This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 28 no. 1, pp. 48-57

A ritual of openness. The (meta-)reality of Anthony Braxton's Ghost Trance Music

Kobe Van Cauwenberghe

This article zooms in on the Ghost Trance Music compositions by the American composer Anthony Braxton. Simultaneously, it gives a broader perspective on Braxton’s oeuvre as a whole, as well as offering critical observations on the canon of post-war western art music.

Dit artikel neemt de Ghost Trance Music-composities van de Amerikaanse componist Anthony Braxton onder de loep. Het geeft tegelijkertijd een bredere kijk op Braxtons oeuvre als geheel en plaatst enkele kritische kanttekeningen bij de canon van naoorlogse westerse kunstmuziek.

Introduction: A Tri-Centric Thought Unit Construct

Over the past five decades, the American composer Anthony Braxton (1945) has written a body of work that is not only unprecedented in terms of scope, but also in terms of originality within the repertoire of post-war Western art music. His quality as a creator especially stands out due to the way in which composition and improvisation are interwoven in his work. In addition, he developed an extensive philosophical body of thought, which he describes in the three volumes of his Tri-Axium Writings, and published detailed analyses of his compositions in the five-volume Composition Notes. Braxton considers this complete oeuvre a holistic entity or construction in which everything is interconnected: a Tri-Centric Thought Unit Construct. This is not a stable construction but one that is continuously evolving; an imaginary world in constant motion. Braxton’s Tri-Centric Thought Unit Construct can be seen as one big open work. This article aims to highlight certain unique aspects of Braxton’s oeuvre and concurrently, critically examine the historical canon of post-war Western art music by focusing on what became the foundation of Braxton’s Construct: the Ghost Trance Musics.

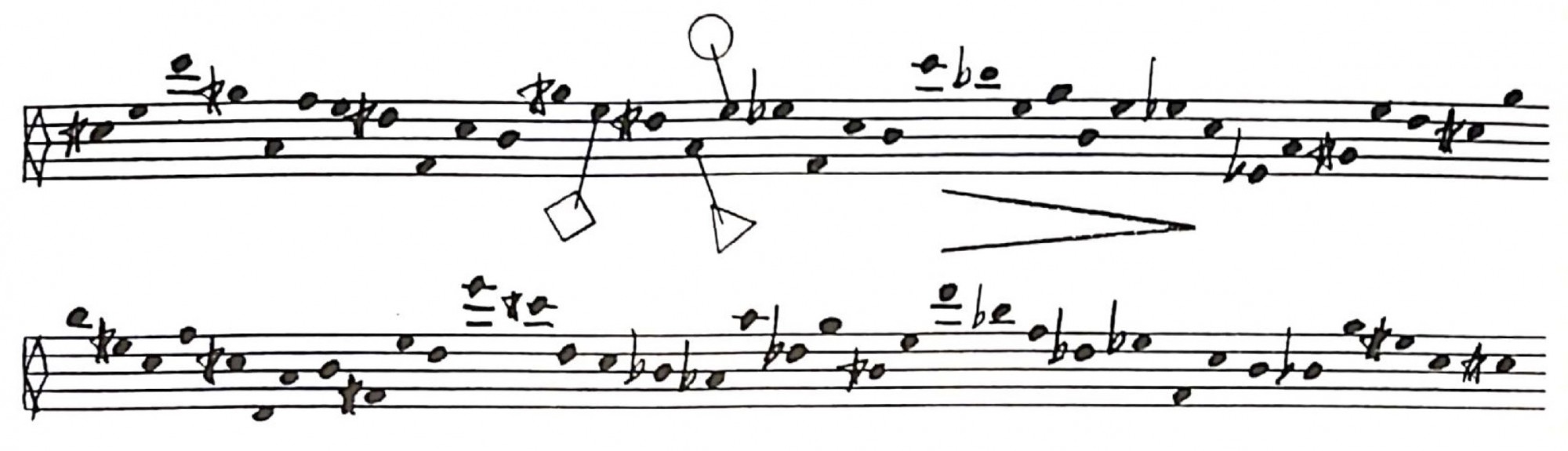

Fig. 1: Language Music © Anthony Braxton, courtesy of Tri-Centric Foundation

Ghost Trance Music (GTM) allowed Braxton to develop a composition system that unified his holistic oeuvre in a structural way. The more than one hundred and fifty GTM compositions, written between 1995 and 2006, form a significant part of his repertoire. In this article, I discuss GTM's architectural structure, its ritual and ceremonial meaning and its impact on performance practice. I will also diverge from my main subject in three places, analogous to the structure of GTM itself, in which the performer can deviate from the main melody at given moments symbolized by a circle, a square and a triangle. I will explore the role of improvisation in Braxton’s music (circle, mutable logics), give a bird's eye view on his complete Catalog of Work (square, stable logics) and finally make a connection with an existing discourse on the concept of the open work in post-war Western art music (triangle, correspondence logics).

Primary melody 1: A musical superhighway

There are several ways to approach Braxton’s GTM. The most accessible method is to consider its architectural dimension. Braxton describes GTM as an erector set in which the performers can shape the musical material themselves. The basic structure is simple. All GTM compositions consist of a single written melody: the primary melody, as well as so-called secondary material: three to four short trio compositions located at the back of the score. Concretely, a GTM performance starts from the primary melody, which is played in unison and at a constant pulse. In different places, the performer can then choose to deviate from the primary melody indicated by three symbols: a circle, a triangle or a square. Following the circle allows the performer to start improvising. The triangle provides the performer with the option to suddenly jump to the secondary material. The square refers to the tertiary material, allowing the performer to integrate any external composition or part from Braxton’s entire Catalog of Works into the performance. The primary melody can be picked up again at any time and runs like a central track throughout the performance.

In her illuminating article on GTM, Erica Dicker describes it as ‘a musical super-highway – a META-ROAD – designed to put the player in the driver's seat, drawing his or her intentions into the navigation of the performance, determining the structure of the performance itself’.1 GTM can be seen as a tool that allows performers to collectively and individually navigate their way through Braxton’s musical universe. Notation and improvisation flow intuitively and seamlessly into one another and various older or newer compositions from Braxton’s oeuvre can be integrated into the performance. Depending on the choices of the performer, this basic formation can quickly turn into a complex structure of musical layers each developing simultaneously. For Braxton, this aspect is linked to the underlying ceremonial and ritual meaning of GTM. Before going into that, we will first look at the role of improvisation in Braxton’s music.

Mutable logics: Language music and improvisation

Like many of his contemporaries, Braxton came into contact with free forms of improvisation in the 1960s. Entirely on-trend with that period and in tune with the civil rights movement, the idea of freedom increasingly gained importance, also within music. But as a musician, Braxton soon stumbled upon what he felt was a major limitation in total freedom in music. In an interview with Graham Lock he said the following:

So-called freedom has not helped us as a family, as a collective to understand responsibility better (...) so the notion of freedom that was being perpetrated in the sixties might not have been the healthiest notion. (…) I'm not opposed to the state of freedom (…) but fixed and open variables, with the fixed variables functioning from fundamental value systems – that's what freedom means to me.2

The balance between fixed and open variables has remained a constant in Braxton’s composition work. To find the right balance between structure and freedom, Braxton developed his Language Music system. This is a list of twelve specific sound parameters that he used as a kind of post-serial parametric framework to structure improvisations or shape compositions (see fig. 1). Initially, Braxton applied this to his Solo books, of which the double LP For Alto from 1969 is the best-known example. But soon, this seemingly simple list of twelve language types grew to become the DNA of Braxton’s music with a much wider range of associations. The list formed the basis of his holistic model in which each language type is associated with one of the twelve imaginary floors of the Tri-Centric Thought Unit Construct and, in turn, with the different musical systems Braxton developed over the years. Even the twelve main characters from Braxton’s Trillium operas are each associated with a specific language type. For example, GTM consists of long sounds and is part of the first floor; thus corresponds to the character Shala in Trillium (see fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Simplified view of the first three floors of Braxtons Tri-Centric Thought Unit Construct.

Braxton’s use of improvisation also reveals a historical tension when we place his work within the broad musical context of the second half of the twentieth century. There is a clear line that connects Braxton’s use of fixed and open variables with Charlie Parker’s bebop on the one hand, and with the work of experimental composers like John Cage (to whom Braxton dedicated one of the works on For Alto) on the other hand.3 At first, it may seem illogical to draw a line connecting Parker and Cage. However, in his essay Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives, composer George E. Lewis argues that this is in fact historically justifiable. He quotes from Braxton’s Tri-Axium Writings to clarify the issue: ‘Both aleatory and indeterminism are words which have been coined (...) to bypass the word improvisation and as such the influence of non-white sensibility’.4

Lewis suggests a direct link between the innovations of bebop, which developed in New York City in the 1940s, and the integration of open and free elements in the works of composers from the New York School some eight to ten years later (John Cage, Morton Feldman, Earl Brown, ...). The latter, however, clearly placed their work within a Eurocentric tradition of Western art music. Lewis argues that these composers consciously or unconsciously set themselves off against the radical developments within black American music of the 1940s and 1950s in order to be able to justify the reintegration of spontaneity and freedom in their compositions within a Eurological perspective.5 Following Lewis’s argument, I would suggest that the impact of this can still be seen in the prevailing perception of the works of a composer like Braxton. The innovations in his work, more specifically around compositional structure and its relation to improvisation and notions of freedom, are still often misrepresented and invariably fall outside the dominant paradigms of post-war Western art music.

Primary melody 2: The Ghost Dance

In the early ’90s, Anthony Braxton attended several classes on Native American music at Wesleyan University, where he taught. More specifically, the classes centred on a post-colonial ritual of the late nineteenth century called Ghost Dance, in which different indigenous tribes came together to make contact with their eradicated ancestors in hour-long circle dances or Ghost Dances. These experiences had a great impact on Braxton and were an important inspiration for what would become Ghost Trance Music. According to Dicker:

The Ghost Dance ritual provided Braxton with a vital structural model and affirmed his own ideas regarding human interconnection and ritual practices. GTM emulates the ceremonial and social aspects of the Ghost Dance and serves two purposes. The first is transcendental: GTM parts the curtain between Braxton’s past and current work, unifying it in the same “time-space.” GTM is also an arena in which Braxton helps curate intuitive experiences for both performers and listeners.6

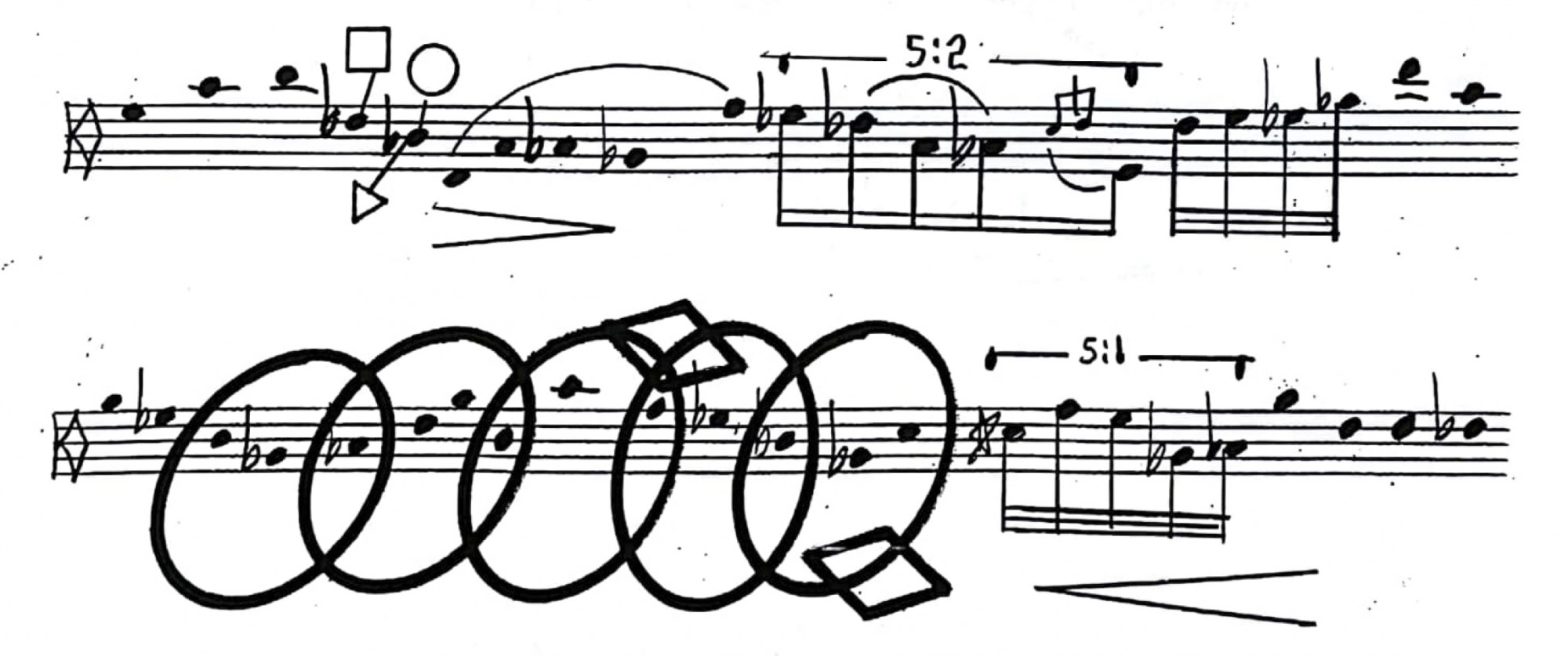

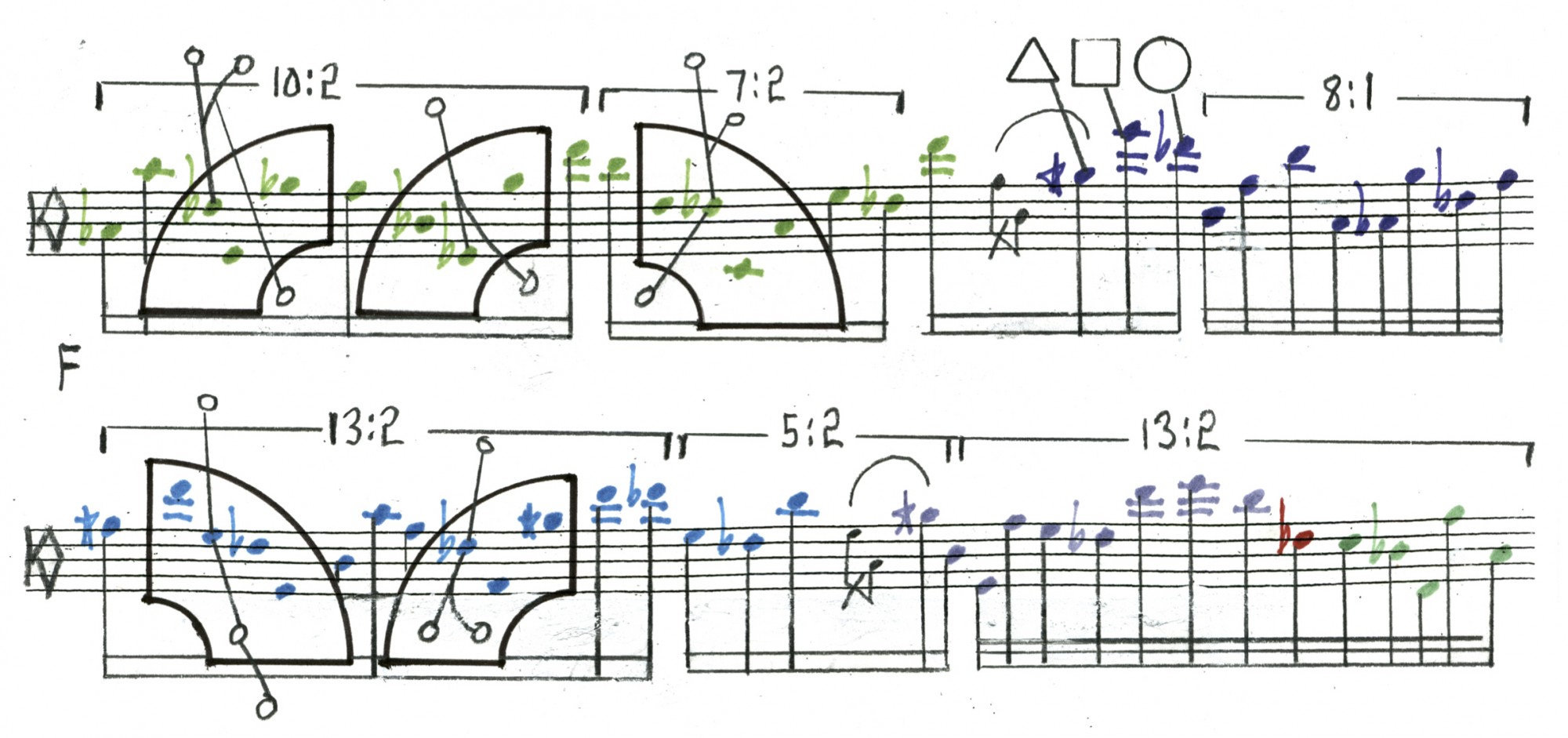

These ritual aspects form a vital part of GTM. They appear in their most literal form in the primary melody of early GTM compositions, also called first species GTM (1995-1998). Here, the primary melody consists of a continuous series of notes without any rhythmic variation. The melody is played in unison within a regular pulse resembling a trance beat, that seemingly continues without end. Braxton quickly started to expand on these first GTM compositions and developed additional types or species of GTM. In second species GTM (1998-2001), he introduced small rhythmic interruptions in the primary melody, which he then extended to complex rhythmic variations in third species GTM (2001-2004). The regular pulse increasingly disappeared into the background and additional graphic elements were introduced in the score. This culminated in Accelerator Whip GTM (2004-2006), in which the rhythmic complexity took on extreme forms, graphic interruptions became more elaborate and an additional colour code was introduced in the primary melody (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3a: First Species GTM (No. 193) © Anthony Braxton, courtesy of Tri-Centric Foundation

Even though the reference to trance music in these later GTM compositions is less obviously audible in the primary melody itself, the ritual and ceremonial aspect remains an essential part. Unlike a traditional 32-bar melody, the primary melody in GTM is continuous without a clear beginning or end. It is a melody that does not provide a structural hold, but rather functions as a starting point or tool for the performers to make their own choices.7 In order to use the primary melody as a tool, it is important for the performer to correctly understand the role of notation in Braxton’s work. In his Tri-Axium Writings, Braxton argued that notation has a different function in black creative music than in Western classical music. It is not only a means to create an exact reproduction of a musical work, but it also has a ‘ritual consideration’. According to Braxton, notation can be a stable factor that bridges the gap between the present and the past, and can also be a generating factor for developing new material.8

In the context of GTM, Braxton’s use of notation has a ‘ritual consideration’, so a loss of meaning occurs when spending hours practicing the complex rhythmic passages in, for example, Accelerator Whip GTM compositions. In Braxton’s music, interpretation always takes precedence over precision; by which he encourages the importance of agency within the performer. In other words, the notated music is never separate from improvisation and intuition. It is about how one, as a performer, both as an individual and as a collective, approaches and handles the material. I will explain the practical implications further on, but first, we will take a broader view of Braxton’s oeuvre as a whole.

Stable logics: Tertiary material

In order to provide a broader historical context on GTM and simultaneously present a clearer picture on Braxton’s ambitions as a composer, it makes sense to take a bird’s eye view on his extensive oeuvre. It is not my intention to give a complete overview, but to highlight some specific parts that occupy a central place in his Catalog of Works.9

In Braxton’s music, interpretation always takes precedence over precision; by which he encourages the importance of agency within the performer. In other words, the notated music is never separate from improvisation and intuition.

As mentioned earlier, Braxton developed his system of Language Music in the sixties as a basis for composing his various Solo books. In addition, Braxton’s various Collections of short compositions for the creative ensemble, often referred to as the Quartet books, also occupy a prominent place in his oeuvre. These compositions formed the basic repertoire of the various quartet formations with which he toured regularly until the early ’90s. Both the Solo and Quartet books were important experimental platforms for Braxton to develop and immediately put into practice his different music systems.

As early as the 1960s, Braxton experimented with various repetitive systems that he applied in his solos and quartet formations. Contrary to the strict minimalism of composers such as Glass and Reich, with whom Braxton was familiar, various improvisational elements were applied in his repetitive structures. An example of this are the so-called Kelvin compositions in which a short rhythmic melody is repeated, but the pitches can be improvised (compositions 6F, 40O, ...). From the ’70s, Braxton and his quartet had started to connect the different compositions by means of improvisations in long continuous suites; a way of working that he called co-ordinate music. In the ’80s, he went a step further in allowing different compositions to be played simultaneously, a process he titled collage music. For this, he developed his pulse track compositions, which were specifically written to be added as an extra layer to an existing composition.

Fig. 3b: Second Species GTM (No. 246) © Anthony Braxton, courtesy of Tri-Centric Foundation

In his 1988 essay Introduction to Catalog of Works, Braxton declared all his compositions to be connected to each other and considered them part of a larger whole. Concretely, he stated that all his compositions can be performed simultaneously, or that parts of existing compositions are permitted to be integrated within another host composition. The individual parts are autonomous and may be performed by any instrument or ensemble. Also, all tempi and dynamic markings are relative and adjustable by the performer according to the context.10

During the mid-’90s, Braxton suddenly came up with a whole new system: Ghost Trance Music. Although initially seen as a radical break from his quartet period, it is a logical evolution within Braxton’s philosophy of a holistic body of work. GTM is the system that converts his ideas into practice and allows the necessary connections to realize the unification of his oeuvre. Braxton wrote his last GTM compositions in 2006, but has since then developed several other systems that approach this process of unification in different ways, such as Falling River Music, Diamond Curtain Wall Music, Echo Echo Mirror House Music and ZIM Music. These works are each associated with a specific Language Type and are thus given a specific place within Braxton’s Tri-Centric Though Unit Construct (see fig. 2).

The innovations in his work, more specifically around compositional structure and its relation to improvisation and notions of freedom, are still often misrepresented and invariably fall outside the dominant paradigms of post-war Western art music.

Like many of his African American contemporaries, Braxton could rarely rely on institutional support from the government, universities, or private foundations for his compositional work throughout his career. Although he always avoided the term ‘jazz’ to describe his music, he was forced to realize his work on the jazz circuit and in the commercial sector.11 Consequently, an often overlooked part of Braxton’s Catalog of Works are his large-scale works. The best-known examples are Composition No. 19 for one hundred tubas and Composition No. 82 for four orchestras. Braxton’s most ambitious project is the Trillium opera cycle, consisting of 36 single acts that can be bundled into twelve operas. Braxton has been working continuously on Trillium since the 1980s. This enormous work in progress incorporates almost all elements of his Tri-Centric system: they are the culmination of his Ritual and Ceremonial Musics, his philosophical concepts from the Tri-Axium Writings are interwoven in the libretto and, as previously mentioned, the twelve main characters are each linked to one of the twelve stages of the Language Music system.

Although the influence of European composers such as Stockhausen and, in the case of Trillium, Wagner is clearly present in these large-scale works, another reality also plays a paramount function. In her dissertation on Trillium, Katherine Young points to the role of a ‘politics of scale’ in Braxton’s work. The large scale of these works not only generate more volume, but also more noise:

(...) the historical-social context in which the music—the physical sonic power, the noise—is produced does matter. Or, more specific to Braxton’s Trillium opera complex, the volume of sound produced by a Black American opera composer matters. Certainly, the radical, disruptive force that the noise (“screaming, wailing, honking, repetition, and so forth”) of 1960s free jazz imparted to Black radical politics mattered. (…) Thus, Braxton’s politics of scale, his politics of volume and noise, emerges in relation to the music of Black American radicals.12

Braxton’s final goal for the Trillium cycle is a twelve-day festival for world culture, in which each day a different part of the cycle is performed. To better understand Braxton’s motivation for these large-scale projects, Young refers to Graham Lock, who, in his book Bluetopia, links Braxton’s seemingly impossible ambitions to a well-known quote from Sun Ra: ‘The impossible attracts me because everything possible has been done and the world didn't change’.13

Primary melody 3: A transidiomatic and multihierarchic performance practice

Braxton never described his music as a rejection of existing traditions or styles. His Tri-Centric model never fixes itself on one specific musical idiom but is instead open to a plurality of musical practices. Trans-idiomatic is the term Braxton uses in this context. With GTM, Braxton created a musical arena or event-space within which such a trans-idiomatic performance practice can be fully explored. In other words, GTM is a unique platform for musicians to come together from a variety of backgrounds; where each individual's input determines the course and the common experience of the performance.

Another term Braxton regularly uses is multi-hierarchical, which refers to how decisions in his music can always be made on different levels, undermining the traditional hierarchy between composer, score, conductor and performer. With GTM, this becomes very apparent. There is usually one leader who indicates a limited number of general cues to the group as a whole. In addition, several subgroups can be assigned to make their own decisions. For example, they may choose to play one of the secondary or tertiary compositions or diverge to Language Music improvisation. Each performer is also free to make their own choices on an individual level. In this sense, a performer has complete liberty to stray from (or return to) the primary melody.14 The traditional division between soloist and accompaniment consequently disappears, allowing for a multi-hierarchical situation that Braxton describes as having ‘different fields of activities’.

Obviously, there is no unequivocal way to approach Braxton’s GTM repertoire and, by extension, his entire catalogue as a performer. What follows is a description of my personal experience as a performer of Braxton’s GTM and how I actualized the multi-hierarchical and trans-idiomatic performance practice. While the experiences were executed both in the context of a solo project and in a collective environment within a group of seven musicians, this is by no means a definitive description of how GTM should be played, but rather an illustration of how a possible performance of GTM can be executed.

Fig. 3c: Third Species GTM (No. 284) © Anthony Braxton, courtesy of Tri-Centric Foundation

To emphasize the trans-idiomatic aspect, I decided to work with a mixed group of musicians, some with a background in (contemporary) classical music and others specialized in jazz and improvised music.15 We performed Composition 284, a third species GTM composition. I divided the group into several trios and duos and assigned each subgroup with a selection of secondary and tertiary compositions. My role as leader in the project was limited to giving general cues indicating start and end of the concert, and to regroup at specific places on the primary melody during the performance. All subgroups and individual musicians are permitted to decide for themselves whether and when to introduce their assigned secondary and/or tertiary material. Furthermore, the many improvised passages based on Language Music also facilitated the creation of new ad hoc subgroups. Concretely, all musicians started each performance on the primary melody of Composition 284 together, but quite swiftly, the individual players or subgroups diverged towards their own musical path one by one, following the circle, triangle or square. All individuals in the group were free to familiarize themselves with the complex material through his or her personal background, and to adjust the music on different levels during the performance. This pluralistic approach ensured that Braxton’s open compositions were never given a uniform musical interpretation, which translated into a constantly evolving organic and dynamic interplay, allowing the group to work their way through the meta-road of Braxton’s musical universe.16

A trans-idiomatic and multi-hierarchical performance practice in a solo setting seems somewhat contradictory. Initially, it was not my intention to make a solo GTM version, but when I experimented with some of Braxton’s scores and used a looping device to simulate the multi-layered aspects of a group performance, I noticed that a version of a multi-hierarchical situation arose. By occasionally looping the guitar while playing, I would easily lose control over the loops, which would then influence my live playing. Instead of regaining control over the loops, I decided to push much further into the complexity of this situation. I added an extra looping device allowing for two separate layers of live-recorded material during a performance. I also pre-recorded parts of the secondary and tertiary compositions to use as samples to which I applied electronic effects with randomized parameters, rendering the overall sound result even more unpredictable. Because of the possibility to generate broad layering prospects by using loops, samples and electronics, I was also able to switch between different instruments (electric, acoustic and bass guitar) and add varying registers and timbres as well. The trans-idiomatic element in these Ghost Trance Solos is subtler and underlines the lack of reliability of the performers’ experienced knowledge, pushing and encouraging them to constantly step out of their comfort zone, to constantly question and reinvent themselves in a sort of musical soliloquy.17

Correspondence logics: Secondary material

To conclude, we follow the triangle leading us to the secondary material in the GTM score, which Braxton associates with synthesis or correspondence logics. Here, I ask myself the question: how does Braxton’s work correspond to other existing examples of open works in the post-war canon of Western art music?

First coined in 1959 in his essay Poetics of the Open Work, writer and philosopher Umberto Eco used the term open work to describe compositions that incorporated open elements, and in which the performer is allowed to make his or her own choices when performing. In this essay, Eco examines how works of art often reflect the world view of their time. He illustrates this by making a connection between the use of open elements in the work of composers such as Luciano Berio, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henri Pousseur and Pierre Boulez and evolutions in science at the time, such as Einstein’s theory of relativity and quantum physics.18

Even more vocal about open elements was composer John Cage, who made the term indeterminacy commonplace in recent music history. However, unlike Eco’s associations with developments in science, Cage was inspired by Zen Buddhism for his understanding of indeterminacy in a musical context. In his influential book Silence, he formulated a broad and inclusive definition for experimental music as ‘an experimental action the outcome of which is not foreseen [and is] necessarily unique’. Although Cage’s definition of experimental music implies a wide range of potential practices, he was openly averse to the developments in (free-)jazz, which he openly addressed in the controversial quote stating: ‘[j]azz per se derives from serious music. And when serious music derives from it, the situation becomes rather silly’.19

Fig. 3d: Accelerator Whip GTM (No. 358) © Anthony Braxton, courtesy of Tri-Centric Foundation

Returning to the aforementioned essay by George Lewis Improvisation after 1950, it is difficult to ignore how both Eco and Cage approached their subject from a strictly Eurological perspective. By linking their vision of openness in music to either a scientific or Zen-inspired discourse, they both created an intellectual framework that could be called a space of whiteness in the context of Lewis’s essay.20 Braxton considered and noted how non-white sensibilities were rarely taken into account in this kind of discourse; a typical example of stereotyping, which he described in his Tri-Axium Writings as ‘the grand trade off’:

In this concept, black people are vibrationally viewed as being great tap dancers - natural improvisers, great rhythm, etc, etc, etc - but not great thinkers, or not capable of contributing to the dynamic wellspring of world information. White people under this viewpoint have come to be viewed as great thinkers, responsible for all of the profound philosophical and technological achievements that humanity has benefitted from - but somehow not as “natural” as those naturally talented black folks.21

In his book A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music, George Lewis paints a detailed picture of the complex reality in which many African American musicians found themselves in the New York scene of the 1960s. He describes two avant-garde movements that existed side by side: one was the predominantly white New York School and Fluxus scene that had access to a network of public and private foundations and academic positions in universities, and the other consisted of many black radical artists, such as Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra and numerous others, who were forced to create their work in jazz clubs and the commercial sector.22 Moreover, black musicians did not have the same referential freedom to experiment as their white colleagues.23

Braxton was confronted with this complex reality throughout his career. He only managed to realize a work like Composition 82 for four orchestras due to a record deal with the jazz label Arista. At the same time, the project marked the end of this contract and saddled him with years of debts. Braxton has openly quoted Cage and Stockhausen as being important influences on his work; an association that led to Braxton’s music being ironically labelled ‘too white’ by the (often white) jazz critics. Yet he was well aware of the problematic attitude of composers like Cage and Stockhausen towards African American music. Braxton says the following about this ambiguous relationship in a conversation with Mike Heffley:

It would have been very nice for me to just say fuck Stockhausen and Cage, it would have made my life easier, but that wasn’t the relationship I wanted to have with my discipline. Being open to it gives me a chance to reshape it to my own aesthetic based on whatever my needs are at the time.24

In this last sentence, Braxton gives a completely different dimension to the concept of open in a musical context. It is my conviction that Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music and, by extension, his entire Tri-Centric Thought Unit Construct can be seen as one of the many proverbial elephants in the room when we look at the still prevalent perception on the canon of post-war Western art music. Today, it is hard to deny that this perception is strongly determined by a constructed dichotomy that separates Western art music from evolutions and radical experiments in jazz and African American music. Braxton’s unique way of combining compositional structure with free and open forms is both embedded in a long tradition of African American music, as well as in the Eurological modernism of composers such as Cage and Stockhausen. It would dishonour an oeuvre like Braxton’s to want to place it within the existing historical paradigms, since these are simply too limited. A broadening or renewal of these paradigms, and subsequently the canon itself, seems to be necessary. According to George Lewis, this can already start with a small act of curation. In his recently published eponymous article, Lewis pleads for the creation of a new, creolized and usable past of new music.25 In other words, the construction of a useful musical past that does not only depart from Schoenberg’s ‘Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten’, but also from Sun Ra’s ‘There Are Other Worlds (They Have Not Told You Of)’.

+++

Kobe van Cauwenberghe

is a guitarist and dedicated performer of contemporary music and plays concerts all over the world. He is a researcher and PhD candidate at the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp, where he is currently conducting research on the music of American composer Anthony Braxton.

Footnotes

- Dicker, Erica. “Ghost Trance Music.” Sound American, vol. 16, archive.soundamerican.org/sa_archive/sa16/sa16-ghost-trance-music.html, last consulted 17 July 2020. ↩

- Lock, Graham. Forces In Motion: Anthony Braxton and the Meta-reality of Creative Music: Interviews and Tour Notes, England 1985. Quartet, 1988, p. 240. ↩

- Bebop developed in New York in the 1940s as a counterpart to the then popular Swing music and is characterized by long spun out improvised passages, faster tempi and a greater emphasis on rhythmic unpredictability and harmonic complexity. ↩

- Lewis, George, E. “Improvisation after 1950, Eurological vs Afrological perspectives.” Black Music Research Journal, vol. 22, 2002, p. 223. ↩

- ‘It is my contention that, circumstantially at least, bebop’s combination of spontaneity, structural radicalism, and uniqueness, antedating by several years the reappearance of improvisation in Eurological music, posed a challenge to that music which needed to be answered in some way. (…) In this regard, the ongoing Eurological critique of jazz may be seen as part of a collective project of reconstruction of a Eurological real-time musical discipline. This reconstruction may well have required the creation of an “other” – through reaction, however negative, to existing models of improvisative musicality (...)’ Lewis, “Improvisation after 1950.” p. 228. ↩

- Dicker, “Ghost Trance Music.” ↩

- Or, as Braxton puts it, ‘Rather than have a composition that goes from “Mary had a little lamb” and then it’s finished, it’s like “Mary had…” and then there’s a lot different things she could have had’ ↩

- ‘Notation as practiced in black improvised creativity (…) has been utilized as both a recall-factor as well as a generating factor to establish improvisational co-ordinates. In this context notation is utilized as a ritual consideration and (...) becomes a stabilizing factor that functions with the total scheme of the music rather than a dominant factor at the expense of the music'. Braxton, Anthony. Tri-Axium Writings vol.3, Frog Peak Music, 1985, pp. 35-36. ↩

- For a full overview of Braxton’s Catalog of Works, please refer to the website of the Tri-Centric Foundation: tricentricfoundation.org/scores. ↩

- Braxton, Anthony. “Introduction to Catalog of works.” Audio Culture, readings in modern music, red. Cristophe Cox, C. & Daniel Warner, Bloomsbury, 2004, p. 201-204. ↩

- ‘I still get treated like a jazz musician rather than a concert musician - like when I got my piece for five tubas recorded, it was only because we had signed the contracts and everything before; I was supposed to come in with my bass, drums and trumpet, and I slipped in with five tubas, (...) I’ve never had a record date of any of my written music, and so I’m represented for the most part as a saxophone player (…). But that’s a small part of what I do'. Smith, Bill. “Anthony Braxton Interview 1973” Bill Smith: Imagine The Sound, vancouverjazz.com/bsmith/2009/01/anthony-braxton-interview-1973.html, last consulted 26 October 2020. ↩

- Young, Katherine. Nothing As It Appears: Anthony Braxton’s Trillium J. Doctoral Thesis, North Western University, 2017, p. 15. ↩

- Lock, Graham. Blutopia: Visions of the Future and Revisions of the Past in the works of Duke Ellington, Sun Ra and Anthony Braxton. Duke University Press, 1999, p. 209. ↩

- In most of his scores, Braxton applies the use of a “diamond clef”, his alternative to traditional keys in which the performer is free to choose which key to play. Therefore, even before the first note is played, each individual is required to make a significant decision. ↩

- Teun Verbruggen (drums), Steven Delannoye (saxophone), Frederik Sakham (double bass), Niels Van Heertum (euphonium), Elisa Medinilla (piano), Anna Jalving (violin). ↩

- Here is an excerpt of a roughly recorded live concert in Antwerp on 07/02/2020: soundcloud.com/kobevc/ghost-trance-septet-plays-anthony-braxton-composition-285-excerpt. A double bill concert with Braxton himself was scheduled at Rainy Days Festival in Luxembourg in November 2020, but had to be cancelled due to the COVID19 crisis. ↩

- A studio recording of Ghost Trance Solos was released on the label All That Dust: allthatdust.com/releases/ghost-trance-solos. A live recording of a performance of Composition 285 at Articulate Research Days in October 2019 is available on soundcloud: soundcloud.com/kobevc/anthony-braxton-composition-285-40f-108a-304-40b-40o-69q. ↩

- ‘In this general intellectual atmosphere, the poetics of the open work is peculiarly relevant: it posits the work of art stripped of necessary and foreseeable conclusions, works in which the performer’s freedom function as part of the discontinuity which contemporary physics recognizes. (...) Thus the concepts of “openness” and dynamics may recall the terminology of quantum physics: indeterminacy and discontinuity'. Eco, Umberto. “Poetics of the Open Work.” Audio Culture, readings in modern music, red. Cristophe Cox, C. & Daniel Warner, Bloomsbury, 2004, p. 171. ↩

- Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Wesleyan University Press, 1961, p.72. ↩

- Lewis refers to John Fiske: ‘The space of whiteness contains a limited but varied set of normalizing positions from which that which is not white can be made into the abnormal; by such means whiteness constitutes itself as a universal set of norms by which to make sense of the world’. Lewis, p. 224. ↩

- Braxton, Anthony. Tri-Axium Writings vol.1. Frog Peak Music, 1985, p. 305. ↩

- ‘The sums expended were often breathtaking. For instance, between 1979 and 1983, the Dia Foundation poured $4 million into composer La Monte Young’s conceptual work, “Dream House.” In contrast, the “natural” home of the black musical avant-garde was presumed to be the jazz club and the commercial sector’. Lewis, George, E. A Power Stronger Than Itself: the AACM and American Experimental Music. The University of Chicago Press, 2009, p. 36. ↩

- ‘Here, black artists faced an especially frustrating conundrum. Even as a strong investment was being made in the positional and referential freedom of white artists, for black artists there was a concomitant assumption that either total Europeanization or a narrowly conceived, romanticized “Africanization” were the only options’. Lewis, p. 33. ↩

- Heffley, M. The Music of Anthony Braxton. Routledge, 1996. p. 130. ↩

- Lewis, George, E. “A Small Act of Curation.” On Curating, Issue 44, 2020. on-curating.org/issue-44-reader/a-small-act-of-curation.html#.XkpBfC3MzOR, last consulted 8 July 2020. ↩