Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 32 nr. 1, pp. 48-59

Tekeningen van het huis waar ik woon. De politiek van beeldtaal in architecturale representaties

Nathan De Feyter, Thomas Vanoutrive, Johan De Walsche

This paper investigates the political dimensions of visual language in architectural representation through Participatory Action Research (PAR). It critiques traditional architectural visuals, which often exclude non-expert stakeholders, leading to decisions driven by superficial appeal. The study advocates for alternative forms of representation, including subjective mapping, to enhance communication and inclusivity in design processes. Focusing on Antwerp's “Ten Eekhove” neighbourhood, the research challenges traditional representations, emphasizing accessible visual languages that empower marginalized communities and promote equitable urban development.

Dit artikel onderzoekt de politieke aspecten van architectonische visuele taal via participatief actie-onderzoek. Traditionele architectonische beeldvorming sluit vaak niet-experten uit, wat leidt tot onverwachte uitkomsten die gebaseerd zijn op oppervlakkige esthetiek. De studie pleit voor alternatieve representaties, zoals subjectieve kaarten, om communicatie en inclusiviteit in het ontwerpproces te verbeteren. Met een focus op de Antwerpse wijk 'Ten Eekhove' daagt het onderzoek traditionele weergaven uit en benadrukt het toegankelijke visuele talen die onderdrukte gemeenschappen versterken en een eerlijke stedelijke ontwikkeling bevorderen.

Architecture is a profession that relies heavily on visual communication. In architectural drawing, space is often documented through orthographic projections like plans, sections, and elevations. Besides technical drawings, the visual language of architecture makes use of a wide array of representations including renderings, collages, and photos, each with their specificities and limitations.

Numerous studies have criticized the conventional visualization techniques used by architects.1 One of the main criticisms is that these methods often exclude outsiders. Technical drawings, for instance, are often considered too complex for the average untrained observer. Moreover, architectural representations are known to create perceptions, interpretations, and value judgements that can be different from those produced by actual encounters with the represented environments.2 This might affect decision-making, where better designs are rejected at the expense of projects that are promoted using attractive images. As a consequence, both planners and the public might be left with unexpected outcomes.

Alternative visualization methods can empower individuals and represent them more inclusively in superdiverse day-to-day realities.

This article critiques traditional architectural visualization techniques and advocates for more inclusive and participatory methods. It highlights the limitations of conventional architectural drawings in accurately representing the lived experiences and spatial practices of residents, particularly in superdiverse neighbourhoods.

The following research question guided the research process: How might ‘critical architectural representations’ provide a better insight into the spatial practices of a superdiverse neighbourhood, and how could a better understanding of the diversity of spatial practices change our way of conceiving them?

Through a case study in Antwerp, the research employs Participatory Action Research (PAR) to engage residents in creating visual representations of their homes. The findings underscore the importance of taking the time to listen in order to create inclusive design processes that challenge traditional representations and promote diverse perspectives in urban landscapes. This article concludes by suggesting that participatory methodologies can enhance our understanding of architecture and its impact on communities, encouraging further exploration of these methods as practical tools for cocreating urban environments that reflect the needs and aspirations of their inhabitants.

Visual counter-representation in architecture

In 2013, Nada Bates-Brkljac, an architect and academic, highlighted the need for clearer guidelines on using architectural representations in design decision-making.3 Her findings suggest that using various forms of architectural representations can enhance communication among parties involved in the process. Other experts believe that improving the public's knowledge and communication about architecture can enhance the quality of the built environment.4 To improve the decision-making process among architects, professionals, and laypeople, it is suggested to use client-focused representations that are easy to understand and avoid the use of architectural jargon. This will promote equality and effectiveness in the interaction between these parties.5

More generally, the expert view has also been criticized for its effects. Official housing standards used in slum clearance policies in the 1950s, for example, reflected the value pattern of middle-class professionals. The language used was evaluative, with the goal of replacing existing dwellings with modern housing. In the words of sociologist Herbert J. Gans:

Planners like to describe such housing as ‘obsolescent’. However, it is obsolescent only in relation to their own middle-class standards and, more importantly, their incomes. The term is never used when alley dwellings of technologically similar vintage are rehabilitated for high rentals.6

Critical studies of architectural representations are not limited to deconstructions and critical evaluations, since there are many examples of “counter-representation”. By intentionally deviating from traditional modes of representation in architectural drawing, authors aim to defy norms, question power relations, and offer a critique of culture, society, and politics through alternative architectural visual languages.7 Counter-representations originate from the goal of visualizing a multilayered space that unveils the various layers of architectural ideas, revealing “the real and imagined, introverted and exposed, ephemeral and permanent, precise and poetic, through lines, points, colours, surfaces, lenses and sentences.”8 In this way, architectural drawings can serve as a platform for expressing political or social views and represent marginalized voices. Various representation techniques, such as abstract representations, collages, surreal or dystopian imagery, comic book style, augmented or virtual reality, or political or social commentary, are mobilized for this purpose.9

The findings underscore the significance of inclusive design processes in challenging traditional representations and promoting diverse perspectives within urban landscapes.

In particular, counter-representation initiatives with a focus on participation pay specific attention to how individuals, families, and communities wish to represent themselves, providing them with more recognition and showcasing the variety of existing domestic forms, practices, and rationalities. Such participatory counter-representations may create alternative subjectivities, contribute to the spread of local knowledge, and demonstrate the existence of alternative practices. The creative energies of participants are then central in invented processes, which stand in contrast to the invited forms of participation where the audience has a predetermined role, and carefully choreographed participation events with limited degrees of freedom for participants.10 Societal change is thereby linked to the micropolitics of self-transformation of individuals and the places where they live, since alternative representations may foster the construction of a new identity.11 In particular, marginalized groups that suffer from social stigma and lower self-esteem can benefit from initiatives that construct new identities in which positive agency is attributed to them.

Counter-representations not only play a role in the construction of an improved self-image but also in recognition by others. According to Nishat Awan, an academic, researcher and architect known for her work at the intersection of architecture, migration, and spatial justice, the choices made by architects in terms of what they observe, notice, draw, analyse and thus ‘recognize’ are just as important as the final design proposals they put forward.12 Consequently, she advocates for a different approach to mapping, prioritizing relationships over isolated objects, subjectivity over fixed identities, and temporary politics over ideology. This approach questions a narrow focus on distributive justice and imagines alternative urbanisms that respond to the need for an architecture that is centred on recognizing differences and the empowerment of others.

An example of how architectural drawings contributed to the empowerment and recognition of communities that normally do not engage in the debate around urban renewal can be found in the occupations of downtown São Paulo.13 A latent form of “urbanism in the making” was documented and exposed using maps, diagrams, plans, sections, isometric drawings, taxonomic schemes, infographics, and design images. The creation of these materials illuminated the otherwise hidden realm of occupations, serving as crucial evidence that buildings were systematically occupied over an extended period. Photography and cartography were extensively used as tools for negotiation and as methodological devices to make invisible worlds visible and explain the findings. The exposure was informative not only to the research community or decision-makers but also to the participants and movements themselves. They were able to see the impact and scale of their everyday work for the first time. Their daily management of occupied buildings generated more information and inspiration for others than they were aware of. In other words, the researcher took up

One obvious role for a radical intellectual (…): to look at those who are creating viable alternatives, try to figure out what might be the larger implications of what they are (already) doing, and then offer those ideas back, not as prescriptions, but as contributions, possibilities—as gifts.14

In summary, counter-representation in architecture brings to light and gives voice to stories and perspectives that have been overlooked or silenced. This collaborative approach can reveal hidden layers of meaning and significance in a building or space, helping to create more inclusive and culturally sensitive architectural designs. In this way, the objective is to make the technical human, the invisible visible, the unseen seen, and the dead alive.

Participatory Action Research and the politics of visual language

Besides the examples of and reflections on counter-representations in architecture outlined above, the research presented here was inspired by work on Participatory Action Research (PAR). A key characteristic of PAR is that it aims for social change by collaborating with marginalized communities while focusing on their real needs. This approach rejects hierarchical and extractive forms of knowledge production by a distinct group of expert researchers and sets up collaborative research processes with community members instead of doing research on them.15

This research encourages further exploration of participatory methodologies as practical tools for cocreating urban environments that reflect the needs and dreams of the people who inhabit them.

Based on their experience with PAR and notwithstanding the context-specific nature of such research, Gibson-Graham, the shared pen name of feminist economic geographers Julie Graham and Katherine Gibson, discern three intertwined forms of politics.16 The first one is “language politics”, which is the focus of the current contribution. They assert that fundamental social change is not possible without rejecting, transforming, and reworking dominant framings and discourses that are imposed on—and often internalized by—individuals and communities. For example, during the housing crisis of 2008 to 2014, a social housing movement in Spain challenged the dominant neoliberal model of "personal responsibilization" by using language as a political tool. Slogans like "It is not a crisis, it is a fraud" were used to support those affected by rising rents. By changing and adapting their language, people began to understand that alternative housing models were possible and that the inability to own a house was not a personal failure, but rather a result of structural factors.17

Second, the "politics of the subject" points to the self-transformation of subjects who are empowered and acquire skills during the process. This points to the structural link between research and learning in PAR. For example, in the Protohome Project, a group of individuals facing precarious housing conditions learned building techniques that improved both their self-esteem and skill levels.18 At the same time, the researchers involved in PAR reflect on their personal transformation and see this as part of a collaborative process while avoiding traditional pedagogical ways of monodirectional knowledge transfer.

Third, there is the “politics of collective action”. Although many PAR processes focus on a particular area or neighbourhood, the ultimate aim of PAR is to contribute to social transformation. For example, the goal of small-scale experiments related to housing is to contribute to structural solutions that address housing needs.

This paper focuses on the politics of language in relation to the visual language used by architects. It aims to demonstrate how alternative visualization methods can empower individuals and represent them more inclusively in superdiverse day-to-day realities.

Introducing the case

As outlined above, our research approach called for a case study area where visual architectural representations could be drawn up together with residents. After careful consideration, the “Ten Eekhovelei” in Deurne (Antwerp, Belgium) was chosen. The street is located in one of Antwerp’s most diverse neighbourhoods.19 The media announced in 2019 that Antwerp joined the list of majority-minority cities where people with a migrant background have become the majority of the population.20 The city is thus an example of an urban area that has moved towards a state of superdiversity.21

Nathan De Feyter, Uniform row residences in the Ten Eekhovelei, 2022, photograph. Photo by Nathan De Feyter.

The Ten Eekhovelei is located in a neighbourhood built in the 1930s in northeast Antwerp and is known for its uniform row residences (see image to the right), high population density, and wide-ranging cultural background. Currently, the neighbourhood is mainly featured for its upcoming transition. The Flemish government and the city council plan to create a large park on top of the busy Antwerp ring road, right behind the rowhouses, and the city also plans to firmly upgrade the Ten Eekhovelei and its surroundings in the future, creating ‘momentum’ and interest from both residents and planners, since the future of today’s residents is very much up for discussion.22

Preparatory work has begun, and to minimize inconvenience for residents of Ten Eekhovelei, the city of Antwerp is offering homeowners the option to voluntarily sell their properties.23 The city's offer was valid until 2024 but could be extended. So far (February 2025), 71 homes have been sold, representing about 40 percent of the entire strip. Concerns have been raised about the proposed park, as it involves demolishing existing buildings and constructing new ones, which may result in further displacement of residents from the area. As a result, the case study area may become an example of green gentrification.24

It became clear that there are two distinct groups of individuals who have not yet relocated: those who lack the necessary resources and currently live in precarious or unstable conditions, and those who possess an emotional connection to their current residences and remain steadfast in their desire to remain in the neighbourhood. We observed that both homeowners and renters, each comprising about half of the population on the street, can belong to either group. However, it's important to note that renters are the most vulnerable, since they risk losing their homes if the property owner decides to sell.

Methodology

Given the participatory and creative nature of PAR processes, diverse methods are applied. In general, PAR shows similarities with ethnographic approaches in that it aims to get familiar with the daily lives and practices of members of a community. Ethnographic approaches that combine participatory and knowledge-based planning help to gain a more comprehensive understanding of city inhabitants' daily lives.25 This can include groups that are not usually involved in the planning process, resulting in more cohesive and sustainable urban development. As argued before, current urban planning often lacks inclusivity. It is shaped by a small part of society and relies on fixed ideas about what makes a city attractive.26 Hence, passive observation and generic information meetings have faced criticism; instead, a focus on in-depth case studies and active community engagement is encouraged.27 This can be achieved by taking action in the form of listening, learning, imagining, and collaborating with others to promote both social and spatial justice.28

The research began in early 2022 and included fieldwork such as site visits, photography, sketching, walking, and engaging in informal conversations, mainly by Nathan De Feyter. This fieldwork also involved designing and making plans, diagrams, and schemes from the beginning. In line with the atlases of Subjective Editions, this research ought to encourage dialogue about the spatial practices of our superdiverse day-to-day realities and openly question the dominant ways of representing territories, opening up political scopes, and contributing to a more pluralistic and sensitive territorial identification.29 For the case under study, the method of “subjective mapping” was considered appropriate, since it connects actors, networks, interviews, drawings, photographs, models, stories, and other things based on their spatial association, which provides a valuable layer of knowledge that reveals underlying patterns of behaviour.

The inclusion of nonacademic organizations is also a key feature in PAR, since these have developed longstanding relationships with the neighbourhood, are often action-oriented, and have gained trust among residents. The street features a community centre, which is managed by the NGO SAAMO, an organization familiar with PAR approaches.30 In collaboration with SAAMO, two workshops were organized in the polyvalent space of the community centre during which residents were invited to build scale models of their homes and start conversations about their living conditions. These interactions allowed us to get to know the residents and build trust, ultimately leading to approximately ten home visits. During these visits, we gained insights into the concerns of the community, which included their unrest about future infrastructural works, doubts about whether to sell or leave their homes, and worries about the rising number of vacant, deteriorating houses. During our time spent in various homes, we had the opportunity to engage in conversations about preferred spots, home modifications, their connection with neighbours, and how individuals utilize and personalize their living spaces.

Given the vulnerable situation of many residents and the fact that they gave insight into their homes and ways of living, ethical clearance from the University of Antwerp’s Ethics Committee for Social Sciences and Humanities was obtained prior to this phase. As could be expected, during the first phases of the inquiry, many people had difficulty opening up about their housing situation. This was largely because their day-to-day living conditions were often challenging to put into words. Some participants perceived their living conditions as substandard or unexceptional, while others did not give much importance to their living environment. Relatedly, other pressing concerns such as health issues, debts, and conflicts with landlords or relatives often hindered them from giving serious thought to their living environment.

Effectively conveying spatial practices can prove challenging, particularly through photographs or verbal means. To overcome this obstacle, we discovered that utilizing drawings is a beneficial solution. As an architect, De Feyter naturally relied on architectural drawings to record observations, but this generated a visual language barrier. Conventional drawings such as plan, section, and axonometry drawings were often unclear and failed to capture the emotional experiences of the inhabitants. Participants whose home was drawn in this way had difficulties relating to the documents. Such communication difficulties had previously been identified as one of the major challenges in participatory design, which are caused by differences in knowledge, value systems, and opposing tastes among architects and residents.31 The presentation and rejection of drawings led to interesting interactions between De Feyter and several residents, in which rather technical architectural drawings were gradually transformed into representations that better matched the lived experiences of the participants. The next section describes such interactions, which form the basis of a reflection on housing practices and urban planning.

During the interactions with residents and community centre staff, the researchers reflected on the meaning and value of the research for the community. Several drawings found a place as decoration in the interior of the community centre or the homes of the participants. The idea grew to draw up, apart from drawings of individual homes, a kind of atlas of the neighbourhood. This document is an attempt to record and recognize the lives of those residing in the neighbourhood, which is under threat by the plans to replace existing houses with new residential middle-class housing. This resembles calls to focus on the experiences of disadvantaged groups when involving the community in urban renewal projects, since this can reveal the various obstacles and power dynamics present in public space.32

Results: The drawing as a boundary object and interactional medium

Through the incorporation of the residents' self-made drawings and the integration of new insights that arose after discussing the drawings with them, we had the opportunity to explore alternative forms of visual architectural language, such as models and emotive drawings. By engaging in a collaborative process, we developed a series of communicable drawings, which offered a deeper mutual understanding of the residents' way of life within the house. This allowed us to shift our focus from the house as a mere structure to viewing it as a biography, with greater depth and significance.

In what follows below, we will describe four cocreative trajectories with people living in the Ten Eekhovelei. When we say the drawings are cocreated, it means multiple contributors were involved in shaping and influencing the outcome. However, De Feyter was the one physically holding the pencil in the presented final drawings. Through this collaborative process, each individual played a vital role in refining the drawings, resulting in a shared experience.

From structure to interior and topology

The first set of drawings was made together with a woman from Sub-Saharan Africa who volunteers at the community centre. She lives with her husband in the Ten Eekhovelei. Although her children have moved out, they frequently visit their parents. Also, her grandchildren often stay at the house, making it a warm and welcoming family home.

We had scheduled a meeting to visit her house and discuss the recent renovations that had been made. In preparation for the visit, we created a simple black-and-white section of the house (see image below). We could do that before entering the house because the section was a standard representation for all houses in that area of the street. During the visit, the homeowner showed us the changes they had made, including the demolition of the transverse staircase on the ground floor, which was moved to a rear extension of the house to create a more spacious living area that could accommodate a larger dining table. The kitchen was moved to the extension. However, upstairs, the house had remained mostly in its original state.

Nathan De Feyter, Evolution of the section of a house, in the process of creating a communicating drawing, 2023, drawing. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

Nathan De Feyter, Picture of the residents’ own drawing, 2023, photograph. Photo by Nathan De Feyter.

After making modifications to the first section, we went back to review the drawing. However, it still did not meet the resident’s expectations. The projection of a section did not match her spatial perception. As we reviewed the drawings room by room, we received similar feedback. For instance, she pointed out that her basement was cluttered and in urgent need of cleaning, but this was not visible in the drawing. Additionally, we failed to include her colourful interior with precious wood furniture; and the garden, which was seen as an important extension of the house, was not elaborated enough.

In searching for an accurate representation of the house, we requested the resident to draw her own house (see image to the left). The drawing we received did not follow the standard orthogonal projection. Instead, it included stairs shown in section, doors in elevation, and some rooms in plan, sometimes without walls, and only with the most important elements in that room. Inspired by the representation and spatial connections in the drawing, we reworked our drawing of the house, following the principles of her drawing.

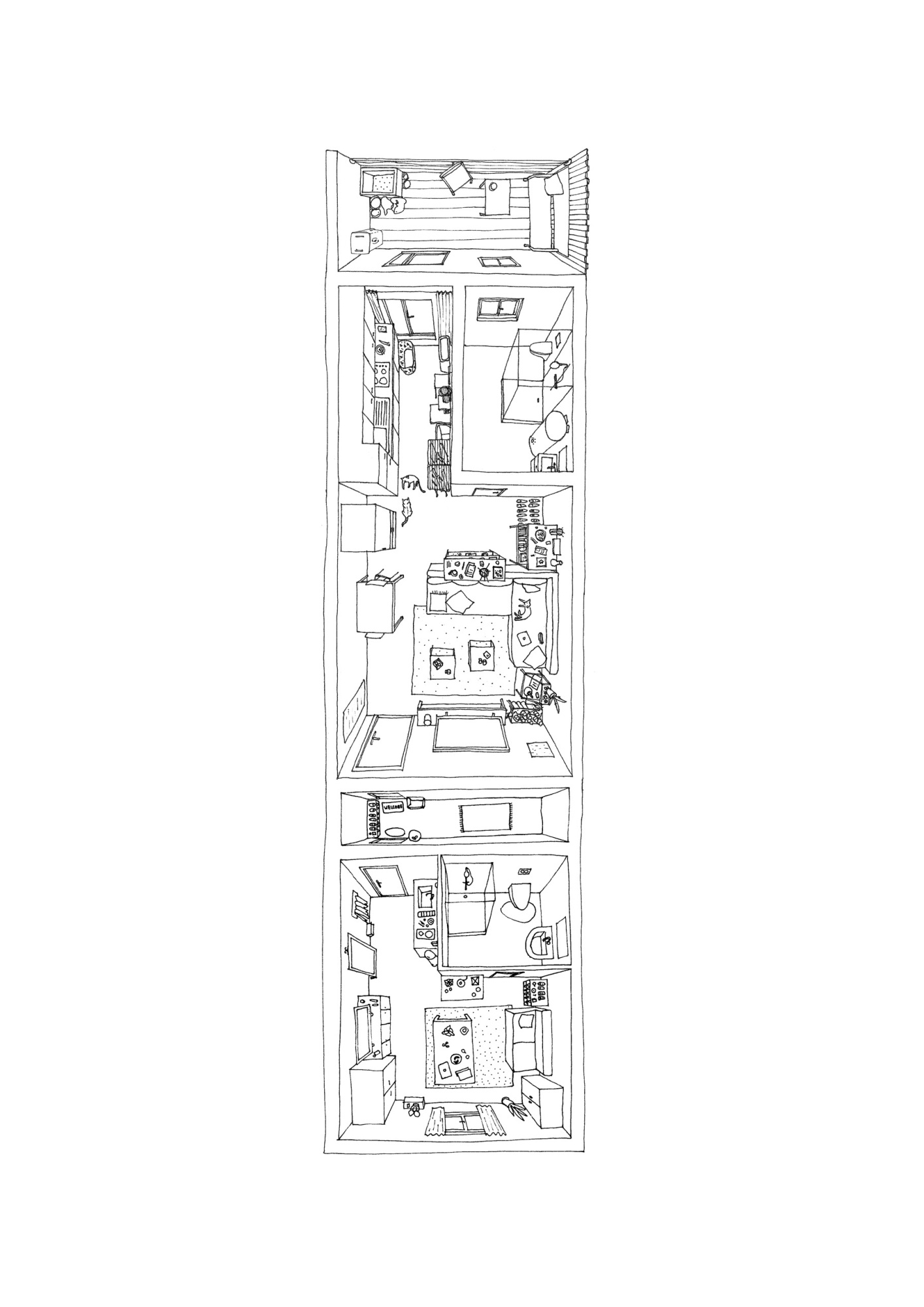

The new version resembles the unfoldment of their house, like a web of interconnected rooms (see image below). It has been carefully drawn with attention to colour, materiality, interior elements, and the spatial sequence of rooms. As a result, it is more relatable and personal for the inhabitants, and it has become an effective tool for communication. It turned out that in the residents’ experience the topological relations between rooms were more important than the physical distance between these spaces. Finally, we gave the printed drawing to the couple, who then hung it up in their home.

Nathan De Feyter, A more relatable and personal representation of the house, 2023, drawing. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

Cultural thresholds: topology and entrance rituals

In late 2023, we visited the home of a family with Turkish roots who moved to Ten Eekhovelei in 2017. The family consists of the parents and their three children, while the grandparents live just a few houses away on the same street. Their home is made up of two combined Conforta houses, with the dividing wall removed. The family occupies both the first and second floors of the double Conforta house. The street level previously served as a local supermarket that appears to have been closed, as the shutters on the street side are always closed. The two occupied floors are divided into two separate units. The first unit consists of a large living space, a kitchen, a bathroom, a playroom, and a bedroom. The second unit has a separate entrance and comprises a second living space, a bathroom, and two bedrooms, where the two oldest children sleep.

Nathan De Feyter, Picture of the residents’ own drawing, 2023, photograph. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

In May 2023, a workshop was held during which the homeowner made a drawing of her own house. The drawing depicts the elevation of the ground floor's facade, showcasing a striking front door (see image to the right). Behind the door is a three-dimensional staircase leading to the first floor. The stairs open into a hallway, with a front door to each unit. One of the doors leads to a corridor that leads to the living room. The drawing only shows furniture in the salon.

During a home visit that took place a few months later, the drawing was used for annotation purposes. When entering the house, the visitor was instructed to follow several steps: taking off shoes at the front door on the street, putting on slippers at the second door to the unit, cleaning hands with rose water when entering the salon, and finally taking a seat on the sofa where coffee and sweets were served. The family takes pride in their Turkish roots, which is evident in the design of the salon, cited as the most beautiful place in the house. All the furniture in the salon was imported from Turkey, as this was considered to have the best quality.

The former retail store on the ground floor, which the residents did not draw, is now rented out to an African church community. They hold a weekly celebration every Sunday morning. We were able to glimpse the renovated and customized space through photos of the property owners and videos posted on Facebook. We did not expect to find such a colourful and vibrant practice behind constantly closed shutters.

The final drawing of the house depicts the residents' experience of the house, highlighting cultural and spatial practices (see the first image below). The front of the house is represented as the public area, while the back is more private and has less colour and detail. The ritual that visitors have to follow is also evident in the topological style of the drawing. The African church, although physically part of the building, was drawn separately, since it is not a part of their home and is used by a different community (see the second image below).

Nathan De Feyter, Drawing highlighting the cultural and spatial practices of the inhabitants, 2023, drawing. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

Nathan De Feyter, Drawing of the African church, 2023, drawing. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

Sharing limited resources

The third set of drawings emerged from a participatory process with a solitary retiree (see below). Since 2002, the man has been renting a one-bedroom apartment on the first floor of a Conforta house. He complained about noise disturbance from the ground floor, which has strained his relationship with the landlord and those who occupy the ground floor.

Nathan De Feyter, Exploded view showing the upstairs neighbours, 2023, drawing. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

Since it became known that the property owners are planning to sell, the man has stopped carrying out maintenance work, such as minor repairs or paintwork. This resulted in a rapid deterioration of the unit, which was already significantly dilapidated. The man is struggling with an outdated kitchen that does not have an exhaust hood. The gas installation in his apartment has been declared unfit for use but no action has been taken yet. The apartment does not have central heating and is solely dependent on a gas heater in the living area. The old boiler is a source of fear for the resident, so he uses the gas heater in the living room to heat water for bathing and washing dishes.

During the home visit, another man was present in the apartment. He was the upstairs neighbour and was also living in a one-bedroom apartment. The neighbour's unit was in an even worse condition. There were malfunctioning light switches, and the kitchen and bathroom were in urgent need of renovation. The bathroom was unheated and uninsulated, which made living conditions even more challenging. Additionally, the neighbour did not have a rental contract or an official residence.

The two neighbours spend a lot of time together, mostly watching TV. During the winter, they sit together in the apartment on the first floor. The warmth from the ground floor unit helps to keep the apartment warm, and this helps to keep their energy costs low. Despite their challenges, their living situation has brought them closer together, allowing them to share experiences and form a strong human connection.

From drawing to action

Nathan De Feyter, Picture of the residents’ own drawing, 2023, photograph. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

Nathan De Feyter, Communal living across units, 2023, drawing. Scan by Nathan De Feyter.

A woman in her late twenties was introduced by an employee at the community centre. She attended one of the workshops at the centre, where she had already created a detailed and well-proportioned ground plan of the existing situation of her home (see the first image to the right), and a meeting to visit her house was scheduled. She lives in one of the five small apartments that were created by dividing a house. Her 25-square-metre unit comprises a living room with a sofa bed, a kitchenette, and a bathroom with a shower and toilet (see the second image to the right). She is single and shares the unit with her three cats. She talked about her desire to create a loft bed in her living space one day because unfolding the sofa for sleeping takes an unnecessary amount of time and effort.

She has become great friends with her neighbour across the hall, and they have set up a semicollective form of living. They share household chores and items. For example, she lets her neighbour use her washing machine in exchange for paying for the detergent for both of them. They watch TV together at the neighbour's house because she has a better TV set. They have also claimed a portion of the hallway for storing their shoes and other items, since their units are too small. This is possible because they live on the top floor, so no one ever passes by. All these actions and spatial practices were not in her original drawing.

When we returned to discuss the drawing after a few weeks, a loft bed had been built in the apartment. She explained this with great enthusiasm, stating that by expressing her housing wishes and thinking about them, she felt empowered to take action and finally solve her main issue with the apartment. In short, speaking about her desires ultimately led to their realization.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the exploration of architectural counter-representation through a participatory method in the context of Ten Eekhovelei, Antwerp, offers valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of community involvement in shaping urban spaces. The collaborative approach not only empowers residents to shape the narrative of their built environment but also fosters a sense of ownership and identity. This conclusion can be framed at different levels: first, by discussing the rich insights into spatial practices, agency, topology, and the effects of architectural drawings, and then reflecting on counter-representation and PAR.

The case shows how mapping and drawing in an interactive way reveals various spatial practices such as sharing a TV, corridor, or washing machine. While traditional architectural drawings emphasize the hard concrete, stone, or wooden structures that form the basic structure of a house, residents put more emphasis on the interior. Presumably, it is no coincidence that participants focused more on those elements that they had added themselves. The furniture and the colour of the walls are the results of their own actions, in contrast to the basic structure of the houses, which has been there since the 1930s. In line with PAR, it was also interesting to see how a conversation with an architect-researcher and the drawing up of a plan inspired one of the respondents to rearrange her apartment.

The mental map of residents seems better represented by topological drawings, which show how one can move from one place to another. This reflects a user perspective, which is less present in more traditional, technical plans. Interestingly, in one of the cases, a path through the house was sketched alongside the acts that visitors are expected to perform. The drawing was thus also a kind of script.

In a context where houses are under threat of being demolished, it can be relevant how the houses are drawn. The drawings are colourful, and life was added by drawing furniture, for example. This generated the reflection that it is easier to demolish a building that is represented as a set of walls, floors, and a roof, than something that is represented as a lively neighbourhood.

The findings underscore the significance of inclusive design processes in challenging traditional representations and promoting diverse perspectives within urban landscapes. The Ten Eekhovelei study is an example of how involving the community can help us better understand space and create more inclusive built environments. It shows how participatory methodologies can enrich our understanding of architecture and therefore its impact on communities. This research encourages further exploration of participatory methodologies as practical tools for cocreating urban environments that reflect the needs and dreams of the people who inhabit them.

This collaborative approach not only empowers marginalized communities but also fosters improved communication among architects, planners, and residents. This leads to better design decisions and promotes more equitable urban development.

The findings are derived from in-depth conversations with residents, highlighting that by actively listening, we can enhance existing representation techniques. As an architect, it is essential to focus on elements that resonate deeply with the residents. There is something almost enchanting about incorporating specific details—like illustrating a sofa in the living room—since it can significantly enhance the clarity of the plan for all parties involved.

Next steps

Building on the insights derived from the cocreated critical drawings and their capacity to reveal profound insights about the case, the next step for this research aims to shift from drawing to design. The participatory and ethnographic approaches used in the initial research phase have provided a deep understanding of the community's spatial practices, concerns, and aspirations. This foundation will inform the participatory design process, ensuring that the voices of residents continue to shape the development of their neighbourhood.

The goal is to shed more light on the emancipatory and transformative impact of a collaborative design process and explore the possible emancipatory potential inherent in cocreated architectural designs within the context of design-driven Participatory Action Research. By maintaining a focus on inclusivity and community involvement, the design phase will perpetuate the unique characteristics of the neighbourhood and address the specific needs and dreams of its residents.

During the design phase, to perpetuate the unique characteristics of the neighbourhood, an iterative process of design workshops and roundtables with residents, people from the community centre, and meetings with the vacancy manager and state agencies will be executed. All meetings will aim to collect feedback on spatial requirements and improve services for residents. During the critical design workshops, several potential uses for vacant properties will be pictured, all focusing on neighbourhood-oriented and future-oriented alternatives to the city's plans.

During a later phase, it is crucial to equip the residents with arguments to actively participate in the implementation process. Capacity-building workshops on relevant skills such as sustainable practices and construction techniques can enhance the community's ability to contribute to the project and achieve critical practice. Additionally, it is necessary to explore funding opportunities and resources that can support the implementation phase. This may involve seeking grants, partnering with local businesses, or collaborating with governmental and nongovernmental organizations.

Critical drawing, design, and practice collaborate to challenge conventional thinking, rethink societal norms, and fuel creative thinking. This triangular relationship promotes reflection and positive change in society, ensuring that the urban development process is equitable, inclusive, and reflective of the community's lived experiences.

+++

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all the residents of Ten Eekhovelei who have contributed to the content of this article in any way. We also extend our gratitude to the staff and volunteers of community centre Dinamo for making the workshops and interviews possible and for the warm hospitality they offer to everyone.

Furthermore, we would like to thank SAAMO Antwerpen, AG Vespa, and the University of Antwerp for their valuable input and feedback. Without your contributions, this article would not have been possible.

Nathan De Feyter

is a teaching and research assistant in architecture at the University of Antwerp’s Faculty of Design Sciences. His research examines the various roles that designer-researchers can adopt within action research, exploring the connections between insights from fieldwork and existing theoretical frameworks.

Thomas Vanoutrive

is an associate professor at the Research Group for Urban Development, University of Antwerp, and is also a member of the Urban Studies Institute. His research focuses on transport justice and mobility-related social exclusion.

Johan De Walsche

is an associate professor in architecture at the University of Antwerp’s Faculty of Design Sciences. His research interests include methodologies of practice-based and architectural design research, with a focus on their transformative and emancipatory potential.

Noten

- See, for example: Bates-Brkljac, Nada. "Towards Client-Focused Architectural Representations as a Facilitator for Improved Design Decision-Making Process." Proceedings of DDSS, 2008, pp. 7–10; Sheppard, Stephen R. J. Visual Simulation: A User's Guide for Architects, Engineers, and Planners. Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1989. ↩

- Daniel, Terry C. and Matthew M. Meitner. "Representational Validity of Landscape Visualizations: The Effects of Graphical Realism on Perceived Scenic Beauty of Forest Vistas." Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 21, no. 1, 2001, pp. 61–72. ↩

- Bates-Brkljac, Nada. "Differences and Similarities in Perceptions of Architectural Representations: Expert and Non-Expert Observers." Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 2013, pp. 91–107. ↩

- Markus, Thomas A. and Deborah Cameron. The Words between the Spaces: Buildings and Language. Psychology Press, 2002. ↩

- Wyatt, Ray. "The Great Divide: Differences in Style between Architects and Urban Planners." Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, vol. 38, 2004, pp. 38–54. ↩

- Gans, Herbert J. "The Human Implications of Current Redevelopment and Relocation Planning." Journal of the American Institute of Planners, vol. 25, no. 1, 1959, pp. 15–26 (p. 16), doi.org/10.1080/01944365908978294. ↩

- Singer, Joshua. Counter-Design: Alternative Design and Research Methods. Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. ↩

- Riahi, Pari. "Expanding the Boundaries of Architectural Representation." The Journal of Architecture, vol. 22, no. 5, 2017, pp. 815–24. ↩

- Vroman, Liselotte and Corneel Cannaerts. "Other Perspectives: Extending the Architectural Representation." Research in Arts and Education, no. 2, 2022, pp. 12–24. ↩

- See, for example: Miraftab, Faranak. "Insurgent Planning: Situating Radical Planning in the Global South." Planning Theory, vol. 8, no. 1, 2009, pp. 32–50. doi.org/10.1177/1473095208099297; MacLeod, Gordon. "New Urbanism/Smart Growth in the Scottish Highlands: Mobile Policies and Post-Politics in Local Development Planning." Urban Studies, vol. 50, no. 11, 2013, pp. 2196–2221. doi.org/10.1177/0042098013491164. ↩

- Di Feliciantonio, Cesare. "Social Movements and Alternative Housing Models: Practicing the 'Politics of Possibilities' in Spain." Housing Theory and Society, vol. 34, 2017, pp. 38–56. ↩

- Awan, Nishat. Diasporic Agencies: Mapping the City Otherwise. Taylor & Francis, 2017. ↩

- See: Stevens, Jeroen. Occupation & City: The Proto-Urbanism of Urban Movements in Central São Paulo. 2018. KU Leuven, PhD dissertation; Stevens, Jeroen. "Prototypes of Urbanism: Urban Movements Occupying Central São Paulo." Geography Research Forum, vol. 38, 2018, pp. 43–65; Stevens, Jeroen. "Occupy, Resist, Construct, Dwell! A Genealogy of Urban Occupation Movements in Central São Paulo." Radical Housing Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, 2019, pp. 131–49. ↩

- Graeber, David. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004 (p.12). ↩

- Pain, Rachel, Matt Finn, Rebecca Bouveng, and Gloria Ngobe. "Productive Tensions—Engaging Geography Students in Participatory Action Research with Communities." Journal of Geography in Higher Education, vol. 37, no. 1, 2013, pp. 28–43. ↩

- See: Gibson-Graham, J. K. "Traversing the Fantasy of Sufficiency: A Response to Aguilar, Kelly, Laurie, and Lawson." Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, vol. 26, no. 2, 2005, pp. 119–126. doi.org/10.1111/j.0129-7619.2005.00208.x; Gibson-Graham, J. K. A Postcapitalist Politics. University of Minnesota Press, 2006. ↩

- Di Feliciantonio. ↩

- Heslop, Julia. "Learning through Building: Participatory Action Research and the Production of Housing." Housing Studies, 2020, pp. 1–29. doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1732880. ↩

- Stad Antwerpen. "Stad in Cijfers - Databank." Stad Antwerpen, 2023. Accessed 20 Feb. 2023, stadincijfers.antwerpen.be/databank. ↩

- VRT NWS. "In Antwerpen zijn er voor het eerst meer inwoners met migratieachtergrond dan zonder." VRT NWS, 25 Feb. 2019, www.vrt.be/vrtnws/nl/2019/02/25. ↩

- Geldof, Dirk. Superdiversity in the Heart of Europe. Acco, 2016. ↩

- Ringpark het Schijn. "De Grote Verbinding." De Grote Verbinding, 2022. Accessed 16 Aug. 2023, www.degroteverbinding.be/nl/projecten/ringpark-schijn/over. ↩

- AG Vespa. "Stad Biedt Deel Eigenaars Ten Eekhovelei Vrijblijvend Aan om Hun Pand te Kopen." AG Vespa, 2021. Accessed 16 Aug. 2023, www.agvespa.be/nieuws/stad-biedt-deel-eigenaars-ten-eekhovelei-vrijblijvend-aan-om-hun-pand-te-kopen. ↩

- See, for example: García-Lamarca, Melissa, Isabelle Anguelovski, Helen V. S. Cole, et al. "Urban Green Grabbing: Residential Real-Estate Developers’ Discourse and Practice in Gentrifying Global North Neighborhoods." Geoforum, vol. 128, 2022, pp. 1–10; Gould, Kenneth A. and Tammy L. Lewis. Green Gentrification: Urban Sustainability and the Struggle for Environmental Justice. Routledge, 2017. ↩

- Mattila, Helena, Pia Olsson, Tiina-Riita Lappi, and Karoliina Ojanen. "Ethnographic Knowledge in Urban Planning – Bridging the Gap between the Theories of Knowledge-Based and Communicative Planning." Planning Theory & Practice, vol. 23, no. 1, 2022, pp. 11–25. ↩

- See, for example: Agyeman, Julian. "Interview Conducted with Gerald Taylor Aiken." Spatial Justice, no. 17, 2022; Ortiz Escalante, Sandra and Blanca Gutiérrez Valdivia. "Planning from Below: Using Feminist Participatory Methods to Increase Women’s Participation in Urban Planning." Gender & Development, vol. 23, no. 1, 2015, pp. 113–26. ↩

- Leveratto, Jacopo, Francesca Gotti, and Francesca Lanz. "The Iceberg, the Stage, and the Kitchen." Diversity of Belonging in Europe, ed. by Sarah Eckersley and Charles Vos, 1st ed., Routledge, 2022, pp. 100–16. ↩

- See, for example: Askins, Kye. "Feminist Geographies and Participatory Action Research: Co-Producing Narratives with People and Place." Gender, Place & Culture, vol. 25, no. 9, 2018, pp. 1277–94; Brinton Lykes, M. and Alison Crosby. "Feminist Practice of Community and Participatory and Action Research." Feminist Research Practice: A Primer, ed. by Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber, SAGE Publications, 2014, pp. 145–81. ↩

- Subjective Editions. "About." Subjective Editions, 2023. Accessed 16 Aug. 2023, www.subjectiveeditions.org/about. ↩

- Hautekeur, Guido. Van Cohousing tot Volkstuin: De Opmars van een Andere Economie. Epo/Samenlevingsopbouw Vlaanderen, 2017. ↩

- Albrecht, Johann. "Towards a Theory of Participation in Architecture: An Examination of Humanistic Planning Theories." Journal of Architectural Education, vol. 42, no. 1, 1988, pp. 24–31. ↩

- Beebeejaun, Yasminah. "Gender, Urban Space, and the Right to Everyday Life." Journal of Urban Affairs, vol. 39, no. 3, 2017, pp. 323–34. ↩