major implications for the artwork of both Nina and Risk. For Nina, her⋆ love for Diatoms grew out of spiritual-material mourning practices and desires to become one with the watery assemblages (including the seabed and cliffs built by fossilized Diatoms) with which her⋆ beloved life partner’s ashes are merged. The Diatoms confirmed Nina’s desires to understand life and death as a continuum rather than as an opposition, and her⋆ poetry-philosophy became a way of further investigating the possibilities for co-becoming with dead as well as living Diatoms, and for unfolding of an ethics of planetary, more-than-human companionship. For Risk their love for Cyanobacteria stemmed from a deep longing to centre their artistic practice around uncertainty and precariousness. Confronted with both the toxic and racist implications of their much-loved medium of analogue photography, Risk, both as a human being and as an artist working with the medium of photography, started unlearning their role as ‘a cultural agent of imperialism’.7 To this end, a long-term commitment has been made to investigate the possibility of creating breathing images under the guidance of Cyanobacteria, the first organisms to produce large quantities of oxygen in our communal atmosphere.

Secondly, committing to a shared ‘I’, who speaks/writes to a possible ‘you’, alternately named C. (for Cyanobacteria) and D. (for Diatoms) in the text rather than Nina and Risk, takes these individual statements even further. The shared feeling of deep kinship, co-becoming and queer merging with more-than-human critters and a need for the de-exceptionalization of exclusively human positions is given emphasis as a shared artistic statement.

+++

Nina Lykke

is Professor Emerita of Gender Studies at Linköping University, Sweden, and Adjunct Professor at Aarhus University, Denmark. She⋆ is also a queerfemme-inist philosopher-poet and writer. For many years, she⋆ took part in the building of Feminist Studies in Scandinavia and Europe more broadly. She⋆ has recently co-founded international networks for Queer Death Studies and Ecocritical and Decolonial Research. She⋆ has published numerous books and articles, most recently the philosophic-poetic monograph Vibrant Death. A Posthuman Phenomenology of Mourning, Bloomsbury, London 2022.

Risk Hazekamp

is a Dutch interdependent visual artist, researcher, art educator, and a trans-person. Hazekamp completed the Advanced Master of Research in Art & Design at St. Lucas School of Arts Antwerp in 2020 and attended the 2020 and 2021 edition of the María Lugones Decolonial Summer School. They are now a researcher at the Biobased Research Group of CARADT (Avans University, the Netherlands), and they teach in the Art & Research department and the minor Arts & Humanity at St. Joost School of Art & Design in Breda and Den Bosch, the Netherlands.

Noten

- Stanza from Lykke, Nina: “What If Every Critter’s Death Was Vibrant?”. In: Lykke, Nina. Vibrant Death. A Posthuman Phenomenology of Mourning. London: Bloomsbury, 2022, pp. 250-251. www.bloomsbury.com/us/vibrant-death-9781350149731. ↩

- Povinelli, Elizabeth. “Fires, Fogs, Winds”, Elements for a World: FIRE, published in conjunction with the exhibition Let’s Talk about the Weather: Art and Ecology in a Time of Crisis, Sursock Museum, 2016, pp. 21-29. ↩

- Schrader, Astrid. “The Time of Slime: Anthropocentrism in Harmful Algal Reserch”, Environmental Philosophy, 9 (1), 2012, pp. 71-94, and Lykke, Nina. “Co-Becoming with Algae. Between Posthuman Mourning and Wonder in Algae Research”, Catalyst. Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 5 (2), 2019. ↩

- Spaulding, Sarah A., Potapova, Marina G., Bishop, Ian W., Lee, Sylvia S., Gasperak, Tim S., Jovanoska, Elena, Furey, Paula C., Edlund, Mark B. “Diatoms.org: Supporting Taxonomists, Connecting Communities”, Diatom Research, 36 (4), 2021, pp. 291-304, and diatoms.org/what-are-diatoms, last consulted 5 June 2022. ↩

- Scarsini, Matteo, Marchand, Justine, Manoylov, Kalina M., Schoefs, Benoît. “Photosynthesis in Diatoms” In Seckbach, Joseph, and Gordon, Richard. Eds. Diatoms: Fundamentals and Applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2019, pp. 191-211. ↩

- Lykke, 2022. ↩

- Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. “Unlearning Imperial Rights to Take (Photographs)”, Verso Books Blog, 10 October 2018, www.versobooks.com/blogs/4075-unlearning-imperial-rights-to-take-photographs, last consulted 16 June 2022. ↩