Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 32 nr. 1, pp. 12-21

De esthetische essentie van spel – De “Power of Maddening”. Het model van de speeltoestand – Abstracte dynamische speelvelden

Veronika Szalai

This contribution explores the aesthetic nature of play from the player's perspective, examining the “power of maddening” inherent in play states. It delves into the emotional fabric of play while investigating the traces of responsibility embedded in predesigned structures.

Deze bijdrage onderzoekt de esthetische aard van spel vanuit het perspectief van de speler en analyseert de ‘kracht van gekte’ die inherent is aan speelsituaties. Het verdiept zich in de emotionele structuur van spel en onderzoekt de sporen van verantwoordelijkheid die zijn verweven in vooraf ontworpen structuren.

My Doctor of Liberal Arts (DLA) thesis, The Model of the Play State, explores the essence of play from the player’s1 perspective, uncovering its intrinsic “power of maddening.” In my conceptual framework, the “play state” refers to an abstract field within the player's consciousness, in which their actions unfold.2 The concept of the power of maddening is borrowed from the Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga. In his book Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, Huizinga defines play as a universal pattern of human relationships, collectively shared across cultures, and even preceding their development.3 For instance, he connects human activities such as rituals, warfare, law, science, and the arts to the concept of play.

A composition of the model of play state, 2023, by Veronika Szalai. Puppet artist: Borbála Egri. Photo by Csanád Szesztay.

Huizinga also raises an essential question within the cultural context: the player’s perspective. He asks: What is play itself? What does it mean for the player? What is the aesthetic quality of play? He writes:

What actually is the fun of playing? Why does the baby crow with pleasure? Why does the gambler lose himself in his passion? Why is a huge crowd roused to frenzy by a football match? (…) in this intensity, this absorption, this power of maddening, lies the very essence, the primordial quality of play.4

My research is built upon three pillars: the collective, personal, and aesthetic dimensions of play. Play is conceptualized as a phenomenon that enables an exploration of various human actions that generate a play state in the player.5 The methodology of my research comprises two key steps. The first involves conceptual-logical analysis, in which I have gathered and synthesized the fundamental concepts and underlying components of play, constructing abstract, dynamic conceptual fields of the play state. The second step adopts an experimental and aesthetic approach. Because aesthetic experience cannot be fully encapsulated through conceptual-logical thinking, the physical object I present here serves as a nuanced artistic interpretation of the conceptual framework.

Dynamic conceptual fields of play

Play’s ability to command full attention and reshape spatial perception highlights its unique aesthetic and existential qualities.

When I observe children at play, I am fascinated by the impulsive space they create around themselves and the way they perceive it. This space is not static; it is fluid, ever-changing, and responsive to the children's actions and perceptions. I am particularly interested in understanding what the state of play means to them at that specific moment. Capturing the essence of the “now” is crucial, as children’s expressions reveal that each successive moment redefines the situation. Moment by moment, different impulses take over: the environment changes, and the player changes too. This dynamic process creates a space that is neither fixed nor predetermined. It is a spontaneous and natural activity that overrides the player’s hunger, tiredness, or other physical needs, generating a transformative space that is difficult for the player to leave voluntarily. Play’s ability to command full attention and reshape spatial perception highlights its unique aesthetic and existential qualities.

The meaning of play is not determined solely by the players themselves but also by those who observe, define, and design it. This duality reflects the complex nature of play as both a personal experience and a conceptual construct. The way play is interpreted differs significantly depending on cultural, social, and academic perspectives. Research into the definitions of play highlights these inherent complexities. Diverse approaches from various historical and disciplinary contexts expose contradictions in how play is understood. Despite these differences, I believe it is still possible to articulate the content (“conditions,” “elements,” and “properties”) and structure of the play state in a way that encompasses its subjective essence. This content consists of abstract concepts that are closely interconnected, thus defining the conceptual field of play where the player exists moment to moment.

To address these complexities, my research begins with a comprehensive examination of existing definitions and theoretical frameworks related to play. Drawing on perspectives from a range of disciplines – including sociology, psychology, and game design – I seek to develop a holistic understanding of the play state. By integrating insights from these fields, I aim to bridge the gaps between conceptual analysis and subjective experience.

Analysis of play state in Francis Alÿs's video Step on a Crack

A sprite in a blue pinafore, plimsolls, and white facemask flits through Hong Kong, enclosed in a quicksilver bubble of magic. Streets become the dull, slow backdrop to her vividness. Oblivious to storefronts and curious stares, seeing only the yellow lines and the cracks in the pavement, she snakes and two-steps around seams and lines without loss of élan, chanting spells that shade into vague sounds. “Step on a line, break the devil’s spine, Step on a crack, break the devil’s back, Step in a ditch, your mother’s nose will itch. But if you step in between, everything will be keen!” By igniting her route with meaning, she briefly wrests public space from the commercial values this city lives by.6

In Francis Alÿs’s interdisciplinary artwork Step on a Crack, we see the scene described in the above quote.7 The play-based activity presented here serves as an illustrative example of a situation where the goal is not merely to move from one point to another but to explore a new and unique aspect offered by the physical space itself. The aim of the aesthetic experience is not for the player to approach the intended meaning as quickly as possible, but rather to make the process of approaching meaning an interesting experience in itself.8 Through the analysis of this simple activity, I will present the model of the play state – what it means for the player “to be in a play state” at a given moment. I will also explore the force that, in my view, represents the power of maddening during play. A key part of the analysis involves identifying and distinguishing the properties and elements of the play state. The properties of the play state are those aspects that can be easily represented physically, such as visible and audible features. The properties observed in the video can be described as follows:

- (1) Constraints and freedom: The human body, the street pattern, and the nursery rhyme each serve as factors that both constrain and enable play.

- (2) Physical play space and time: Rhyming movement, graphic rhyme, and rhythm influence the experience of time, the speed of progression, and the experience of pauses and silence.

- (3) Goal and focus: The goal is to synchronize the body’s movement with the graphic rhyme and the rhythm of the nursery rhyme. The player’s focus is concentrated on the moment-to-moment planning and execution of actions.

These properties shape the player's immediate experience but can be further abstracted into elements – deeper foundational structures and aesthetic dimensions of the play state, which are more challenging to represent physically. The elements of the play state delve deeper into the internal dynamics of the play experience. These elements include:

- (1) Emotional engagement: The player’s engagement with the activity arises from the previously established goal, which creates a context that defines what kinds of interactions are positively valued. The challenge lies in synchronizing bodily movement with the rhythm of the nursery rhyme and the graphic signs. Accepting this challenge represents an act of emotional engagement. This engagement legitimizes the abstract nature of the play space and imbues the player’s actions with tension, meaning, and significance.

- (2) Motivation/ Motive/ Tension: In this context, the challenge itself becomes the source of both tension and joy. The premise is simple, as is the central question: Can the player jump in rhythm without stepping on the lines? Tension inherently contains the possibility of failure, while successfully meeting the challenge brings joy. This action can be conceptualized as a straight line, with the sensation of tension at one end and the sensation of joy at the other. As the player navigates the painted lines on the street, this line shifts back and forth between tension and pleasure. However, there may be multiple sources of tension and pleasure in action, such as the tension and pleasure of adaptation, decision-making or strategy, movement, or presence. In play, these emotions form a dynamic system, building upon one another as they pull, attract, or repel each other. This structure is held together by the concepts of presence and intention.

- (3) Presence and intention: Presence and intention, together, provide continuous feedback on the player's actions, organizing the emotions evoked by emotional engagement into one or more “chains of intention”.9 They personalise and operationalise the chains of intention.

In the example I have chosen, I will analyse a chain of intentions that begins with the moment of engagement and concludes with the landing after skipping the painted line. This chain of intentions follows four axes, which represent the starting and ending points of different intentions:

- (A) Emotional engagement: The player emotionally commits to the action, setting the stakes for success or failure.

- (B) P-intention (present-oriented): The player decides how to attempt to overcome the challenge.

- (C) M-intention (motor): The player takes the action.

- (D) D-intention (future-oriented): Successful execution confirms the player's ability to act in the space.

A sequence of the model of play state, 2023, by Veronika Szalai. Photo by Csanád Szesztay.

Each of these elements is associated with specific emotions. For instance, the joy of successful adaptation interacts with the tension of present-oriented intention, which then influences the player’s future-oriented intention. This dynamic follows a cyclical pattern, where success in one element fosters joy that propels the next intention. The experience continues until the chain of intention either closes into a loop (as actions become repetitive), becomes blocked (due to an obstacle), or loses momentum (as the player disengages). This movement – or the transformation of space – persists until one of these outcomes occurs. Each manipulation of the space by the player reveals new and unfamiliar aspects.

This analysis highlights how the dynamic conceptual field of play reshapes everyday space into one imbued with meaning, where the interaction between presence, intention, and emotional engagement fosters a continuously evolving experience. This dynamic conceptual space takes shape as emotional points connect to form a network, revealing how emotions weave into one or more chains of intention and how the player's actions shift this abstract space from one state to another. The space becomes fluid, leaving transient imprints that continue to oscillate between different states. However, this conceptual framework alone does not fully capture the aesthetic essence of the play state. To address this, I first reflect on my personal experience of a play state before demonstrating how I integrate this theoretical framework with subjective experience in my artistic interpretation.

Subjective experience of play state

One of my most profound experiences with play-based activities is cave exploration. Over nearly twenty years, I have accumulated a wealth of vivid, intense, and deeply personal images, sounds, and sensations that I cherish.

On one particularly memorable occasion, after hours of snowshoeing, we arrived at a metal door lying flat on the ground. Carrying all the equipment needed for exploration, along with a week’s provisions on our backs, we prepared ourselves for the journey below. After changing into our caving gear, we crawled through the door and closed it behind us – a sound I can still recall with striking clarity. As a child, I had read about this place, studied its maps with fascination, and dreamt of standing here one day. Now, it was real. There were just five of us, relying solely on what we had brought from the surface.

What followed was half a day of descending shafts and ropes, manoeuvring equipment through narrow passages. At one such passage, the space suddenly widened as we emerged at the top of a vast chamber. We abseiled down and arrived at our first bivouac, a temporary sleeping area, knowing the research point was still two days away. The cave’s character continually shifted. Every few hours, it felt as if we were entering a new realm: rope courses, vertical climbs, horizontal crawls, dry passages, and waterfalls. It was a journey to the centre of the Earth.

Eventually, we reached one of the endpoints of Romania’s deepest caves, more than 600 metres below the surface and several days from the only exit. In a narrow, muddy crevasse, so confined we could barely turn our heads, we inched sideways. Beneath us lay water just two degrees above freezing, while rubble loomed overhead. We could only sense the presence of our companion behind us by the faint scraping of boots seeking footholds on the wall. Fear, pain, dizziness, and hunger took turns occupying our minds, but all were eclipsed by the draught on our faces – an unmistakable sign that a new space awaited.

Emerging from the crevice, we stood in a chamber no one had ever seen before. The draught dissipated, and with it, the sense of self and other. In that moment, we dissolved into the space – a discovery shared by no one else before us.

Some trajectories of the model of play state, 2023, by Veronika Szalai. Puppet artist: Borbála Egri. Video by Csanád Szesztay and Bea Pántya.

When we finally emerged at the surface, still wearing the same torn and mud-caked overalls we had lived in for a week, we felt an inner sense of harmony. The experience had granted us the rare chance to be fully present, to understand the profound responsibility we bore for one another, and to feel the weight of our decisions – all of which are intrinsic to this form of “play”. Here lies the true power of “being in the play” at its most extreme edge, where the dividing line between good and bad decisions becomes perilously thin.

This subjective experience aligns with the concept of play as defined by sociologist and ludologist Roger Caillois, who expanded it to encompass a vast range of pleasurable activities. He classified human behaviour in terms of play into four main categories, based on the emotional substrates these actions evoke. One of these is “ilinx,” or “vertigo,” which includes activities such as parachuting, riding a carousel, or caving. In every play-based activity, each player brings unique elements and properties. Yet, they also share certain universal traits, forming a cohesive whole that defines the quality of the play state.

For me, these experiences exist at one extreme of the imaginary spectrum of “being in the play.” At the opposite end lie play-based activities driven by quantifiable external motivations, such as so-called coupon-collecting campaigns. No measurable achievement can ever match the satisfaction of that singular moment when everyone emerges from the “play.”

General elements, properties and structure of play: The aesthetic essence of play

It is important to recognize that play, as an activity, is typically self-imposed and pursued for its own sake, driven by what social psychologist Barbara Fredrickson and her colleagues describe as an inner “psychological common currency”.10 This currency provides players with positive reinforcement, encouraging them to take risks and repeatedly engage in play-based activities. This power of maddening could be understood as the aesthetic experience of the play state, fundamentally composed of the player's emotions. These emotions appear to form a meaningful feedback loop that drives the continuation of the activity.

During play, the aesthetic experience might be perceived as a network of emotions. This is akin to an orchestra's performance, where the music played by each musician is woven together by the conductor, who signals when each instrument enters and exits. In the examples above, the conductor is the player, as these play-based activities are not deliberately designed but evolve spontaneously.

The structure of emotions is shaped by the fundamental properties of play as a system, generating a spatial experience that is fluid, malleable, and immersive – capable of suppressing hunger, fatigue, and fear. In this process, every action of the player enhances the allure of the play space. This structure is open, adaptable, and flexible, yet solid, allowing for infinite forms and a variety of repeatable, free movements. The general properties of the play state incorporate concepts from the theoretical framework, which can often be arranged in pairs of antonyms: open-closed, constant-changeable, stable-fluctuating, controlled-uncontrollable, random-systematic, sharp-rough, rigid-flexible, rational-irrational, bound-unbound.

When physically represented, these pairs reveal an interdependent relationship in which each concept presupposes its opposite, shaping a space that, I believe, underlies a high-quality play state. This, in turn, may help us develop a deeper and more complex understanding of the nature of play-based activities in the future.

Traces of responsibility in predesigned structures

What happens to this space if it is not constructed by the player but is instead predesigned? To explore this question, I have transformed the dynamic conceptual fields of play state presented above into a physical object. These objects consist of nodes / points (elements) and the connecting segments / line between them (properties), both of which define the malleability of the mesh. I have built several models to explore this issue. My aim was to gain a physical understanding of how structures with different qualities respond when I attempt to move a single point in space, and how this affects the other nodes of the system. How predictable, controllable, or repeatable are these movements? What kind of space emerges as a result – how schematic or organic, how rigid or adaptable, and so on?

All my spatial experiments revolve around the concept of play state, yet the flexibility and quality of these spaces vary. The physical attributes of the materials used in the experiments had a significant influence on the mutability of the space.

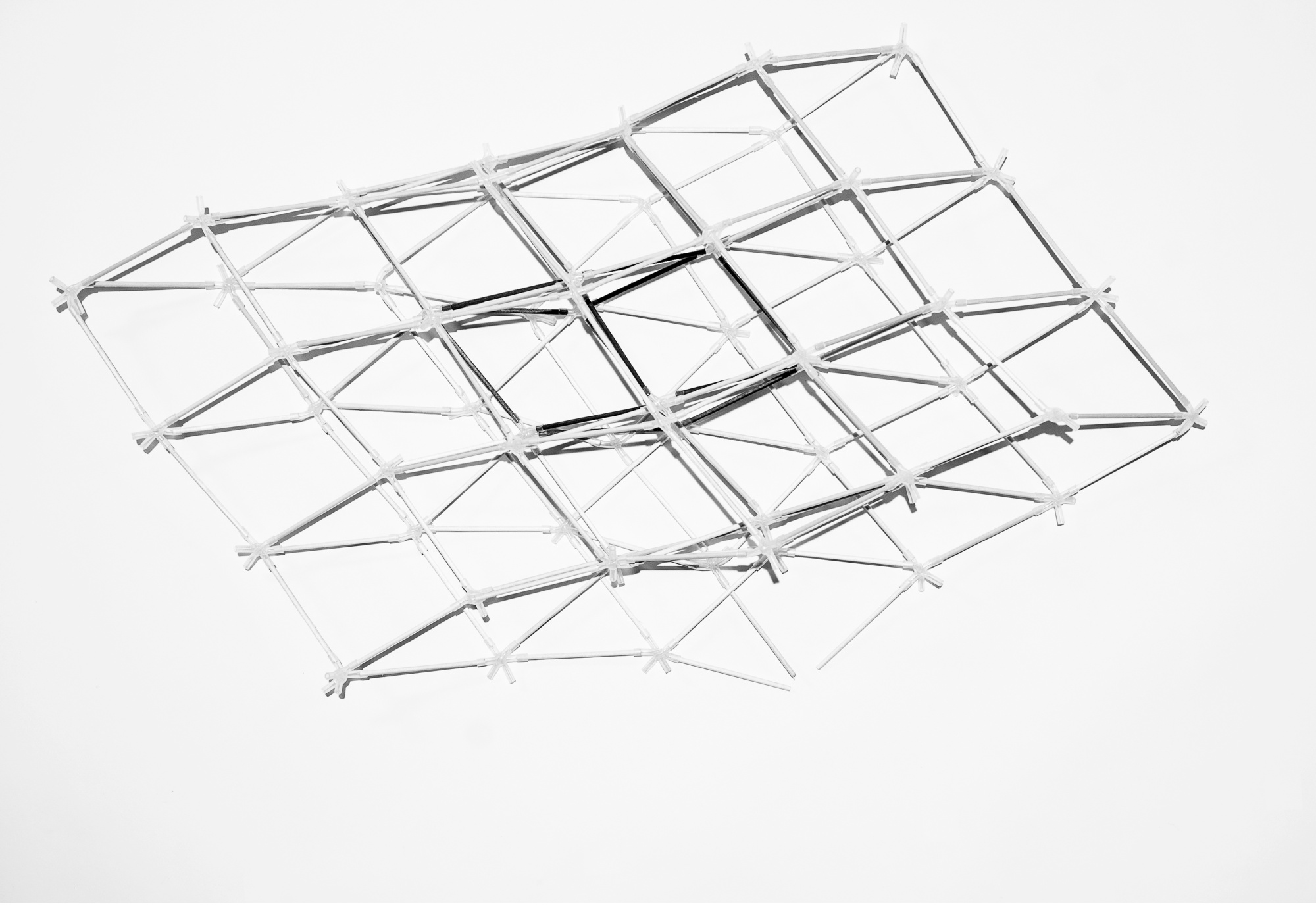

Figure 5, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

To construct the spatial arrangements, I primarily used rubber and metal wire, as well as metal, plastic, and silicone tubes, along with wooden rods. Among these materials, rubber was the most flexible. I used it, for example, to create a spatial structure where its elongation enabled fixing points in such a way that moving one point did not directly influence the movement of others in the system. This setup allowed for an observation of how many directions a point needed to be pulled to keep it fixed, as well as what movement occurred when a point was released and how it transferred momentum to the system. This was the most flexible yet also the most challenging space to manipulate in my experiments (see Figure 5). To prevent this space from collapsing, continuous pulling from all points and directions was necessary. I did not have enough hands and feet to accomplish this alone. There was never a regular, comparable, or repeatable way to stretch or move the space I was manipulating. Despite these difficulties, I enjoyed ‘playing’ with it, as each time I stretched it, I was reminded of the cat's cradle game. In this game, two players manipulate an endless rubber band: one player loops the rubber around their hands, then stretches the space with their fingers and passes it to their partner. The second player grasps the system at the string’s intersection points and, as they take over, reshapes it into a different form. This reciprocal, back-and-forth, free spatial formation was what fascinated me about this game.

Figure 4c, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

A much more rigid structure is one in which the nodes are made of flexible material, but the sections connecting them are rigid. In manipulating this space, I found it intriguing that I did not need all my hands and feet to stretch it alone; instead, grasping two ideal points within the system was sufficient to control it (see Figure 4). This was somewhat similar to controlling marionette puppets – grasping a few well-chosen points allowed the entire system to be moved in a varied and repeatable manner.

Figure 4a, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

Figure 4b, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

I also experimented with configurations where one node was rigid – maintaining a constant angle – while the others remained flexible (see Figure 3). I discovered that no matter how complex the system, and regardless of how many points could be flexible, if the well-chosen points were rigid, the number of possible movements was significantly reduced. These spaces allowed for only very limited and controlled motion.

Figure 3a, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

Figure 3b, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

Just as the interplay between rigid and flexible materials in my physical models determines the space’s adaptability, the balance between structure and agency in game design shapes the experiential and emotional depth of play.

In our era of gamification, designed game structures permeate every aspect of life – not only in traditional games but also in education, work, and everyday interactions.11 This widespread integration makes it essential to reflect on the ethical and aesthetic implications of game structure design.

In my view, the structure of a game plays a crucial role in determining how effectively it fosters meaningful engagement. Some designed structures encourage creativity, exploration, and intrinsic motivation, while others, through the excessive use of external reinforcers – such as points, awards, likes, or badges – condition player behaviour in ways that can lead to compulsion and addiction.12 When these reinforcers are introduced into a play system, they influence not only the nature of interactions but also the player's perception of success and failure. If such reinforcers dominate the structure, they risk diminishing the intrinsic value of play, reducing it to a conditioned response rather than an autonomous experience.

The artwork in contemporary cultural context

In most of my spatial experiments, the structures consist of connections between nodes (points) and segments (lines) that are flexible, capable of bending in any direction, and thus inherently unstable. The direction and quality of their movement are determined solely by the surrounding arrangement of points and lines (see Figures 1, 2, and 3).

Figure 1a, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

Figure 1b, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

For the final object, it was crucial that the movement of each node – independent of any surrounding structure – remained concrete and well-defined. The nodes are made of iron, and their interconnection and disassembly are facilitated by magnets. These nodes can rotate infinitely perpendicular to their axis at their meeting points, allowing the same set of components to be used for constructing either rigid or dynamic spaces.

Figure 2a, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

Figure 2b, Traces of responsibility in pre-designed structures, 2023, by Veronika Szalai.

This highlights the responsibility of the designer, as the same set of nodes can be assembled into a completely static structure with minimal movement or one that allows for a high degree of free motion. The design choices made in structuring these spaces directly influence the range of possible interactions, emphasizing the role of the designer in shaping the dynamics of movement and play within the system.

Sculptural Alignment and Ludic Conceptualism

In form, my physical object aligns with the twentieth and twenty-first-century sculptural concepts that emphasize the significance of negative space and trajectory in space formation.13 From a critical and experimental perspective, it resonates with ludic conceptualism. This genre, where Huizinga’s cultural theory of play served as a crucial reference point, was a blend of ludic art and social criticism that overlapped with the conceptual art movement in the Netherlands between 1959 and 1975.14 During this period, Huizinga’s Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element of Culture became an intellectual cornerstone for artists whose works prominently featured the element of play.

Case study: Bewogen Beweging

One notable example of ludic conceptualism is the exhibition Bewogen Beweging (Moved Movement), which showcased nearly two hundred works by more than seventy artists from the United States and Europe. These pieces, many of which moved or explored the concept of movement, constituted a survey of kinetic art. The exhibition offered visitors an unconventional experience with rusty wheels, chains, broken typewriters, strollers, and alarm clocks that not only moved but also made noises.

Bewogen Beweging served as a forum to question the uncritical embrace of machines. The artists’ playful critique was evident in the irrational movements of mechanical components, suggesting that play could serve as a serious response to, and critique of, the rapid industrialization and modernization that followed World War II in the Netherlands. Among the exhibits was Jean Tinguely's Cyclograveur, an anti-machine resembling a bicycle. Constructed from rusty parts scavenged from bicycles, cars, and baby carriages, this sculpture featured a saddle attached to a seat post twice the height of a typical bicycle. The pedals were connected to several gears and four wheels, with a large drawing board positioned about a metre in front. As participants pedalled, a hidden cogwheel moved an arm that drew on the board, while a bookstand in front of the handlebars allowed the player to read, diverting their attention away from the drawing process and letting the machine make the artistic decisions.15

The physical model as an expression of responsibility

My final object explores the responsibility inherent in play structure design, demonstrating how the same fundamental nodes or components can be arranged to create structures ranging from rigid and immovable to those that allow varying degrees of interaction and movement. This variability raises key questions: how much freedom should a structure afford, and what are the ethical implications of these choices?

In my artistic interpretation, the play state takes shape through a system of nodes and interconnections, embodying the delicate balance between stability and flexibility. This tension between constraint and agency underscores the designer’s critical role in shaping not only individual play experiences but also the broader cultural structures that define interaction and engagement.

The power of play lies not only in its ability to immerse and transform the individual, but also in its potential to reimagine and reconfigure the structures that define our collective existence.

Considering Huizinga’s cultural context and the message of ludic conceptualism, it becomes clear that this responsibility does not rest solely with the designer; rather, it is a collective cultural responsibility. The incentive values introduced by designers – or the secondary reinforcers shaped by cultural influences, such as money, grades, or social status – can, through learning and repetition, disrupt the intrinsic motivations of the player, sometimes in ways that undermine individual well-being and the sustainability of society as a whole.

Therefore, I argue that each of us holds both the responsibility and the potential to shape the cultural framework we share. By acknowledging this shared responsibility, we can strive to create play environments that foster empowerment, well-being, and meaningful engagement, rather than systems that prioritize control, obsession, or exploitation. In this sense, play is not merely a private or aesthetic experience but a cultural act – one that both reflects and actively shapes the values of our time. The power of play lies not only in its ability to immerse and transform the individual, but also in its potential to reimagine and reconfigure the structures that define our collective existence.

+++

Thesis supervisors: Anikó Illés, Pál Koós

Contribution by peer reviewers: Evert Hoogendoorn, Geert Belpaeme, and Willem-Jan Renger

Veronika Szalai

is a practice-based researcher, designer, and educator based in Hungary. She was awarded a doctorate in art and design from Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME, Budapest) in 2023. Her research focuses on play-based activities, which she integrates into both her independent work and teaching methods.

Noten

- Ego, self. ↩

-

This distinction between play and other activities, as described by Mérei and V. Binét, highlights the presence of a specific mental state – often referred to as “play consciousness,” – which aligns with my conceptualisation of the play state as an abstract field within the player's consciousness.

"For children, everything can be play, but not everything is. Moreover, behaviour that is identical in form and gesture may sometimes be play and at other times purposeful, problem-solving activity. What most clearly distinguishes play from many other activities of children is the joy inherent in it. Children exhibit a specific play behaviour that can be observed and recorded, and from a certain stage of development onward, it is assumed to have a distinct mental counterpart (play consciousness). A child at play is generally serene and relaxed (even amid the tensions of play), free from worry (though not from effort), and their activity is grounded in the present; even in multi-phase, goal-oriented play, it is characterised by the moment-to-moment joy of experience.”

Mérei, Ferenc, and Ágnes V. Binét. Gyermeklélektan. 6th ed., Gondolat, 1985, pp. 122-23. Translated by the author. ↩ - Vadeboncoeur, Jennifer A., and Artin Göncü. Playing and Imagining across the Life Course: A Sociocultural Perspective. The Cambridge Handbook of Play: Developmental and Disciplinary Perspectives, ed. by Peter K. Smith and Jaipaul L. Roopnarine, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 258-72. ↩

- Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element of Culture. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949, p. 2. ↩

-

Several foundational scholars have examined play as a broad phenomenon encompassing diverse human behaviours. Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens established play as a fundamental cultural force. Roger Caillois interprets many social structures as complex extensions of games, framing a wide range of joyful human behaviours as forms of play. Brian Sutton-Smith explores the inherent ambiguity of play, and Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s flow theory connects play to optimal experiences. Additionally, Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci’s self-determination theory addresses motivation in play, while Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman analyse play within the context of game design. These perspectives collectively reinforce the conceptual framework in which play is understood as a multidimensional phenomenon.

Caillois, Roger. Man, Play and Games. Translated by Meyer Barash, University of Illinois Press, 2001;

Csíkszentmihályi, Mihály. Flow – Az áramlat: A tökéletes élmény pszichológiája. Translated by Legéndyné Szilágyi Erzsébet, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1997;

Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. The Guilford Press, 2017;

Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. MIT Press, 2004;

Sutton-Smith, Brian. The Ambiguity of Play. Harvard University Press, 1997. ↩ - Fox, Lorna Scott, quoted in Alÿs, Francis. Children’s Game #23: Step on a Crack. 2020, francisalys.com/childrens-game-23-step-on-a-crack. Accessed 11 Dec. 2024. ↩

- Alÿs, Children’s Game #23. ↩

- Upton, Brian. The Aesthetic of Play. MIT Press, 2015, p. 286. ↩

- Mylopoulos, Myrto, and Elisabeth Pacherie. “Intentions: The dynamic hierarchical model revisited.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science, vol. 10, no. 2, 2019 (e1481). ↩

- Fredrickson, Barbara L., et al. Atkinson & Hilgard’s Introduction to Psychology. Cengage Learning, 2009. ↩

- Jagoda, Patrick. Experimental Games: Critique, Play, and Design in the Age of Gamification. University of Chicago Press, 2020. ↩

- Kapitány-Fövény, Máté. Ezerarcú függőség: Felismerés és felépülés. HVG Könyvek, 2019, pp. 37-41. ↩

-

Chau, Clement. Movement, Time, Technology, and Art. Springer Nature, 2017;

Weibel, Peter. Negative Space: Trajectories of Sculpture in the 20th and 21st Centuries. MIT Press, 2021. ↩ - Schoenberger, Thomas J. Ludic Conceptualism: Art and Play in the Netherlands, 1959 to 1975. CUNY Academic Works, 2017. ↩

- Schoenberger, pp. 98-102. ↩